Israel at war

- Thread starter Butler1000

- Start date

Wouldn't be the first time these groups funnel money to extremist groups.

Canada Muslim charity under CRA microscope for ties to alleged Hamas front

In March 2021, the Muslim Association of Canada (MAC) got mail from the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) that no charity ever wants to see. In 150 pages, the letter detailed the CRA’s reasons for alleging, mid-audit, various breaches of tax law from 2013 to 2015, ranging from flawed record keeping to improper links to the Muslim Brotherhood and an alleged Canadian front for Hamas.

The letter, which was made public after being filed in a court proceeding brought by MAC challenging the audit, concluded with a daunting preliminary recommendation: “there are sufficient grounds for the revocation of the Organization’s charity registration.” MAC argued that the CRA conducted an unfair evaluation through a “Protestant-Christian lens” amounting to “systemic Islamophobia,” and that members’ freedom of religion, expression and assembly were violated.

A judge of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice dismissed MAC’s challenge to the audit in September, permitting the CRA to proceed. In a statement to the National Post on Friday, MAC said it intends to appeal the court’s verdict. It added that the CRA has made a final decision concerning the charity, which has not yet taken effect but “does not in any way affect MAC’s operations.” None of the allegations leveled by the CRA, which are denied by MAC, have been proven.

The CRA’s foremost claim is that MAC violated tax law by “advancing” the cause of the Muslim Brotherhood, an international Islamist movement with political and charitable arms that strives to implement Islamic law. The movement ascended to political power in Egypt in 2012, only to be ousted a year later; meanwhile, its Palestinian offshoot notably evolved into Hamas. Some countries have banned it, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. It has not been banned in Canada (though Hamas is).

One problem, the CRA said, arose from MAC’s governing documents. Its founding philosophy, according to its bylaws at the time of the audit, traced back to the “intellectual revivalist effort that occurred in the early 20th century” which culminated in the “writings of the late Imam Hassan al-Banna and the movement of the Muslim Brotherhood.” MAC explained to the auditors that it was referring to the broader philosophy of the movement, and not the Egyptian political party. In 2017, it removed any mention of the Muslim Brotherhood from its bylaws.

Some members of MAC’s senior leadership, the CRA alleges, were also “clearly engaging in activities that would be considered in support of the Muslim Brotherhood” which appeared to be manifesting in the organization’s activities and decisions.

Specifically, one former president of the organization was alleged to have worked on a political campaign for the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, a fact which the CRA believed he and MAC tried to conceal. The current president is said to have had an ongoing connection with senior members of the Muslim Brotherhood, illustrated by emails and conference invitations.

To its credit, MAC countered that the CRA based its claims on deficient research which unfairly characterized the Muslim Brotherhood as an “international network embracing radical ideas and violent extremism” by relying on biased academic and news sources. One academic source cited by the CRA, George Washington University extremism expert Lorenzo Vidino (who has previously testified before committee at the House of Commons) was argued by MAC to be tainted with anti-Muslim bias. MAC also argued that emails sent to its president were part of mass mail-out and that its president never attended any Muslim Brotherhood conferences.

Beyond that, the CRA claimed that until 2013 MAC had been providing resources to the International Relief Fund for the Afflicted and Needy (IRFAN) by allowing it to sponsor events, promoting it over email and giving it a platform to raise funds. IRFAN’s charity registration was revoked by the CRA in 2011, after an audit uncovered that the organization had sent more than $14.6 million to “operating partners that were run by Hamas officials.” By 2014, it was labelled a terrorist organization due to its support for Hamas.

Further, the CRA says MAC appeared to have accepted funds from Qatar Charity, which has been known for funding al-Qaida and is considered by Israel to be part of a Hamas fundraising network called “Union for Good.” More broadly, the CRA said MAC allegedly failed to implement an anti-terrorism policy in “a truly meaningful manner.”

MAC denies any such links: “It is categorically false to claim that MAC has ever provided support to Hamas, either directly or indirectly,” it said in its statement Friday. Furthermore, it says the RCMP has had no concerns with MAC’s donations to IRFAN, and that the CRA’s final decision concerning its audit of MAC was “not based on any preliminary findings associated with the Muslim Brotherhood, IRFAN Canada or Qatar Charity.”

The CRA also alleged that MAC was improperly dedicating an excessive amount of resources to exploring the real estate business and wrongfully bought rental properties to generate revenue (the charity’s property holdings were estimated to be worth $47 million in 2014). Financial controls were also said to be suspect: the CRA, for example, found that more than $1 million in charity funds, allegedly, had been given out to “non-qualified donees,” which should translate to a fine in a similar amount.

It’s easy to see why MAC took all this to court. Had it been deregistered, members would have suffered a certain loss of community. But the court challenge has seemed to be a bit of a strategic blunder. MAC failed to stop the audit from going through, having lost its court challenge in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in September. Before that, it tried and failed to seal part of the court record (it had argued, among other things, that disclosure of the CRA’s evidence would harm the “dignity, reputation and physical safety” of Muslim-Canadians), so the CRA’s case is now visible to the world.

