Every accusation by a grubby Ziontologist is a confession.Maybe you should try it yourself sometime instead of just picking and choosing. When you pick and choose you are simply being a hypocrite and you render your profound proclamations hollow and worthless.

Oct.7 was a crime against humanity, a war crime. Say it.

Israel at war

- Thread starter Butler1000

- Start date

The HRW calls for investigations into Hamas for acts on Oct 7.You refuse to accept what the HRW says regarding Oct.7 How pathetically hypocritical.

I fully support that report, hold both sides to the equally.

Just as we should back this HRW call, as you obviously must support if you think HRW's work is trustworthy.

Guess the Hamas terrorists will never learn. Do they really think NATO won't get involved in this one?

I guess they became desperate after ongoing news of a Saudi/Israeli peace treaty became public. They are hoping for a response to curtail it.

Houthis Launch Deadly Drone Strike on Tel Aviv, Evading Israel’s Defenses

At least one person was killed and eight others injured in a predawn attack on Friday. The Israeli military said it was investigating why it “did not identify it, attack it and intercept it.”

Every post by you is ignorant hate speech.Every accusation by a grubby Ziontologist is a confession.

What is a Ziontologist? What does Shazi mean, microbe?

The racial supremacist again calls a critic 'subhuman'.Every post by you is ignorant hate speech.

What is a Ziontologist? What does Shazi mean, microbe?

Well done, Shazi.

Turf Israel from the olympics.

Boycott them until they respect international law and leave Palestine.

Keep bullshitting Geno.The HRW calls for investigations into Hamas for acts on Oct 7.

They already released the results of that investigation 3 days ago.

Hamas and other groups committed war crimes on 7 October - HRW (bbc.com)

You say they are trustworthy, then you agree when they say:Just as we should back this HRW call, as you obviously must support if you think HRW's work is trustworthy.

Hamas and at least four other Palestinian armed groups committed numerous war crimes and crimes against humanity against civilians during the 7 October attack on southern Israel, the campaign group Human Rights Watch says.

A new report accuses the hundreds of gunmen who breached the Gaza border fence of violations including deliberate and indiscriminate attacks on civilians, wilful killing of persons in custody, sexual and gender-based violence, hostage-taking, mutilation of bodies and looting.

It also found the killing of civilians and hostage-taking were “central aims of the planned attack” and not an “afterthought”.

Says the guy who calls Gazans and Palestinians "lesser humans." You make yourself look more and more ridiculous everyday. From January of this year:The racial supremacist again calls a critic 'subhuman'.

I think there is an exception for all chosen people, they can do no wrong and slaughtering lesser humans is part of their path of righteousness.

Idiotic. As if that will save even one Gazan life? BTW, are you talking about Olympics where the PLO kidnapped innocent Israeli athletes and savagely killed them in cold blood? For that reason alone, Israel will never be banned from the Olympics.Turf Israel from the olympics.

Boycott them until they respect international law and leave Palestine.

If you actually gave an iota of care for the Gazans, you'd call for a Hamas surrender. It's inevitable they'll be destroyed because not a single country is providing any troops to help Hamas and their shrinking army while more Gazans die as you wait 10 years for your boycotts. And the UN will not send in the military either while the ICJ rulings are not binding.

You continue to cheer for Hamas' incestuous genocide of their own people. This is the worst crime in history. Hamas have a hand in every single death that's occured in Gaza. Seeing as the authors of that opinion letter to the editor of Lancet did not attribute blame to Israel, it must be Hamas.

A MESSAGE FROM THE NEW PRESIDENT OF IRANThe racial supremacist again calls a critic 'subhuman'.

Well done, Shazi.

Turf Israel from the olympics.

Boycott them until they respect international law and leave Palestine.

As Bibi's visit to US Congress approaches, I expect the cacophony blaming Iran's malign intent to get shriller by the day. As a contrast, read President Pezeshkian's message and judge for yourself.

By Iranian President-elect Masoud Pezeshkian

My message to the new world

July 12, 2024 - 20:59

TEHRAN – On May 19, 2024, the untimely passing of President Ebrahim Raisi- a deeply respected and dedicated public servant- in a tragic helicopter crash precipitated early elections in Iran, marking a pivotal moment in our nation's history.

Amidst war and turbulence in our region, Iran’s political system demonstrated remarkable stability by conducting elections in a competitive, peaceful, and orderly manner, dispelling insinuations made by some “Iran experts” in certain governments. This stability, and the dignified manner in which the elections were conducted, underscore the discernment of our Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, and the dedication of our people to democratic transition of power even in the face of adversity.

