Unicorns, Nah that's crazy talk. Could be Llamas, in particular Carl. I don't trust that guy.Isn't that the plan for all the oil despots?

Why Warming Oceans Matter

- Thread starter niniveh

- Start date

I'm sure you don't trust scientists.Unicorns, Nah that's crazy talk. Could be Llamas, in particular Carl. I don't trust that guy.

I'm sure you don't trust scientists.

Gazing into the future should really make us sweat |

| By David Wallace-Wells Opinion Writer |

On the last day of July, Phoenix finally registered a temperature high below 110 degrees Fahrenheit — the first time that had happened in 31 days. The temperature of pavement in the city measured up to 180 degrees, and local burn units are full of patients who simply fell to the ground and were burned, as though Maricopa County’s whole surface were a skillet on the stove. The I.C.U.s are filling up, too, and the region’s iconic saguaro cactuses are crumpling and collapsing in the heat. On the same day last week that President Biden offered only a few meek remarks about extreme heat and just a few million dollars in new funding for heat forecasting, the U.N. secretary general, António Guterres, leaned into a typically vehement formulation. “The era of global warming has ended,” he said. “The era of global boiling has arrived.” |

It was, worldwide, the hottest month on record. June was the hottest June on record. August appears poised to be the hottest August. Every single day for four straight weeks, as Canada burned and Sicily burned and Algeria burned, global temperatures surpassed the daily record set in 2016 and matched last summer, when 61,000 Europeans are estimated to have died as a result of the heat. |

But what else do you expect as greenhouse gas emissions continue? On opposite ends of the planet, temperatures recorded in the North Atlantic and sea ice measured near the South Pole, tracked so far from recent trends that you might embarrass yourself simply stating the size of the anomaly — a four sigma event in the temperatures of the North Atlantic, meaning that, given a stable climate and a normal distribution of chance, it should be expected about once every few hundred years and perhaps a six sigma event for Antarctic sea ice, meaning we should expect to see it, at least according to the simplified math, only once every 7.5 million years. |

At a certain point, that math just gets silly, telling you perhaps more about the improper way you might have structured the comparison than about the size of the anomaly itself. But you can measure the anomalies in other ways, such as by noting the hot-tub ocean temperatures off the Florida Keys, a year’s worth of rain falling in 36 hours in parts of Beijing or 100-degree temperatures in the mountains of Chile or that there is an Argentina-size gap between this year’s Antarctic sea ice and the typical extent. And the fact that we are seeing these gob-smacking anomalies at all is a sign that the historical framework implied by terms like “seven sigma” and “500-year storm,” imperfect in the best of times, no longer applies to the world we live in now. |

The environmental journalist Juliet Eilperin called the ocean temperatures “beyond belief”; The Washington Post reported that they had “baffled scientists.” Contemplating the trajectory of Arctic sea ice, the atmospheric scientist Zack Labe wrote memorably about how often he finds himself answering questions about the state of the science these days by saying, “I don’t know.” And for all the uncertainty, many of those watching the changes unfold have a queasy intuition that we may be entering a new climatic regime — and perhaps inching closer to some quite concerning tipping points. |

“Shocking but not really surprising,” is how NASA’s Gavin Schmidt put it. “Even the things that are unprecedented are not surprising.” That is where we are all living now, in a climate that is both shocking and unsurprising. For several decades, those anxious about global warming have lived in fear of climate prophecies. We are beginning to simply live within them, a process that looks from some vantages like a horror story and from others surprisingly normal. |

There are different ways to measure the changes, some less hair-raising than others. In a report published July 25, the World Weather Attribution network examined recent heat waves in the United States, Europe and China, finding that all but the Chinese event would have been impossible without climate change. In a stable, prewarming climate, the heat wave that baked China would have happened once every 250 years; now, the network said, it should be expected every five years. The episodes in Europe and North America, once impossible, should be expected once every 10 to 15 years. I’d bet on these frequencies being underestimates. Last summer there were 100 million Americans under heat advisories, and heat across Europe was called record-breaking then, as well. (On British television, a broadcaster complained that her meteorologist guest was being too gloomy about the heat; “I want us to be happy about the weather,” she said. In the weeks that followed, several thousand Britons died in the heat.) |

But the World Weather Attribution report also characterized the heat waves in another way, incorporating a critique made by Patrick Brown of the Breakthrough Institute last summer to measure the simple size of the temperature anomaly attributable to climate change, too. By this metric, the network found, warming had added just one degree Celsius to the temperatures in China, two degrees to the heat waves in North America and two and a half degrees to southern Europe’s. |