The backbone of MAC’s argument just wasn’t convincing enough to call the audit off. It sought to halt the CRA’s audit process midway through largely on the grounds that it amounted to systemic discrimination. This was because rules for charities, and the CRA’s procedure for managing terrorism risk, disproportionately impacted Muslim charities and were therefore unfair. Judge Markus Koehnen, who presided over MAC’s court challenge, ruled that it would be premature to stop the CRA from combing through the file (though he was partially sympathetic).

So, how is the CRA’s audit discriminatory? MAC’s expert witness, University of Toronto Islamic legal scholar Prof. Anver Emon, believed that Finance Canada’s risk assessment model doesn’t have enough evidence to flag the following countries as being the most likely recipients of terrorism funding from Canada: Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Lebanon, Pakistan, the Palestinian territories, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Yemen. In the current “climate of Islamophobia,” this was a point of concern.

Emon also claimed that the government has failed to support its list of “terrorist groups with a Canadian nexus,” which it uses to asses charity risk. The list is comprised only of non-white and non-Christian groups, including Hamas, Hezbollah, the Islamic State group, al-Qaida, al-Shabbab, the Tamil Tigers and various Khalistani extremists (which, regardless of their demographic makeup, are still terror groups). Because these organizations were all based abroad, and because Finance Canada didn’t provide evidence to support the list, Emon argued, the CRA’s audit procedure implies that all terrorism risk comes from minorities, most of which are Muslim.

The fact that the government’s focus on foreign, largely Muslim entities when it came to terror financing risk, however, wasn’t necessarily evidence of discrimination, the judge of the court challenge found.

“It is perhaps not surprising that agencies whose mandate it is to monitor terrorist threats would focus on the more prominent threats at any one time,” wrote Koehnen. “In recent years, one major source of such threats has involved groups that pervert Islam and falsely cloak themselves in its mantle.”

Indeed, Canada had added white supremacist groups such as Blood & Honour to the terrorism list, but these just don’t seem to be big or globally-popular enough to warrant special CRA scrutiny.

Among the other systemic biases alleged against the CRA, Emon even found it troublesome that the agency seemed to give greater weight to documentary evidence than spoken word; this reliance on a paper trail indicated an Islamophobic “interpretive bias” because it implied that Muslims were inherently unreliable. The judge didn’t buy this, and said the CRA’s preference for documents was “standard litigation practice” when contradictory statements are made later on, during litigation.

Concerning MAC’s possible links to the Muslim Brotherhood and other foreign entities, though, the judge wasn’t convinced the CRA had a great case.

“The fact that a donor to a charity also donates money to illegal causes does not mean that the charity is involved in the illegal causes that the donor supports,” Koehnen reasoned.

In addition to that, the judge believed that political activity by former directors of Christian charities was unlikely to lead to the revocation of charity status. However, this was not enough to warrant halting the audit midway through.

“A brief look at the websites of the United, Anglican, Presbyterian and Catholic churches of Canada discloses web links about social action on issues like climate change, the economy, housing, resource extraction, Palestinian rights and LGBTQ+ rights that are similar to statements made by some Canadian political parties,” Koehnen wrote. “No one suggests their charitable status should be revoked because of that.”

MAC’s argument of systemic discrimination wasn’t novel. It was simply following the reasoning of a Supreme Court decision in 2020 which found that rules that don’t actively discriminate against any one group can still be considered discriminatory if they cause disproportionate outcomes for groups protected under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Depending on how far MAC plans to take its fight with the CRA, it’s possible that the rules for equity could be made to apply to charity finance. If it fails, however, it will have generated a lot of press for nothing.

nationalpost.com

nationalpost.com

Canada Muslim charity under CRA microscope for ties to alleged Hamas front

In March 2021, the Muslim Association of Canada (MAC) got mail from the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) that no charity ever wants to see. In 150 pages, the letter detailed the CRA’s reasons for alleging, mid-audit, various breaches of tax law from 2013 to 2015, ranging from flawed record keeping to improper links to the Muslim Brotherhood and an alleged Canadian front for Hamas.

The letter, which was made public after being filed in a court proceeding brought by MAC challenging the audit, concluded with a daunting preliminary recommendation: “there are sufficient grounds for the revocation of the Organization’s charity registration.” MAC argued that the CRA conducted an unfair evaluation through a “Protestant-Christian lens” amounting to “systemic Islamophobia,” and that members’ freedom of religion, expression and assembly were violated.

A judge of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice dismissed MAC’s challenge to the audit in September, permitting the CRA to proceed. In a statement to the National Post on Friday, MAC said it intends to appeal the court’s verdict. It added that the CRA has made a final decision concerning the charity, which has not yet taken effect but “does not in any way affect MAC’s operations.” None of the allegations leveled by the CRA, which are denied by MAC, have been proven.

The CRA’s foremost claim is that MAC violated tax law by “advancing” the cause of the Muslim Brotherhood, an international Islamist movement with political and charitable arms that strives to implement Islamic law. The movement ascended to political power in Egypt in 2012, only to be ousted a year later; meanwhile, its Palestinian offshoot notably evolved into Hamas. Some countries have banned it, such as Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. It has not been banned in Canada (though Hamas is).