I ran for office on a platform of reform, fostering national unity, and constructive engagement with the world, ultimately earning the trust of my compatriots at the ballot box, including those young women and men dissatisfied with the overall state of affairs. I deeply value their trust and am fully committed to cultivating consensus, both domestically and internationally, to uphold the promises I made during my campaign.

I wish to emphasize that my administration will be guided by the commitment to preserving Iran's national dignity and international stature under all circumstances. Iran’s foreign policy is founded on the principles of "dignity, wisdom, and prudence", with the formulation and execution of this state-policy being the responsibility of the president and the government. I intend to leverage all authority granted to my office to pursue this overarching objective.

With this in mind, my administration will pursue an opportunity-driven policy by creating balance in relations with all countries, consistent with our national interests, economic development, and requirements of regional and global peace and security. Accordingly, we will welcome sincere efforts to alleviate tensions and will reciprocate good-faith with good-faith.

Under my administration, we will prioritize strengthening relations with our neighbors. We will champion the establishment of a "strong region" rather than one where a single country pursues hegemony and dominance over the others. I firmly believe that neighboring and brotherly nations should not waste their valuable resources on erosive competitions, arms races, or the unwarranted containment of each other. Instead, we will aim to create an environment where our resources can be devoted to the progress and development of the region for the benefit of all.

We look forward to cooperating with Turkiye, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Iraq, Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, and regional organizations to deepen our economic ties, bolster trade relations, promote joint-venture investment, tackle common challenges, and move towards establishing a regional framework for dialogue, confidence building and development. Our region has been plagued for too long by war, sectarian conflicts, terrorism and extremism, drug trafficking, water scarcity, refugee crises, environmental degradation, and foreign interference. It is time to tackle these common challenges for the benefit of future generations. Cooperation for regional development and prosperity will be the guiding principle of our foreign policy.

As nations endowed with abundant resources and shared traditions rooted in peaceful Islamic teachings, we must unite and rely on the power of logic rather than the logic of power. By leveraging our normative influence, we can play a crucial role in the emerging post-polar global order by promoting peace, creating a calm environment conducive to sustainable development, fostering dialogue, and dispelling Islamophobia. Iran is prepared to play its fair share in this regard.

In 1979, following the Revolution, the newly established Islamic Republic of Iran, motivated by respect for international law and fundamental human rights, severed ties with two apartheid regimes, Israel and South Africa. Israel remains an apartheid regime to this day, now adding "genocide" to a record already marred by occupation, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, settlement-building, nuclear weapons possession, illegal annexation, and aggression against its neighbors.

As a first measure, my administration will urge our neighboring Arab countries to collaborate and utilize all political and diplomatic leverages to prioritize achieving a permanent ceasefire in Gaza aiming to stop the massacre and prevent the broadening of the conflict. We must then diligently work to end the prolonged occupation that has devastated the lives of four generations of Palestinians. In this context, I want to emphasize that all states have a binding duty under the 1948 Genocide Convention to take measures to prevent genocide; not to reward it through normalization of relations with the perpetrators.

Today, it seems that many young people in Western countries have recognized the validity of our decades-long stance on the Israeli regime. I would like to take this opportunity to tell this brave generation that we regard the allegations of antisemitism against Iran for its principled stance on the Palestinian issue as not only patently false but also as an insult to our culture, beliefs, and core values. Rest assured that these accusations are as absurd as the unjust claims of antisemitism directed at you while you protest on university campuses to defend the Palestinians' right to life.

China and Russia have consistently stood by us during challenging times. We deeply value this friendship. Our 25-year roadmap with China represents a significant milestone towards establishing a mutually beneficial "comprehensive strategic partnership," and we look forward to collaborating more extensively with Beijing as we advance towards a new global order. In 2023, China played a pivotal role in facilitating the normalization of our relations with Saudi Arabia, showcasing its constructive vision and forward-thinking approach to international affairs.

Russia is a valued strategic ally and neighbor to Iran and my administration will remain committed to expanding and enhancing our cooperation. We strive for peace for the people of Russia and Ukraine, and my government will stand prepared to actively support initiatives aimed at achieving this objective. I will continue to prioritize bilateral and multilateral cooperation with Russia, particularly within frameworks such as BRICS, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and Eurasia Economic Union.