The coolheaded climate scientist Zeke Hausfather tried to quickly contextualize the recent string of anomalies to show that, in fact, they were, while alarming, nevertheless within the range of expected outcomes, given the present level of global warming. Well, at least two of the three anomalies he examined — the Antarctic sea ice was still quite off the charts. (About those, one scientist told The Guardian that “something weird is going on”; another said that the abrupt changes were “very much outside our understanding of this system.”) |

But even if, in most cases, the science is vindicated by this summer’s extremes, that isn’t ultimately all that reassuring. Forecasts for warming have long scared many of those who really looked at them, and so it’s not exactly comfortable to know that we are merely coasting along the high end of those forecasts today. As the climate stalwart Bill McKibben put it to me recently, when it comes to global warming, “‘I told you so’ are the four least satisfying words in the language.” |

“The speed of us passing limits is mind-bending,” wrote the Texas A&M atmospheric scientist Andrew Dessler, with whom Hausfather shares a Substack, in a short reflection on why climate impacts seemed to be escalating so quickly. “When the Earth warms the next 0.1 degrees Celsius, an entirely new group of thresholds will be passed, bringing great harms to entirely different groups of people,” he wrote. “Many of them will not expect it, having been lulled into complacency by the fact that they hadn’t been negatively impacted by warming up to then. Is that you?” |

As the extreme events have piled up this summer, I keep returning to a conversation I had last fall with the Texas Tech atmospheric scientist Katharine Hayhoe, a lead author of several U.S. National Climate Assessments and the chief scientist at the Nature Conservancy. |

“The good news is we have implemented policies that are significantly bringing down the projected global average temperature change,” she said, describing a suite of projections now showing expected temperature rise this century of two to three degrees Celsius rather than four to five. But the bad news was that we had been “systematically underestimating the rate and magnitude of extremes.” Even if temperature rise is limited to two degrees, she said, “the extremes might be what you would have projected for four to five.” |

In a long essay I published soon after that conversation, I emphasized that good news — that thanks to the technological and economic miracle of renewables, a global political awakening and an understanding that some earlier assumptions about future energy use were too pessimistic, we had about cut in half our expectations of warming in less than a decade. |

This summer, I’ve been thinking more about her bad news — that even accounting for rapid global decarbonization and a drastic cut in expected global temperature rise, we may still end up in a world defined by impacts long called catastrophic. For now, it seems scary enough to say, we don’t really know. |

Parts of the US are set to hit dangerous wet bulb temperatures.

By David Wallace-Wells

Opinion Writer

David Wallace-Wells is an interesting guy. While he did say people should be

scared he also came across as optimistic about the climate future of the planet.

I guess that wimp is fine with people just turning on AC when sweating.

scared he also came across as optimistic about the climate future of the planet.

I guess that wimp is fine with people just turning on AC when sweating.

By David Wallace-Wells

Opinion Writer

Feeling guilty today?David Wallace-Wells is an interesting guy. While he did say people should be

scared he also came across as optimistic about the climate future of the planet.

I guess that wimp is fine with people just turning on AC when sweating.

Feeling guilty today?

Denial, Denial, Denial...must be a river in Africa..

How climate scientists feel about seeing their dire predictions come true

(Shutterstock)

BY CORINNE PURTILLSTAFF WRITER

AUG. 18, 2023 6:24 AM PT

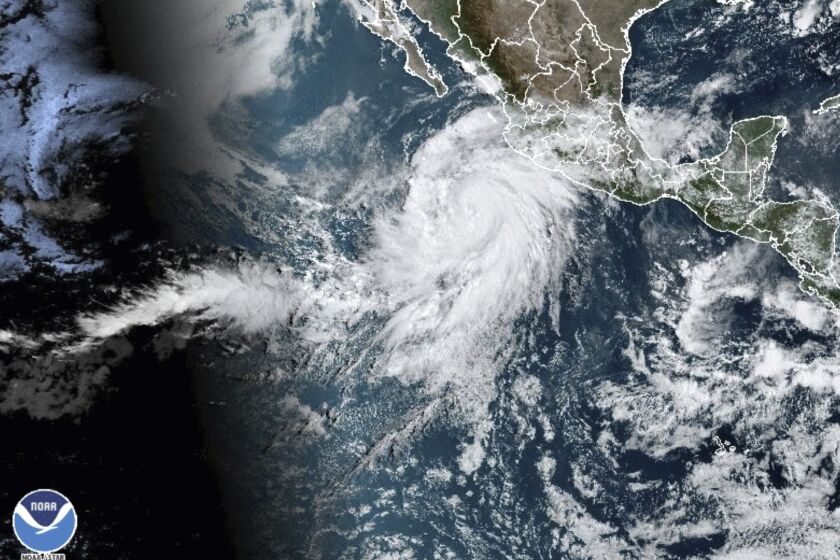

You are correct. It is, in fact, extremely unusual to be on hurricane watch in Southern California.