One problem, the CRA said, arose from MAC’s governing documents. Its founding philosophy, according to its bylaws at the time of the audit, traced back to the “intellectual revivalist effort that occurred in the early 20th century” which culminated in the “writings of the late Imam Hassan al-Banna and the movement of the Muslim Brotherhood.” MAC explained to the auditors that it was referring to the broader philosophy of the movement, and not the Egyptian political party. In 2017, it removed any mention of the Muslim Brotherhood from its bylaws.

Some members of MAC’s senior leadership, the CRA alleges, were also “clearly engaging in activities that would be considered in support of the Muslim Brotherhood” which appeared to be manifesting in the organization’s activities and decisions.

Specifically, one former president of the organization was alleged to have worked on a political campaign for the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, a fact which the CRA believed he and MAC tried to conceal. The current president is said to have had an ongoing connection with senior members of the Muslim Brotherhood, illustrated by emails and conference invitations.

To its credit, MAC countered that the CRA based its claims on deficient research which unfairly characterized the Muslim Brotherhood as an “international network embracing radical ideas and violent extremism” by relying on biased academic and news sources. One academic source cited by the CRA, George Washington University extremism expert Lorenzo Vidino (who has previously testified before committee at the House of Commons) was argued by MAC to be tainted with anti-Muslim bias. MAC also argued that emails sent to its president were part of mass mail-out and that its president never attended any Muslim Brotherhood conferences.

Beyond that, the CRA claimed that until 2013 MAC had been providing resources to the International Relief Fund for the Afflicted and Needy (IRFAN) by allowing it to sponsor events, promoting it over email and giving it a platform to raise funds. IRFAN’s charity registration was revoked by the CRA in 2011, after an audit uncovered that the organization had sent more than $14.6 million to “operating partners that were run by Hamas officials.” By 2014, it was labelled a terrorist organization due to its support for Hamas.

Further, the CRA says MAC appeared to have accepted funds from Qatar Charity, which has been known for funding al-Qaida and is considered by Israel to be part of a Hamas fundraising network called “Union for Good.” More broadly, the CRA said MAC allegedly failed to implement an anti-terrorism policy in “a truly meaningful manner.”

MAC denies any such links: “It is categorically false to claim that MAC has ever provided support to Hamas, either directly or indirectly,” it said in its statement Friday. Furthermore, it says the RCMP has had no concerns with MAC’s donations to IRFAN, and that the CRA’s final decision concerning its audit of MAC was “not based on any preliminary findings associated with the Muslim Brotherhood, IRFAN Canada or Qatar Charity.”

The CRA also alleged that MAC was improperly dedicating an excessive amount of resources to exploring the real estate business and wrongfully bought rental properties to generate revenue (the charity’s property holdings were estimated to be worth $47 million in 2014). Financial controls were also said to be suspect: the CRA, for example, found that more than $1 million in charity funds, allegedly, had been given out to “non-qualified donees,” which should translate to a fine in a similar amount.

It’s easy to see why MAC took all this to court. Had it been deregistered, members would have suffered a certain loss of community. But the court challenge has seemed to be a bit of a strategic blunder. MAC failed to stop the audit from going through, having lost its court challenge in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in September. Before that, it tried and failed to seal part of the court record (it had argued, among other things, that disclosure of the CRA’s evidence would harm the “dignity, reputation and physical safety” of Muslim-Canadians), so the CRA’s case is now visible to the world.

The backbone of MAC’s argument just wasn’t convincing enough to call the audit off. It sought to halt the CRA’s audit process midway through largely on the grounds that it amounted to systemic discrimination. This was because rules for charities, and the CRA’s procedure for managing terrorism risk, disproportionately impacted Muslim charities and were therefore unfair. Judge Markus Koehnen, who presided over MAC’s court challenge, ruled that it would be premature to stop the CRA from combing through the file (though he was partially sympathetic).

So, how is the CRA’s audit discriminatory? MAC’s expert witness, University of Toronto Islamic legal scholar Prof. Anver Emon, believed that Finance Canada’s risk assessment model doesn’t have enough evidence to flag the following countries as being the most likely recipients of terrorism funding from Canada: Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Lebanon, Pakistan, the Palestinian territories, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Yemen. In the current “climate of Islamophobia,” this was a point of concern.

Emon also claimed that the government has failed to support its list of “terrorist groups with a Canadian nexus,” which it uses to asses charity risk. The list is comprised only of non-white and non-Christian groups, including Hamas, Hezbollah, the Islamic State group, al-Qaida, al-Shabbab, the Tamil Tigers and various Khalistani extremists (which, regardless of their demographic makeup, are still terror groups). Because these organizations were all based abroad, and because Finance Canada didn’t provide evidence to support the list, Emon argued, the CRA’s audit procedure implies that all terrorism risk comes from minorities, most of which are Muslim.

The fact that the government’s focus on foreign, largely Muslim entities when it came to terror financing risk, however, wasn’t necessarily evidence of discrimination, the judge of the court challenge found.