Recognizing that the global landscape has evolved beyond traditional dynamics, my administration is committed to fostering mutually beneficial relations with emerging international players in the Global South, especially with African nations. We will strive to enhance our collaborative efforts and strengthen our partnerships for the mutual benefit of all involved.

Iran's relations with Latin America are well-established and will be closely maintained and deepened to foster development, dialogue and cooperation in all fields. There is significantly more potential for cooperation between Iran and the countries of Latin America than what is currently being realized, and we look forward to further strengthening our ties.

Iran’s relations with Europe have known its ups and downs. After the United States’ withdrawal from the JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action) in May 2018, European countries made eleven commitments to Iran to try to salvage the agreement and mitigate the impact of the United States’ unlawful and unilateral sanctions on our economy. These commitments involved ensuring effective banking transactions, effective protection of companies from U.S. sanctions, and the promotion of investments in Iran. European countries have reneged on all these commitments, yet unreasonably expect Iran to unilaterally fulfill all its obligations under the JCPOA.

Despite these missteps, I look forward to engaging in constructive dialogue with European countries to set our relations on the right path, based on principles of mutual respect and equal footing. European countries should realize that Iranians are a proud people whose rights and dignity can no longer be overlooked. There are numerous areas of cooperation that Iran and Europe can explore once European powers come to terms with this reality and set aside self-arrogated moral supremacy coupled with manufactured crises that have plagued our relations for so long. Opportunities for collaboration include economic and technological cooperation, energy security, transit routes, environment, as well as combating terrorism and drug trafficking, refugee crises, and other fields, all of which could be pursued to the benefit of our nations.

The United States also needs to recognize the reality and understand, once and for all, that Iran does not—and will not—respond to pressure. We entered the JCPOA in 2015 in good faith and fully met our obligations. But the United States unlawfully withdrew from the agreement motivated by purely domestic quarrels and vengeance, inflicting hundreds of billions of dollars in damage to our economy, and causing untold suffering, death and destruction on the Iranian people—particularly during the Covid pandemic—through the imposition of extraterritorial unilateral sanctions. The U.S. deliberately chose to escalate hostilities by waging not only an economic war against Iran but also engaging in state terrorism by assassinating General Qassem Soleimani, a global anti-terrorism hero known for his success in saving the people of our region from the scourge of ISIS and other ferocious terrorist groups. Today, the world is witnessing the harmful consequences of that choice.

The U.S. and its Western allies, not only missed a historic opportunity to reduce and manage tensions in the region and the world, but also seriously undermined the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) by showing that the costs of adhering to the tenets of the non-proliferation regime could outweigh the benefits it may offer. Indeed, the U.S. and its Western allies have abused the non-proliferation regime to fabricate a crisis regarding Iran's peaceful nuclear program - openly contradicting their own intelligence assessment - and use it to maintain sustained pressure on our people, while they have actively contributed to and continue to support the nuclear weapons of Israel, an apartheid regime, a compulsive aggressor and a non-NPT member and a known possessor of illegal nuclear arsenal.

I wish to emphasize that Iran’s defense doctrine does not include nuclear weapons and urge the United States to learn from past miscalculations and adjust its policy accordingly. Decision-makers in Washington need to recognize that a policy that consists of pitting regional countries against each other has not succeeded and will not succeed in the future. They need to come to terms with this reality and avoid exacerbating current tensions.

The Iranian people have entrusted me with a strong mandate to vigorously pursue constructive engagement on the international stage while insisting on our rights, our dignity and our deserved role in the region and the world. I extend an open invitation to those willing to join us in this historic endeavor.

Yup, HRW reported Israeli claims and said investigate and take them to trial.Keep bullshitting Geno.

They already released the results of that investigation 3 days ago.

Hamas and other groups committed war crimes on 7 October - HRW (bbc.com)

You say they are trustworthy, then you agree when they say:

Hamas and at least four other Palestinian armed groups committed numerous war crimes and crimes against humanity against civilians during the 7 October attack on southern Israel, the campaign group Human Rights Watch says.

A new report accuses the hundreds of gunmen who breached the Gaza border fence of violations including deliberate and indiscriminate attacks on civilians, wilful killing of persons in custody, sexual and gender-based violence, hostage-taking, mutilation of bodies and looting.

It also found the killing of civilians and hostage-taking were “central aims of the planned attack” and not an “afterthought”.

Same they said for Israel.

I'm glad to hear you trust HRW and think that investigations and charges should result from their reports on Israel and Hamas.