If Hurricane Hilary continues on the trajectory forecasters are currently predicting, it will be the first tropical storm to make landfall in California since 1939, and only the second one to do so since the 19th century.

If this seems like a worrying development to you, one in a string of recent climate-related disasters that seem to portend the arrival of a deeply unpleasant future, you are right about that as well.

And the people who have spent careers thinking about climate change and its likely consequences, who have read the papers and reviewed the models and warned about these potential catastrophes for years — they’re worried too.

ADVERTISEMENT

It’s been 35 years since an explicit reference to climate change first appeared on the front page of a U.S. newspaper, after James Hansen, then director of NASA’s Institute for Space Studies, testified before the Senate that “the greenhouse effect has been detected, and it is changing our climate now.”

In the decades since, the effects of climate change have loomed ominously in the distance like the due date of an unpayable mortgage.

But 35 years is enough time for a mortgage to come due, for children to grow up and have children of their own, and for the long-feared consequences of a warming world to become reality.

For climate scientists, it doesn’t feel good to be proved right.

CALIFORNIA

Hurricane Hilary is upgraded to Category 4, amplifying danger to Southern California

Aug. 18, 2023

“I used to think, ‘I’m concerned for my children and grandchildren.’ Now it’s to the point where I’m concerned about myself,” said Mike Flannigan, a professor of wildland fire at Thompson Rivers University in Edmonton, Canada.

The Times spoke with several researchers and climate experts about how the recent string of record-breaking, precedent-setting events feel to them. Their comments have been lightly edited for clarity.

ADVERTISEMENT

‘There’s just too much’

Charles Johnson gulps down a third bottle of water on a extremely hot July day in Blythe, Calif.

(Irfan Khan/Los Angeles Times)

Daniel Swain is a UCLA climate scientist who studies how climate change affects extreme weather events.

This seemingly constant onslaught of extremes, unprecedented weather and climate events — yes, it is different.

Yes, extreme weather disasters happened previously. But we really are seeing a pretty dramatic escalation. It’s gotten less coverage, but the majority of the population of the northwest territories of Canada were evacuated last night [Wednesday] because all of the major settlements are threatened by separate fires. All of them.

It’s an example of how there is now so much going on that it is difficult even to digest it all. There’s just too much. It’s everything everywhere all at once when it comes to extreme climate events this year.

ADVERTISEMENT

— Daniel Swain, UCLA climate scientistIt’s everything everywhere all at once when it comes to extreme climate events this year.

The amount of global warming we’ve seen is remarkably close to median projections for where we would be at this point. But is the increase in certain kinds of extreme events — and in particular the societal and ecological effects of those increasing extreme events — greater than had been predicted? It’s fair to say the answer is yes.

At this point, every unprecedented extreme heat event has a human fingerprint on it. It would be extraordinarily unlikely for a study to come out and say, “Oh, amazingly, this is a unique heat wave in that it wasn’t made worse by climate change.” Good luck with that. Same thing with really extreme precipitation events. And increasingly, in many places, the same thing is true for things like wildfires.

‘Climate change denial will cost us more and more lives’

A home collapsed onto a beach last year in Haleiwa, Hawaii, a victim of rising seas and more intense storms.

(Dan Dennison/Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources via Associated Press)

Craig Smith is an oceanographer at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. He specializes in deep-sea ecosystems, whose fragile natures and slow rates of recovery leave them particularly vulnerable to climate change.

All these climate-related catastrophes occurring in quick succession this year are extremely worrying! They drive home the point that climate-enhanced catastrophes are real and accelerating, heightening the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adopt realistic mitigation strategies as quickly as we can.

ADVERTISEMENT

These catastrophic events, such as the Lahaina fire, really drive home the monetary and human costs that will result from climate inaction. Delaying investments in sustainable energy and climate adaptation (such as coastal retreat in response to sea-level rise) is penny-wise but immensely pound-foolish. Climate change denial will cost us more and more lives.

‘We’re in uncharted territory. And that’s scary’

Flames burn inside a van during the Camp fire that tore through Paradise, Calif., in 2018.

(Noah Berger / Associated Press)

Mike Flannigan is a fire scientist at Thompson Rivers University.

Things are crazy. We’re in uncharted territory. And that’s scary. Frightening.

I’ve been doing this for over 40 years, and our models of temperature increases have been pretty darn good. But the impacts are more severe, frequent and intense than I expected. Things are happening, in terms of impact, much more rapidly than I expected.