“It is perhaps not surprising that agencies whose mandate it is to monitor terrorist threats would focus on the more prominent threats at any one time,” wrote Koehnen. “In recent years, one major source of such threats has involved groups that pervert Islam and falsely cloak themselves in its mantle.”

Indeed, Canada had added white supremacist groups such as Blood & Honour to the terrorism list, but these just don’t seem to be big or globally-popular enough to warrant special CRA scrutiny.

Among the other systemic biases alleged against the CRA, Emon even found it troublesome that the agency seemed to give greater weight to documentary evidence than spoken word; this reliance on a paper trail indicated an Islamophobic “interpretive bias” because it implied that Muslims were inherently unreliable. The judge didn’t buy this, and said the CRA’s preference for documents was “standard litigation practice” when contradictory statements are made later on, during litigation.

Concerning MAC’s possible links to the Muslim Brotherhood and other foreign entities, though, the judge wasn’t convinced the CRA had a great case.

“The fact that a donor to a charity also donates money to illegal causes does not mean that the charity is involved in the illegal causes that the donor supports,” Koehnen reasoned.

In addition to that, the judge believed that political activity by former directors of Christian charities was unlikely to lead to the revocation of charity status. However, this was not enough to warrant halting the audit midway through.

“A brief look at the websites of the United, Anglican, Presbyterian and Catholic churches of Canada discloses web links about social action on issues like climate change, the economy, housing, resource extraction, Palestinian rights and LGBTQ+ rights that are similar to statements made by some Canadian political parties,” Koehnen wrote. “No one suggests their charitable status should be revoked because of that.”

MAC’s argument of systemic discrimination wasn’t novel. It was simply following the reasoning of a Supreme Court decision in 2020 which found that rules that don’t actively discriminate against any one group can still be considered discriminatory if they cause disproportionate outcomes for groups protected under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Depending on how far MAC plans to take its fight with the CRA, it’s possible that the rules for equity could be made to apply to charity finance. If it fails, however, it will have generated a lot of press for nothing.

Jamie Sarkonak: Muslim charity under CRA microscope for ties to alleged Hamas front

Muslim Association of Canada blames accusation on 'systemic Islamophobia'

Last edited:

20-year-old Ohio man arrested after he allegedly faked an anti-Palestinian hate crime

Investigators said the injuries came from a fight with his brother.

Catholics support Jews too, during the second world war many Italian families hid Jews from the nazis.If Islamic terrorists do attack the US they will be in for a rude awakening, much more so than what is happening in Gaza now.

As is much of North America, the US is majority Christian, and in the US there are a whole lot of Evangelical Christians.

As it is soon my birthday (fuck, another year older...), I received my annual birthday phone call from my brother's ex-wife. She is a devout Evangelical, End Of Times, Rapture style Christian.

She is totally incensed at how Israel has been treated, and believes that if the Messiah is to return (she believes it will be Jesus, who was a Jew, returning to carry out The Rapture), Israel must still exist as a Jewish nation.

First let me say that although I identify as a Jew by race, I am an atheist, and do not believe in God, Heaven, Hell, any sort of afterlife, and of course, Satan.

My ex-sister-in-law firmly believes that Allah is Satan, and not the Jewish and Christian Abrahamic God, and that Satan convinced Muhammad that he is God, and from that came all of Muhammad's intolerant & militant laws and teachings. She says her whole congregation is of the same belief.

There is nothing anyone can say that can change her mind on any religious issues, and I long ago gave up trying on most issues, including vaccines, etc.

So, long story short, any significant Muslim attack on North America, and especially the USA, will be met with a 9/11 response or much worse, and will make what is happening in Gaza seem like a day at the beach...

I no longer have sympathy for the Palestinians, after reading this.

Three in four Palestinians support Hamas’s massacre

Ninety-eight percent of respondents said the Oct. 7 slaughter made them feel "prouder of their identity as Palestinians."

(November 17, 2023 / JNS)

Slightly more than three in four Palestinians have a positive view of Hamas in the wake of its Oct. 7 terrorist attacks in Israel, according to a survey by the Arab World for Research and Development (AWRAD) research firm.

The Ramallah-based institute polled 668 Palestinian adults in the southern Gaza Strip, Judea and Samaria between Oct. 31 and Nov. 7. (The margin of error is plus or minus 4 percentage points, AWRAD said.)

The Palestinian poll—the first of its kind since the Oct. 7 attacks—found that 48.2% of respondents characterize Hamas’s role as “very positive,” while 27.8% view Hamas as “somewhat positive.” Almost 80% regard the role of Hamas’s Al-Qassam Brigades “military” wing as positive.

The Al-Qassam Brigades killed more than 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and wounded thousands in the Oct. 7 attack on southern Israel. In addition, terrorists took some 240 people hostage.

When asked whether they supported or opposed Hamas’s actions on Oct. 7, 59.3% of the Palestinians surveyed said they “extremely” supported the attacks and 15.7% said they “somewhat” supported the murderous spree.

Only 12.7% expressed disapproval with 10.9% saying they neither supported nor opposed the attack.