For once we agree.

(and congrats on figuring out to do large, blue fonts, next up, set the clock on your vcr)

I was talking about people who call themselves 'chosen people'. I didn't mention Palestinians, that was you jumping to your supremacist conclusions and confirming what I said about zionists is accurate. You read 'lesser humans' and immediately you thought Palestinians. Dead giveaway, Shazi.Says the guy who calls Gazans and Palestinians "lesser humans." You make yourself look more and more ridiculous everyday. From January of this year:

BDS, Shazi.Idiotic. As if that will save even one Gazan life? BTW, are you talking about Olympics where the PLO kidnapped innocent Israeli athletes and savagely killed them in cold blood? For that reason alone, Israel will never be banned from the Olympics.

If you actually gave an iota of care for the Gazans, you'd call for a Hamas surrender. It's inevitable they'll be destroyed because not a single country is providing any troops to help Hamas and their shrinking army while more Gazans die as you wait 10 years for your boycotts. And the UN will not send in the military either while the ICJ rulings are not binding.

You continue to cheer for Hamas' incestuous genocide of their own people. This is the worst crime in history. Hamas have a hand in every single death that's occured in Gaza. Seeing as the authors of that opinion letter to the editor of Lancet did not attribute blame to Israel, it must be Hamas.

Sanctions will end zionism without killing people.

I know you only think in terms of killing people and blowing things up, but that's not where real strength lies.

All that terrorist nation can do is start wars and kill people.

The Jews are known as the chosen people. You have said that all Jews in Israel are Zionists and you hate all Zionists. We were talking about the war in Gaza and you incessantly refer to it as genocide. It is laughable for you to try to deny that you were referring to the Gazans being slaughtered (in your words) by the IDF/Israelis/Jews/Zionists/Chosen people. They are all one and the same to you.I was talking about people who call themselves 'chosen people'. I didn't mention Palestinians, that was you jumping to your supremacist conclusions and confirming what I said about zionists is accurate. You read 'lesser humans' and immediately you thought Palestinians. Dead giveaway, Shazi.

You clearly referred to the Gazans as being lesser humans being slaughtered by Israel and there is no other interpretation. So for you to say " The racial supremacist again calls a critic 'subhuman'" is rich. You need to keep better track of your lies and insults, Geno. You're like a dog chasing its' tail.

You called Gazans "lesser humans", not I. Deny as much as you want, but everyone can see it in black and white. You can't weasel around it.

BDS has being going on for at least 5 years. How long are you willing to wait for them to work? In 9 months 38,000 dead. 3 more years is another 150,000 and you are evidently cool with that.BDS, Shazi.

Sanctions will end zionism without killing people.

This is proof that you don't care how many die. A Hamas surrender and release of hostages stops the war immediately. Instead, you are literally saying that you want more and more Gazans to die. Demonizing Israel is more important to you Gazan lives.

I know you only think in terms of killing people and blowing things up, but that's not where real strength lies.

All the Palestinians can do is use terror/violence as their number one export. Nobody wants them because they spread terror wherever they go. Not Jordan, not Egypt, not Yemen, not the Saudis, not UAE, not Qatar etc. Palestinians are the terrorists with no nation because they were too full of hate and violence to accept enough land to give them their own state in 1948.All that terrorist nation can do is start wars and kill people.

This is what HRW reported 3 days ago. Now that they've done so, what is your comment on this particular report.Yup, HRW reported Israeli claims and said investigate and take them to trial.

Same they said for Israel.

Hamas and other groups committed war crimes on 7 October - HRW (bbc.com)

Human Rights Watch report accuses Hamas, other militant groups of war crimes on Oct. 7 | CBC News

Hamas' War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity (HRW) (juancole.com)

Human Rights Watch Finds Hamas-Led Militants Committed War Crimes On Oct. 7 | HuffPost Latest News

October 7 Crimes Against Humanity, War Crimes by Hamas-led Groups | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org)

Hamas committed 'hundreds' of war crimes on October 7, HRW says - France 24

You are such a coward. You have no shame. Try being an honourable man for once, a mensch.

Last edited:

Nah, pretty much every religious wacko from every religion thinks they are the chosen people. How else you gonna talk people into that ponzi scheme of jehova's witnesses needing sales to buy one of the limited thousands of seats in the afterlife?The Jews are known as the chosen people.

Nope, I have never said that. Not once. Total hasbara troll lie that you repeat. Its a lie. Stop it. Its stupid.You have said that all Jews in Israel are Zionists and you hate all Zionists.