ADVERTISEMENT

It was always like, “Well, yes, I’m really worried about 30, 50 years from now.” Now, I’m worried about what’s going to happen next year, let alone the next 10 or 20 years.

— Mike Flannigan, a fire scientist at Thompson Rivers UniversityI’m worried about what’s going to happen next year, let alone the next 10 or 20 years.

I hope this year is a turning point, but I’ve been disappointed before. A colleague and I wrote a paper in the late ‘90s that said, “Urgent action is needed now to deal with climate change.” I still give talks and at the end I often say, “Urgent action is needed on climate change.” But I’m getting bloody tired of saying this, because we’re not doing enough.

‘Climate action should be viewed as an act of survival’

People in New York City take photos of the sun as smoke from wildfires in Canada engulfs the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions of the U.S.

(Angela Weiss / AFP via Getty Images)

Jonathan Parfrey is executive director of Climate Resolve, a Los Angeles nonprofit that works toward equitable climate solutions.

ADVERTISEMENT

People are finally waking up to the reality of climate change. Unfortunately, due to the phenomenon of climate inertia — the massive additional energy that’s been absorbed by the oceans — the die is cast. Our future will grow even hotter.

Climate activism should not be considered an altruistic endeavor. Instead, climate action should be viewed as an act of survival, a necessity.

This moment is a strange mix of grief and hope. On the one hand, I know how precarious our situation is. On the other, we have the tools and ideas, if put into action, that can make a world of difference.

CALIFORNIA

The complete guide to storm safety preparedness

Aug. 18, 2023

CLIMATE & ENVIRONMENTSCIENCE & MEDICINEWORLD & NATION

Corinne Purtill

Corinne Purtill is a science and medicine reporter for the Los Angeles Times. Her writing on science and human behavior has appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, Time Magazine, the BBC, Quartz and elsewhere. Before joining The Times, she worked as the senior London correspondent for GlobalPost (now PRI) and as a reporter and assignment editor at the Cambodia Daily in Phnom Penh. She is a native of Southern California and a graduate of Stanford University.

MORE FROM THE LOS ANGELES TIMES

OTIS CATEGORY 5 LEVELS ACAPULCO

Acapulco Saw the Future of Hurricanes: More Sudden and Furious

Nov. 1, 2023

Credit...Ibrahim Rayintakath

- Share full article

By David Wallace-Wells

Opinion writer

You’re reading the David Wallace-Wells newsletter, for Times subscribers only. The best-selling science writer and essayist explores climate change, technology, the future of the planet and how we live on it.

As of last Monday night in Acapulco, Mexico, no formal hurricane warning had been issued for what would become, barely a day later, the first Category 5 storm ever to make landfall on the Pacific Coast of North or South America.

Forecasts from 36 hours before landfall had projected maximum winds of 60 miles per hour. Sixteen hours before landfall, the National Hurricane Center still forecast only a Category 1 hurricane. Within hours, what had been a quotidian tropical storm grew into a record-breaking, city-splintering Category 5 monster. The wind reached 165 miles per hour, more than 100 miles per hour greater than had been forecast around bedtime on Monday. Dozens died. The resort city, home to one million people, was left “in ruins”: the electricity cut out, as did water and internet service. The damage was almost certain to make the storm the most expensive one in Mexican history. “In all of Acapulco there is not a standing pole,” President Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico said on Thursday. One station registered wind above 200 miles per hour; the local forest was so thoroughly cleared of branches and leaves that satellite images flipped from green to brown. Some large high-rises had been ripped apart, others made skeletal; you could see clear through the building frames, an empty stack of boxes open to the winds. A day or two before, people living in those apartments might not have even heard about the storm.

The damage is, if spectacular, also tragically familiar. But the out-of-nowhere arrival is profoundly new. Hurricane Otis had the second-most drastic intensification of any storm on record in the eastern Pacific. The most dramatic one intensified much farther from shore, and did not make landfall as a Category 5.

In this way, Otis seems less like our conventional experience of hurricanes, according to which vulnerable communities are afforded by meteorologists perhaps a week of warning and a few calm days for evacuation, than of wildfires, which can spark so suddenly and spread so rapidly that those living in high-risk areas often spend weeks of summer on red-flag alert ready to evacuate on just a few hours’ notice. High water temperature is to hurricanes what low humidity and strong winds are to wildfires, and perhaps those living on hurricane-prone coasts will soon begin monitoring ocean heat like those living in the wildland-urban interface routinely track “fire weather,” knowing what unusually warm conditions offshore mean for what a new storm might quickly become.