Almost all (98%) of the respondents said the slaughter made them feel “prouder of their identity as Palestinians,” with an equal percentage saying they would “never forget and never forgive” the Jewish state for its ongoing military operation against Hamas.

Three-quarters said that they expect the Israel-Hamas war to end in a Palestinian victory.

In response to the question “What would you like as a preferred government after the war is finished in Gaza Strip,” 72% said they favor a “national unity government” that includes Hamas and Palestinian Authority chief Mahmoud Abbas’s Fatah faction.

Approximately 8.5% said they favor a government controlled by the Palestinian Authority.

In addition, more than 98% of Palestinians surveyed by AWRAD hold negative views of the United States.

On Nov. 8, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that Gaza must be handed over to the P.A. following hostilities. The solution “must include Palestinian-led governance and Gaza unified with the West Bank under the Palestinian Authority,” stated Blinken.

During an Oct. 18 visit to Tel Aviv, U.S. President Joe Biden delivered a speech in which he claimed that “Hamas does not represent the Palestinian people.”

AWRAD said that “the poll’s sample includes all socioeconomic groups, ensuring equal representation of adult men and women, and is proportionately distributed across the West Bank and Gaza.”

www.jns.org

www.jns.org

Three in four Palestinians support Hamas’s massacre

Ninety-eight percent of respondents said the Oct. 7 slaughter made them feel "prouder of their identity as Palestinians."

(November 17, 2023 / JNS)

Slightly more than three in four Palestinians have a positive view of Hamas in the wake of its Oct. 7 terrorist attacks in Israel, according to a survey by the Arab World for Research and Development (AWRAD) research firm.

The Ramallah-based institute polled 668 Palestinian adults in the southern Gaza Strip, Judea and Samaria between Oct. 31 and Nov. 7. (The margin of error is plus or minus 4 percentage points, AWRAD said.)

The Palestinian poll—the first of its kind since the Oct. 7 attacks—found that 48.2% of respondents characterize Hamas’s role as “very positive,” while 27.8% view Hamas as “somewhat positive.” Almost 80% regard the role of Hamas’s Al-Qassam Brigades “military” wing as positive.

The Al-Qassam Brigades killed more than 1,200 people, mostly civilians, and wounded thousands in the Oct. 7 attack on southern Israel. In addition, terrorists took some 240 people hostage.

When asked whether they supported or opposed Hamas’s actions on Oct. 7, 59.3% of the Palestinians surveyed said they “extremely” supported the attacks and 15.7% said they “somewhat” supported the murderous spree.

Only 12.7% expressed disapproval with 10.9% saying they neither supported nor opposed the attack.

Almost all (98%) of the respondents said the slaughter made them feel “prouder of their identity as Palestinians,” with an equal percentage saying they would “never forget and never forgive” the Jewish state for its ongoing military operation against Hamas.

Three-quarters said that they expect the Israel-Hamas war to end in a Palestinian victory.

In response to the question “What would you like as a preferred government after the war is finished in Gaza Strip,” 72% said they favor a “national unity government” that includes Hamas and Palestinian Authority chief Mahmoud Abbas’s Fatah faction.

Approximately 8.5% said they favor a government controlled by the Palestinian Authority.

In addition, more than 98% of Palestinians surveyed by AWRAD hold negative views of the United States.

On Nov. 8, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that Gaza must be handed over to the P.A. following hostilities. The solution “must include Palestinian-led governance and Gaza unified with the West Bank under the Palestinian Authority,” stated Blinken.

During an Oct. 18 visit to Tel Aviv, U.S. President Joe Biden delivered a speech in which he claimed that “Hamas does not represent the Palestinian people.”

AWRAD said that “the poll’s sample includes all socioeconomic groups, ensuring equal representation of adult men and women, and is proportionately distributed across the West Bank and Gaza.”

Three in four Palestinians support Hamas’s massacre - JNS.org

Ninety-eight percent of respondents said the Oct. 7 slaughter made them feel "prouder of their identity as Palestinians."

Then the absolute quickest way to help them would be for Hamas to surrender and return all the hostages.I am not interested in talking about Hamas. They are a terror group.

I am only interested in talking about what Israel is doing to the Palestinian civilians.

Palestinian civilians are more important than Hamas.

Palestinian civilians are more important than Israel's military objectives.

Palestinian civilians are more important than Israeli hostages.

They are the ones that are more numerous, they are the primary victims here, and they are the ones vulnerable here. And they are the ones dying in huge numbers here. So let us focus on people that actually matter - the Palestinian civilians.

At that point negotiations could proceed to address all the issues for both sides and reach a peace agreement, which is what everybody agrees is the ultimate goal.

Negotiations have to take place at some point, so the sooner the fighting stops the sooner negotiations can be initiated. But, ALL THE HOSTAGES MUST BE RETURNED FIRST. Even a ceasefire needs to be negotiated which prolongs the suffering on Gazans.

If you are sincere about your concerns for Palestinians ASAP, Hamas has to step down ASAP. You hate them anyways. Nothing else helps Palestinians faster than that. Nothing is faster, not even a ceasefire.

By the way, thanks for such a balanced and neutral post. LOLOLOLOLOLOLOL What a joke.