Its a genocide, not a war. The ICJ ruling states that Israel is the occupying power and you cannot declare war against people you are already occupying. The UN has also repeatedly stated its a genocide. So stop the lying. Stick to the legal definitions and internationally recognized views.We were talking about the war in Gaza and you incessantly refer to it as genocide.

No, I was making a sarcastic comment on how totally fucked up religious extremists are and you just proved you are a religious extremist by taking it as fact and instantly deciding that any reference to 'lesser humans' must be the people you are backing exterminating.It is laughable for you to try to deny that you were referring to the Gazans being slaughtered (in your words) by the IDF/Israelis/Jews/Zionists/Chosen people. They are all one and the same to you.

Nope, we've been over this repeatedly. I didn't refer to either zionists or Palestinians in that comment, just religious extremists who think they are the 'chosen people'. Being a religious extremist you just instantly jumped in and though it only applies to you, as all religious extremists don't recognize that all other religious extremists also think they are the 'chosen people'.You clearly referred to the Gazans as being lesser humans being slaughtered by Israel and there is no other interpretation. So for you to say " The racial supremacist again calls a critic 'subhuman'" is rich. You need to keep better track of your lies and insults, Geno. You're like a dog chasing its' tail.

No, I made no reference to Palestinians. There is no such thing as 'Gazans', they are Palestinians, by the way.You called Gazans "lesser humans", not I. Deny as much as you want, but everyone can see it in black and white. You can't weasel around it.

It took decades to end South African apartheid.BDS has being going on for at least 5 years. How long are you willing to wait for them to work? In 9 months 38,000 dead. 3 more years is another 150,000 and you are evidently cool with that.

We are there now with zionism, it will end soon.

zionists are hated globally and recognized as racial supremacists committing genocide, a description they share with nazis.

Idiotic lack of reasoning, Shazi. Netanayahu is the one stopping the return of the hostages, as you well know. That is why there are mass protests today against him in Israel. Ceasefire is the only way to get the hostages back and end the killing, on both sides, not to mention abiding by UNSC resolutions and the ICJ rulings.This is proof that you don't care how many die. A Hamas surrender and release of hostages stops the war immediately. Instead, you are literally saying that you want more and more Gazans to die. Demonizing Israel is more important to you Gazan lives.

I know you only think in terms of killing people and blowing things up, but that's not where real strength lies.

Hate speech, Shazi.All the Palestinians can do is use terror/violence as their number one export. Nobody wants them because they spread terror wherever they go. Not Jordan, not Egypt, not Yemen, not the Saudis, not UAE, not Qatar etc. Palestinians are the terrorists with no nation because they were too full of hate and violence to accept enough land to give them their own state in 1948.

You sound a nazi describing Jews in 1945.

Cut it out.

By posting 6 different links to news stories about the one report do you think it makes it look more important than other HRW reports?This is what HRW reported 3 days ago:

Hamas and other groups committed war crimes on 7 October - HRW (bbc.com)

Human Rights Watch report accuses Hamas, other militant groups of war crimes on Oct. 7 | CBC News

Hamas' War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity (HRW) (juancole.com)

Human Rights Watch Finds Hamas-Led Militants Committed War Crimes On Oct. 7 | HuffPost Latest News

October 7 Crimes Against Humanity, War Crimes by Hamas-led Groups | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org)

Hamas committed 'hundreds' of war crimes on October 7, HRW says - France 24

So many reports and your are too cowardly to comment on one report from HRW. Are you ashamed at all for people to see you ducking and dodging instead of being an honourable man/mensch and actually debating.

I could list dozens of HRW reports that you now must also accept, if you are arguing that HRW is trustworthy.