ADVERTISEMENT

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Although, conventionally, hurricanes are measured by their peak intensity, how quickly they reach that intensity and how rapidly they approach land matters enormously. Over the last century, the world has made remarkable if unequal progress in reducing human mortality from storms, even as tallies of property damage have appeared to grow larger. Much of that progress is thanks to better forecasting and early warning systems — having a few days, rather than a few hours, to prepare makes even the most brutal storms much easier to endure and survive. A tropical storm isn’t an insignificant threat, and what became Otis surely would’ve damaged Acapulco even if it hadn’t ever intensified. But a Category 5 is a threat of a different order, requiring an entirely different scale of preparatory response. You simply can’t evacuate a city of one million in just a few hours — at least, it’s never been managed before.

A changing climate, a changing world

Card 1 of 4

Climate change around the world: In “Postcards From a World on Fire,” 193 stories from individual countries show how climate change is reshaping reality everywhere, from dying coral reefs in Fiji to disappearing oases in Morocco and far, far beyond.

The role of our leaders: Writing at the end of 2020, Al Gore, the 45th vice president of the United States, found reasons for optimism in the Biden presidency, a feeling perhaps borne out by the passing of major climate legislation. That doesn’t mean there haven’t been criticisms. For example, Charles Harvey and Kurt House argue that subsidies for climate capture technology will ultimately be a waste.

The worst climate risks, mapped: In this feature, select a country, and we'll break down the climate hazards it faces. In the case of America, our maps, developed with experts, show where extreme heat is causing the most deaths.

What people can do: Justin Gillis and Hal Harvey describe the types of local activism that might be needed, while Saul Griffith points to how Australia shows the way on rooftop solar. Meanwhile, small changes at the office might be one good way to cut significant emissions, writes Carlos Gamarra.

How could this happen? A week later, it remains a meteorological mystery. Climate scientists have been noting for years the pattern of rapid intensification; a landmark 2017 paper was called “Will global warming make hurricane forecasting more difficult?” and new research on the subject, focused on North Atlantic hurricanes, was published just two weeks ago. But though Otis fits the general pattern, nothing about the conditions that gave rise to it seemed to raise the proper alarms in the conventional models. Local ocean temperatures were high, to be sure, but not crazily so. Low wind shear contributed, too, allowing the storm to gain strength somewhat undisturbed — but there, too, the metrics were not that unusual. The storm was relatively compact, which may have meant micro conditions were more important than more large-scale factors, which meteorologists tend to emphasize.

“Otis was the worst nightmare for forecasters,” says Kerry Emanuel, the author of that 2017 paper, whose own model, which isn’t included in the major ensemble projections, did show some chance of intensification — though not as sharp as what actually unfolded. “We used to say that the nightmare was that you go to bed with a tropical storm 36 hours from landfall and you wake up the next morning and it’s a Cat. 4 and you’ve got 12 hours left to evacuate. But what actually happened was worse than that imagined scenario: You woke up with a Cat. 5 and it was only a few hours from landfall. It’s a terrible tragedy,” he says. “I can’t imagine anything worse.”

For Emanuel, the key lesson from Otis is that we need to assess the possible course of storms probabilistically — understanding that, whatever the median projection for the intensity or course of a given hurricane, there is some chance of some low-likelihood, high-risk surprise. He also mentions a few variables that are not yet properly integrated into most forecasting tools — for instance, the relative salinity of the ocean surface and the way that it can affect the temperature gradients helping influence the intensity of a given storm. And over time, our models will surely improve, as modelers incorporate lessons from this hurricane and from the unprecedented environment in which it so spectacularly emerged.

Editors’ Picks

Why Can’t We Give Up the Ghosting?

How Music Can Be Mental Health Care

Pregnancy Is an Endurance Test. Why Not Train for It?

ADVERTISEMENT

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

But if the planet is in “uncharted territory,” as a concerned group of scientists emphasized in a global stocktaking published last week, this is one implication: a climate full of surprises. Out of 35 planetary “vital signs,” 20 “are now showing record extremes.” And while many of those vital signs have traced a linear trajectory upward, others have shown dramatic jumps this year — which is now almost certain to be the hottest year on record, despite being given a less than 10 percent chance by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration as recently as February.

Back then, most models predicted a global average temperature for 2023 somewhere between 1.1 and 1.2 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial average. We’ve now had five straight months above 1.4 degrees, and by year’s end the global average will likely approach, though probably not quite reach, 1.5 degrees. And the impact of a rising El Niño, which tends to push up global temperatures from a hot spot in the tropical Pacific, in addition to scrambling other aspects of the planet’s climate, has probably not yet peaked.