What an absolute cop-out.Hamas is a terror group. There are and can be no expectations from terror groups. The military operation against Hamas has to proceed at some point, or resume at some point, to take them out, but as targeted assassinations and not as wide spread carpet bombings.

Therefore the absolute quickest way, would be to cease fire and start negotiations both for return of hostages and with the PA for resolution of the larger conflict.

Please notice, I said nothing about expectations.

I stated a fact that is irrefutable, the fastest way to help the Palestinians would be if they surrendered and released the hostages. You did not deny that that would be the fastest way, did you? All you did was come up with a suggestion would undeniably take much, much, much longer. Clearly you don't care about the immediate plight of the Palestinians. All you want is for the war to continue so as to help PR war.

You just admitted that my suggestion is by far, the fastest way to help the Palestinians. You cannot prove that statement wrong.

Wrong. Every cease fire has to be bilaterally negotiated. Hamas is negotiating for the release of the hostages and they can't even agree on that. How long will that take and how many more lives will be lost while they're also negotiating a ceasefire.?The fastest way to help Palestinians is to cease fire. Ceasing fire will not take long.

A surrender is a unilateral decision. Zero negotiations required. Immediate stoppage of violence.

Clearly my plan is a faster route to save lives. Irrefutable.

Who to negotiate with?Israel can agree to an unconditional humanitarian cease fire and then continue negotiating. That is the fastest way. Also, Israel should follow international law and not carpet bomb the Palestinians. Following international law should not have to be negotiated.

With the ones in the hotelsWho to negotiate with?

A Seismic Victory in Gaza: Mapping the Tunnels of the “Gaza Metro”

According to sources, Hamas’ tunnels under Gaza extend “a few dozen miles.” Other sources believe these tunnels extend hundreds of miles and rival the underground of a major European

A Seismis Victory In Gaz: Mapping The Tunnels Of The "Gaza Metro"

SATURDAY, NOV 18, 2023 - 09:20 AM

Authored by Malcom E. Whittaker via RealClear Wire,

According to sources, Hamas’ tunnels under Gaza extend “a few dozen miles.” Other sources believe these tunnels extend hundreds of miles and rival the underground of a major European city. This has caused some commentators to refer to Hama’s tunnels as the “Gaza metro.” The ‘Gaza metro’: The mysterious subterranean tunnel network used by Hamas | CNN. Whatever their length, they shield fighters from surveillance and allow movement without fear of observation or attack. What if these tunnels could be precisely located? Rather than being safe locations, they would become death traps.

Commentators suggest the tunnels give Hamas an asymmetric advantage. The noted publication Foreign Affairs, states that only “ulldozers can be used to expose tunnels during a ground operation. Drones, robots, or dogs can help clear tunnels. There might be a need to enter the tunnels to rescue hostages, as a measure of last resort. … This is how most states have eliminated subterranean threats in the past, and this is what Israel should do, as well.” (November 9, 2023, “Israel Must Destroy Hama’s Tunnels, Demolishing the Groups Infrastructure Is More Important Than Eliminating Its Leaders”). In short, according to Foreign Affairs, only personnel on the ground can locate and destroy Hama’s tunnels. Of course, Israeli personnel searching open ground to locate the entrances to the tunnels would be exposed to attack.

Currently used seismic equipment could locate tunnels using a system of geophones and pulse generators. However, personnel placing the geophone data acquisition equipment on the surface would be exposed to small arms fire and potential capture. The need to potentially expose personnel to attack while emplacing geophones would seem to defeat use of this well-understood technology that could readily and accurately locate Hama’s tunnels.

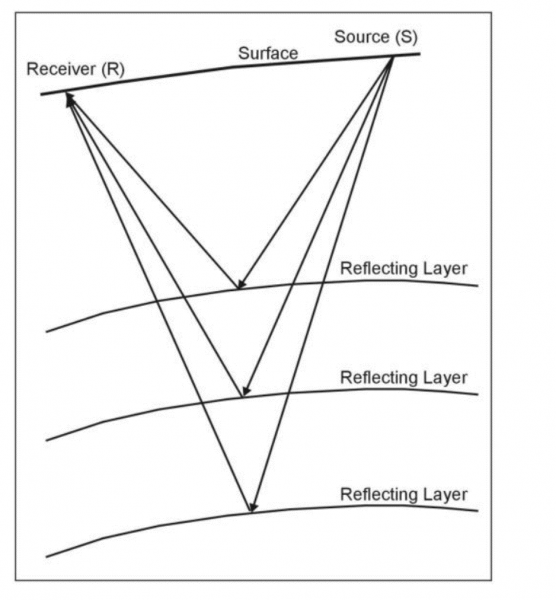

At its most basic, a seismic system can map layers in the earth’s surface. To do so, as seen in the figure below, a source generates a seismic wave. This wave travels through the earth and reflects off reflecting subsurface layers, such as the roof and floor of a tunnel, and these reflected waves are collected by a receiver. A source and be anything that generates a seismic wave. Currently, stamper trucks and explosives are frequently used to generate these waves. Seismic receivers are generically referred to as “geophones.” Geophones collect seismic data, i.e., seismic waves, and map the earth’s subsurface.