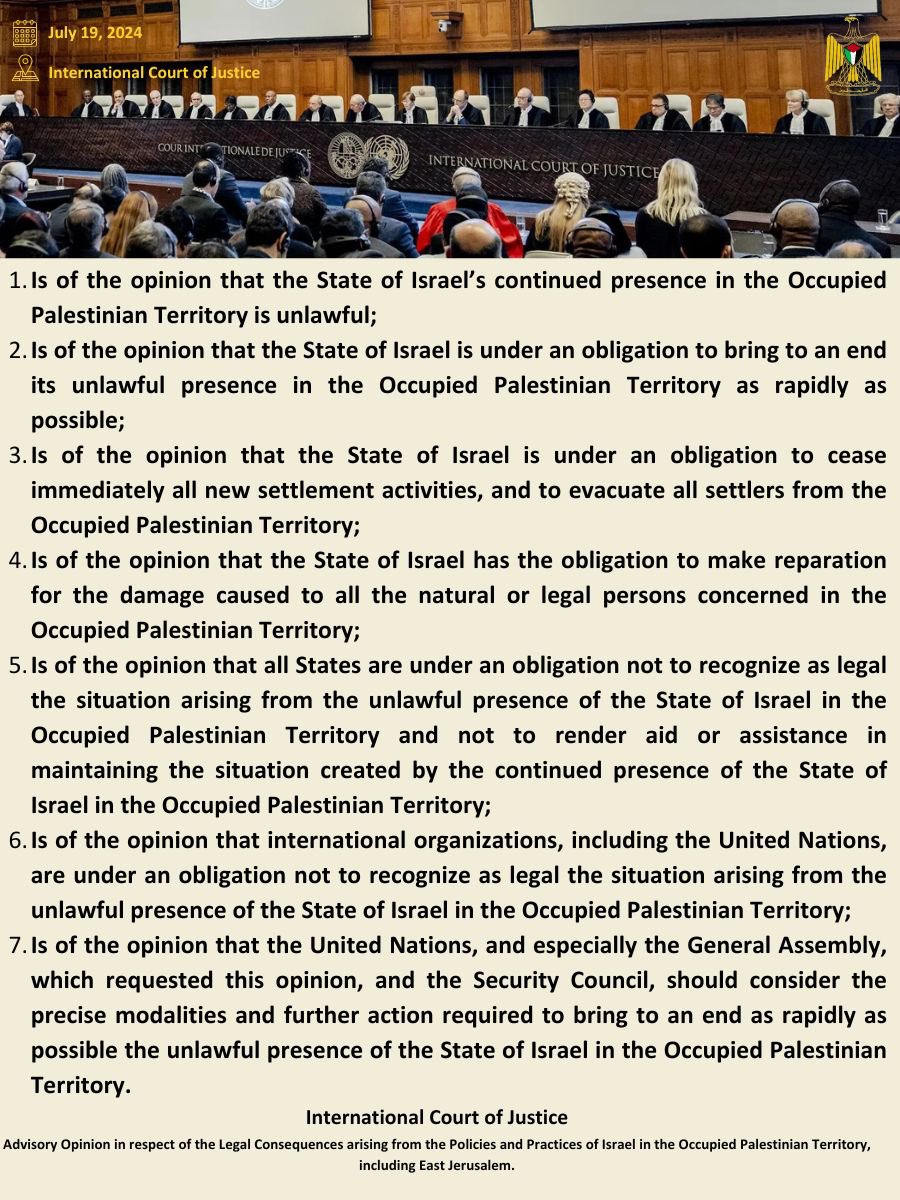

Lets start with this one, a 3 year old report now backed up by the latest ICJ decisions calling Israel apartheid and the occupation illegal.

A Threshold Crossed

The 213-page report, “A Threshold Crossed: Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution,” examines Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. It presents the present-day reality of a single authority, the Israeli government, ruling primarily over the area between the Jordan River and...

But please take that report to the ICJ where they will look at it and perhaps issue a ruling, as they will over charges of genocide and as they just did for the occupation. This is what carries the real legal weight internationally, with all states bound to honour these findings.

Shazi…..you should be on your hands and knees begging forgiveness from Frankfooter. The ICJ confirmed every assertion he made regarding POS Nations conduct. You, squealed like a little pig that he was wrong and it would never happen. It did and in spades.This is what HRW reported 3 days ago:

Hamas and other groups committed war crimes on 7 October - HRW (bbc.com)

Human Rights Watch report accuses Hamas, other militant groups of war crimes on Oct. 7 | CBC News

Hamas' War Crimes and Crimes Against Humanity (HRW) (juancole.com)

Human Rights Watch Finds Hamas-Led Militants Committed War Crimes On Oct. 7 | HuffPost Latest News

October 7 Crimes Against Humanity, War Crimes by Hamas-led Groups | Human Rights Watch (hrw.org)

Hamas committed 'hundreds' of war crimes on October 7, HRW says - France 24

So many reports and your are too cowardly to comment on one report from HRW. Are you ashamed at all for people to see you ducking and dodging instead of being an honourable man/mensch and actually debating.

Apologize to him. Maybe you will finally regain some dignity.