You can see local and regional impacts of these “gobsmackingly bananas” temperature anomalies almost everywhere you look, but perhaps nowhere more clearly than in the world’s oceans. As of a few weeks ago, nearly 80 percent of the world’s oceans were experiencing heat wave conditions, and as the climate scientist Daniel Swain points out, we have never observed the arrival of El Niño in waters anywhere near as warm as these. That isn’t to say we need to toss out our whole understanding of El Niño’s effect on global weather patterns, he tells me, but, particularly when it comes to second-order impacts brought about via temperature gradients in the ocean and other more distant “teleconnections” in the climate system, we should probably proceed with some humility, mindful that there are no perfect analogues for the meteorological conditions of the present.

The climate warnings of the last decades have given disasters, when they come, the sheen of the grimly expected. But a warming world will continue to shock, too — including perhaps tomorrow, when Storm Ciaran is expected to strike Europe, possibly the lowest-pressure event in the region in 200 years, a “bomb cyclone “now heading toward Europe powered by jet-stream winds moving at 200 miles per hour.

“There’s more happening to weather extremes now than can be explained by thermodynamics,” the climate scientist Stefan Rahmstorf wrote this week, adding, “we ain’t seen nothing yet.” “Think of a former once-in-5,000-year event which at 1.5° C of warming may have become a once-in-50-year event,” he warned in a paper published last month. “It will take many decades until we have seen all the possible extreme events a 1.5° C warmer world has in store for us.”

Climate warning like this won't stop Trudeau, Guilbeault, Wilkinson and

other climate warrior Liberals to continue giving out oil exploration and

drilling permits. Wilkinson our sneaky resource minister has lately reminded

oil producers to step up renewable energy development because demand

for oil will peak 7 years from now. It is just his way of saying he

wants oil supply growth to continue for another seven years and that

Trudeau's 50% emission reduction target by 2030 is BS.

other climate warrior Liberals to continue giving out oil exploration and

drilling permits. Wilkinson our sneaky resource minister has lately reminded

oil producers to step up renewable energy development because demand

for oil will peak 7 years from now. It is just his way of saying he

wants oil supply growth to continue for another seven years and that

Trudeau's 50% emission reduction target by 2030 is BS.

Today the debate is Hansen vs Mann.

Hansen says we're looking at about 5ºC warming and will hit 2ºC around 2030. That's towards extinction level change.

Mann says there are flaws in his work.

Hansen says we're looking at about 5ºC warming and will hit 2ºC around 2030. That's towards extinction level change.

Mann says there are flaws in his work.

Some excerpts from Hansen et al latest paper of Nov 2, 2023 for context. If a careful re-evaluation of published data leads M.E.M to diffferent conclusions that is entirely a healthy sign.

Energy, CO2 and the climate threat

The world’s energy and climate path has good reason: fossil fuels powered the industrial revolution and raised living standards. Fossil fuels still provide most of the world’s energy (Fig. 27a) and produce most CO2 emissions (Fig. 27b). Much of the world is still in early or middle stages of economic development. Energy is needed and fossil fuels are a convenient, affordable source of energy. One gallon (3.8 l) of gasoline (petrol) provides the work equivalent of more than 400 h labor by a healthy adult. These benefits are the basic reason for continued high emissions. The Covid pandemic dented emissions in 2020, but 2022 global emissions were a record high level. Fossil fuel emissions from mature economies are beginning to fall due to increasing energy efficiency, introduction of carbon-free energies, and export of manufacturing from mature economies to emerging economies. However, at least so far, those reductions have been more than offset by increasing emissions in developing nations (Fig. 28).

Figure 27.

![Global energy consumption and CO2 emissions (Hefner at al. [177] and Energy Institute [178]).](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/oocc/3/1/10.1093_oxfclm_kgad008/1/m_kgad008f27.jpeg?Expires=1702395722&Signature=RQvvyFpD60uQcaizCusGmeVHARkMjczNIBZd1yYyXCIxBfGp0oCZk2oHDeGqZ0UGCCZQzSUsxFiGF3wuyhOeGgNYbgK7WlfgwMikavFv45OM0zdMIwtVsMxdGrsXOYX38OgEhVd-2sz0g096LCq1ZACdhZsVSFc7xfs892S2TMQFREC2EmucsKZAzCD3IUddqApz5cKAUQlYwAgN4q8JwcToleQVxAFYgUo2O8~3N7-Q~DvQb-8Sr7wEFHlqtGU5yJHMksadjVR4GkCu2gkTLVYmgTCxuGcl5PGQcc03yT-wLPqAjfaQsTJhVrYGMYafK1qvvLXOukNLjd1r8gtCPg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Open in new tabDownload slide

Global energy consumption and CO2 emissions (Hefner at al. [177] and Energy Institute [178]).