Current seismic technology readily available from the oil field will allow identification (and then destruction) of these tunnels. Wireless Seismic METIS (Multiphysics Exploration Technology Integrated System) uses a seismic recording channel collected by autonomous drones. These drones also drop DART (Downfall Air Receiver Technology) receivers, i.e., geophones. The DARTs are dropped by the drone and impale themselves into the ground creating a system of geophones to model the subsurface data. This system was thoroughly evaluated in Papua New Guinea in 2018. Wireless Seismic News — METIS field test yields excellent results. A single drone dropped 60 DARTs in one hour and these drones recovered “real time seismic data” thereby imaging subsurface data of underground voids. Precision guided artillery shells could provide the seismic source needed for the geophones to collect subsurface data. The DART’s would be dropped inside Gaza to model any location, i.e., not just locations close to where Israeli troops are located. Thus, METIS could accurately map the entire Gaza strip.

Once the location of the tunnels is known, they can be destroyed using deep penetrating bombs fused to detonate deep in the ground and dropped from aircraft. This could potentially interdict the entire system of tunnels. Even an extensive metro-like system of tunnels could be defeated if important chokepoints could be detected and collapsed.

Finally, this technology could resolve the ongoing factual dispute over whether Hamas has placed tunnels underneath hospitals, United Nations positions, schools, and other places that are protected from attack. While not a panacea, the METIS system could answer these basic questions and, potentially, turn Hama’s tunnels into a death trap for fighters using the tunnels. At least, it would mitigate any asymmetric advantage Hama’s tunnels provide.

Malcolm E. Whittaker is a former candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives. Malcolm is an engineer and patent attorney in Houston, Texas.

My my. So much for the dismembered bodies and burned bodies.

Looks like the IDF screwed up again and tried to blame it on Palestinians.

Looks like the IDF screwed up again and tried to blame it on Palestinians.

Ow Christians in Jerusalem are asking for assistance as Israel tries to eliminate other religions from the Occupied Territories.

Exactly, there is nobody to negotiate with. Hamas has a choice to release civilian hostages for a ceasefire, but refuse to. Speaks volumes.Who to negotiate with?

And second, its text book that you do not negotiate with TERRORISTS!Exactly, there is nobody to negotiate with. Hamas has a choice to release civilian hostages for a ceasefire, but refuse to. Speaks volumes.

Even accepting your figures - and I don't - those casualties were caught in a war zone. Urban fighting causes a lot of collateral damage.Given 11,000+ civilians, and 5000+ children are dead, Israel is not taking any precautions and indiscriminately bombing them. It is a war crime. Israel so far has not shown any military advantage that justifies this many deaths. So per international law, it is a war crime and am sure the ICC investigation will find the same.

Well, what would YOU call the HAMAS terrorists who raped, killed and tortured their victim???!!!!.... Oh that's right. THEY'RE ANTI COLONIALIST FREEDOM FIGHTERS!! OF COURSE!That is ignorant. Being center left, or hating Tories or the GOP does not mean one cannot be racist. The comments on this thread, that I have called out time and again, that have described the Palestinians as savages, barbarians etc, while showing ZERO empathy for their suffering, is an example of racism. By any objective measure, it is racist.

You got any posts of anyone calling ordinary Palestinians by racist names??

It's over. It happened decades ago and the current occupier has a large, very proficient army and nukes. They ain't getting Palestine back. And they shouldn't even be trying.You or I, do not decide what is over and what isn't. The people involved in the conflict do. And they have determined that it is not over. So it is not over. If it was over, we wouldn't have a conflict in the first place.

What's happening here is that a bunch of super rich corrupt HAMAS leaders take Russian and Iranian money to stir shit. And they keep their sad, fucked up cause alive, so they don't have to provide a decent living and future to the ordinary Gazans.

Let's go through a list of other land seizures and you can tell me if "it's over", or not.

1864 - Germany seizes Schleswig-Holstein from Denmark

1908 - Austria seizes Bosnia-Herzegovina from Turkey

1913 - Bulgaria seizes Thrace from Turkey

1918 - Romania seizes Transylvania from Hungary. Does Hungary get to attack Romania to seize Transylvania back in 2023?.... Answer is "NO!"

1918 - Italy seizes South Tyrol from Austria.

1918 - France gets Alsace-Lorraine from Germany.

1945 - Poland gets Silesia and East Pomerania from Germany.

1945 - Ukraine gets Lviv from Poland.

1945 - Russia gets East Prussia from Germany

1945 - Lithuania gets Memel from Germany

Does Germany get to raid Poland or any of those other countries to get Silesia back??.... No. It's stupid. It's done. It's over. Time for everyone to move the fuck on.

The Gazans should have been filtered into other Arab countries and given new lives and a better future. Didn't happen. Why?..... Because HAMAS has thoroughly infiltrated and controlled Gazan society and the refugees have attempted to overthrow moderate Arab governments in every country that they have been allowed to enter.