Figure 28.

Open in new tabDownload slide

Fossil fuel CO2 emissions from mature and emerging economies. China is counted as an emerging economy. Data sources as in Fig. 27.

The potential for rising CO2 to be a serious threat to humanity was the reason for the 1979 Charney report, which confirmed that climate was likely sensitive to expected CO2 levels in the 21st century. In the 1980s it emerged that high climate sensitivity implied a long delay between changing atmospheric composition and the full climate response. Ice core data revealed the importance of amplifying climate feedbacks. A climate characterized by delayed response and amplifying feedbacks is especially dangerous because the public and policymakers are unlikely to make fundamental changes in world energy systems until they see visible evidence of the threat. Thus, it is incumbent on scientists to make this situation clear to the public as soon as possible. That task is complicated by the phenomenon of scientific reticence.

Scientific reticence

Bernard Barber decried the absence of attention to scientific reticence, a tendency of scientists to resist scientific discovery or new ideas [139]. Richard Feynman needled fellow physicists about their reticence to challenge authority [181], specifically to correct the electron charge that Millikan derived in his famous oil drop experiment. Later researchers moved Millikan’s result bit by bit—experimental uncertainties allow judgment—reaching an accurate result only after years. Their reticence embarrassed the physics community but caused no harm to society. A factor that may contribute to reticence among climate scientists is ‘delay discounting:’ preference for immediate over delayed rewards [182]. The penalty for ‘crying wolf’ is immediate, while the danger of being blamed for ‘fiddling while Rome was burning’ is distant. One of us has noted [183] that larding of papers and proposals with caveats and uncertainties increases chances of obtaining research support. ‘Gradualism’ that results from reticence is comfortable and well-suited for maintaining long-term support. Gradualism is apparent in IPCC’s history in evaluating climate sensitivity as summarized in our present paper. Barber identifies professional specialization—which causes ‘outsiders’ to be ignored by ‘insiders’—as one cause of reticence; specialization is relevant to ocean and ice sheet dynamics, matters upon which the future of young people hangs.

Discussion [184] with field glaciologists13 20 years ago revealed frustration with IPCC’s ice sheet assessment. One glaciologist said—about a photo [185] of a moulin (a vertical shaft that carries meltwater to the base of the Greenland ice sheet)—‘the whole ice sheet is going down that damned hole!’ Concern was based on observed ice sheet changes and paleoclimate evidence of sea level rise by several meters in a century, implying that ice sheet collapse is an exponential process. Thus, as an alternative to ice sheet models, we carried out a study described in Ice Melt [13]. In a GCM simulation, we added a growing freshwater flux to the ocean surface mixed layer around Greenland and Antarctica, with the flux in the early 21st century based on estimates from in situ glaciological studies [186] and satellite data on sea level trends near Antarctica [187]. Doubling times of 10 and 20 years were used for the growth of freshwater flux. One merit of our GCM was reduced, more realistic, small-scale ocean mixing, with a result that Antarctic Bottom Water formed close to the Antarctic coast [13], as in the real world. Growth of meltwater and GHG emissions led to shutdown of the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean overturning circulations, amplified warming at the foot of the ice shelves that buttress the ice sheets, and other feedbacks consistent with ‘nonlinearly growing sea level rise, reaching several meters in 50–150 years’ [13]. Shutdown of ocean overturning circulation occurs this century, as early as midcentury. The 50–150-year time scale for multimeter sea level rise is consistent with the 10–20-year range for ice melt doubling time. Real-world ice melt will not follow a smooth curve, but its growth rate is likely to accelerate in coming years due to increasing heat flux into the ocean (Fig. 25).

We submitted Ice Melt to a journal that makes reviews publicly available [188]. One reviewer, an IPCC lead author, seemed intent on blocking publication, while the other reviewer described the paper as a ‘masterwork of scholarly synthesis, modeling virtuosity, and insight, with profound implications’. Thus, the editor obtained additional reviewers, who recommended publication. Promptly, an indictment was published [189] of our conclusion that continued high GHG emissions would cause shutdown of the AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation) this century. The 15 authors, representing leading GCM groups, used 21 climate projections from eight ‘…state-of-the-science, IPCC class…’ GCMs to conclude that ‘…the probability of an AMOC collapse is negligible. This is contrary to a recent modeling study [Hansen et al., 2016] that used a much larger, and in our assessment unrealistic, Northern Hemisphere freshwater forcing… According to our probabilistic assessment, the likelihood of an AMOC collapse remains very small (<1% probability) if global warming is below ∼ 5K…’[189]. They treated the ensemble of their model results as if it were the probability distribution for the real world.