Actually the British had every right. It was their land. They owned and ran the joint. So they got to decide who rented rooms there. Legally it was British territory. So there you go.No it is not. It is the blunt truth. The British, did not have any right to colonize a land, paper partition it with France, and hand it to a people who did not even live there for the most part. The Balfour declaration is acknowledged as a British mistake. So you do not take Arab land, and then hand it to foreigners and then mandate that the Arabs "accept" it. Why should they?

Not going to happen because you can't cut deals with the Palestinians. First of all, HAMAS won't take the deal because of their "River to the Sea" horseshit. Second - even if they did - they would just use it as a regrouping pause to attack Israel again.But that aside, because it is history now, the occupation after 1967 with settlements in stolen land (that Israel calls "disputed"), is wholly illegal. On top of this, Israeli settlements are not just a thing of accident. It is done strategically to steal water resources, fertile land and to cut up the Palestinian population into enclaves.

Former Prime Minister of Israel Ariel Sharon said in 1973: “We’ll make a pastrami sandwich of them. We’ll insert a strip of Jewish settlement in between the Palestinians and another strip of Jewish settlement right across the West Bank so that in 25 years’ time neither the U.N. nor the U.S., nobody will be able to tear it apart.”

Again, in 1998 shortly before being elected prime minister, Sharon wrote: “Everyone has to move, run and grab as many hilltops as they can to enlarge the settlements because everything we take now will stay ours … Everything we don’t grab will go to them.”

So, yes, it is illegal, stolen land. All of this is driven by Zionism, which is really about creating a racist ethno-state and amounts to colonialism. So you do not steal land, and then expect that the Palestinians will just accept a peace agreement. You have to GIVE BACK land. Or incorporate them as EQUAL citizens under a secular, democratic system. That is what will bring about an end to the conflict.

Of course Israel is going to do that. How tf else are they going to stop HAMAS from coming back?!Wait and watch. At the end of this war, Israel will grab more land. They will call it a "security zone" or something like that and take over Northern Gaza and squeeze the Palestinians into Southern Gaza. Where those people will go through even more hardships which will cause even more terrorism. Then will come the settlements in Northern Gaza, because Israel will argue that they "conquered it" and that it is "disputed". They will flood that region and then make it impossible to move out. At the end of the day it is about taking as much land as possible, and squeezing the Palestinians into as small of a territory as possible.

Bullshit to both of those assertions.Firstly, colonialism is not "over". It never was. It just changed forms. Secondly, nobody supports Hamas.

Unfortunately the real world has HAMAS, not your idyllic image of nice, polite, suffering Gazan women and children. So you're wrong again.People support Palestinians. People oppose Israeli atrocities like bulldozing homes, forcefully evicting people from their homes, unlawfully detaining people without trial (including children) to steal land and brutalize people. People also oppose, the racism, apartheid and dehumanization that Israel subjects the Palestinians to. Not making an explicit distinction between Palestinians and Hamas, is also, racism. That is like saying all Muslims are terrorists. That makes it easier to justify collective punishments, but as I said before, it all amounts to racism, colonialism and war crimes.

I am not interested in talking about Hamas. They are a terror group. I am only interested in talking about what Israel is doing to the Palestinian civilians.

Palestinian civilians are more important than Hamas.

Palestinian civilians are more important than Israel's military objectives.

Palestinian civilians are more important than Israeli hostages.

They are the ones that are more numerous, they are the primary victims here, and they are the ones vulnerable here. And they are the ones dying in huge numbers here. So let us focus on people that actually matter - the Palestinian civilians.

You really think negotiations with Hamas in Qatar is possible?Why because you heard it in a hollywood movie? lol.

You negotiate with Hamas via Qatar.

My condolences about your family.If Islamic terrorists do attack the US they will be in for a rude awakening, much more so than what is happening in Gaza now.

As is much of North America, the US is majority Christian, and in the US there are a whole lot of Evangelical Christians.

As it is soon my birthday (fuck, another year older...), I received my annual birthday phone call from my brother's ex-wife. She is a devout Evangelical, End Of Times, Rapture style Christian.

She is totally incensed at how Israel has been treated, and believes that if the Messiah is to return (she believes it will be Jesus, who was a Jew, returning to carry out The Rapture), Israel must still exist as a Jewish nation.

First let me say that although I identify as a Jew by race, I am an atheist, and do not believe in God, Heaven, Hell, any sort of afterlife, and of course, Satan.

My ex-sister-in-law firmly believes that Allah is Satan, and not the Jewish and Christian Abrahamic God, and that Satan convinced Muhammad that he is God, and from that came all of Muhammad's intolerant & militant laws and teachings. She says her whole congregation is of the same belief.

There is nothing anyone can say that can change her mind on any religious issues, and I long ago gave up trying on most issues, including vaccines, etc.

So, long story short, any significant Muslim attack on North America, and especially the USA, will be met with a 9/11 response or much worse, and will make what is happening in Gaza seem like a day at the beach...

Personally, I think Israel is going to do a pretty thorough job on HAMAS. Those HAMAS leaders will be assassinated in Turkey and Yemen, just like the US got ObL. And we'll see what the IDF will do to HAMAS in Gaza.