In contrast, we used paleoclimate evidence, global modeling, and ongoing climate observations. Paleoclimate data [190] showed that AMOC shutdown is not unusual and occurred in the Eemian (when global temperature was similar to today), and also that sea level in the Eemian rose a few meters within a century [191] with the likely source being collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet. Although we would not assert that our model corrected all excessive ocean mixing, the higher vertical resolution and improved mixing increased the sensitivity to freshwater flux, as confirmed in later tests [192]. Modern observations showed and continue to add evidence that the overturning Southern Ocean [193, 194] and North Atlantic [195] are already slowing. Growth of meltwater injection onto the Southern [196] and North Atlantic Oceans [197] is consistent with a doubling time of 10–20 years. High climate sensitivity inferred in our present paper also implies there will be a greater increase of precipitation on polar oceans than that in most climate models.

The indictment of Ice Melt by Bakker et al. [189] was accepted by the research community. Papers on the same topics ignored our paper or referred to it parenthetically with a note that we used unrealistic melt rates, even though these were based on observations. Ice Melt was blackballed in IPCC’s AR6 report, which is a form of censorship [14]. Science usually acknowledges alternative views and grants ultimate authority to nature. In the opinion of our first author, IPCC does not want its authority challenged and is comfortable with gradualism. Caution has merits, but the delayed response and amplifying feedbacks of climate make excessive reticence a danger. Our present paper—via revelation that the equilibrium response to current atmospheric composition is a nearly ice-free Antarctica—amplifies concern about locking in nonlinearly growing sea level rise. Also, our conclusion that CO2 was about 450 ppm at Antarctic glaciation disparages ice sheet models. Portions of the ice sheets may be recalcitrant to rapid change, but enough ice is in contact with the ocean to provide of the order of 25 m (80 feet) of sea level rise. Thus, if we allow a few meters of sea level rise, we may lock in much larger sea level rise.

Climate change responsibilities

The industrial revolution began in the U.K., which was the largest source of fossil fuel emissions in the 19th century (Fig. 29a), but development soon moved to Germany, the rest of Europe, and the U.S. Nearly half of global emissions were from the U.S. in the early 20th century, and the U.S. is presently the largest source of cumulative emissions (Fig. 29b) that drive climate change [198, 199]. Mature economies, mainly in the West, are responsible for most cumulative emissions, especially on a per capita basis (Fig. 30). Growth of emissions is now occurring in emerging economies (Figs 28 and 29a). China’s cumulative emissions will eventually pass those of the U.S. in the absence of a successful effort to replace coal with carbon-free energy.

Figure 29.

Open in new tabDownload slide

Fossil fuel CO2 emissions by nation or region as a fraction of global emissions. Data sources as in Fig. 27.

Figure 30.

![Cumulative per capita national fossil fuel emissions [200].](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/oocc/3/1/10.1093_oxfclm_kgad008/1/m_kgad008f30.jpeg?Expires=1702395722&Signature=I2FUbiaZ~zbmpYeJV3wlLiF6PiOFeYpnX5mR-P58dUxQ3ZL5GQGXnTFrvM0Rpp8JpiAYgsDjpM8LuSALY5k1WpyhODm-LujHt7ACkINvrLN7lpbM6lo3U24gSE1gEolDh32BU9-mDW-jhumGcjP67~XUaaDR7-c4-kyKxQ6u8MqcV-X2EY8yPxuc0f0SgQdNNgBJ5qMfr7mzGuyTI-jWxOV~rkJd5HLFSWIfYafM2NMNi21bhqY68Qze39Ncdk7lmotzX6r0GsA7YqKAUSrUmF7E3nXn5Ddj0LU2kY1PIb3F~g9Fk04Dkj2HIGq6r3Yx-b4FwWb81-veGKibShWV9A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Open in new tabDownload slide

Cumulative per capita national fossil fuel emissions [200].

Greenhouse gas emissions situation

The United Nations uses a target for maximum global warming to cajole progress in limiting climate change. The 2015 Paris Agreement [201] aimed to hold ‘the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above the pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above the pre-industrial levels.’ The IPCC AR5 report added a climate forcing scenario, RCP2.6, with a rapid decrease of GHG climate forcings, as needed to prevent global warming from exceeding 2°C. Since then, a gap between that scenario and reality opened and is growing (Fig. 31). The 0.03 W/m2 gap in 2022 could be closed by extracting CO2 from the air. However, required negative emissions (CO2 extracted from the air and stored permanently) must be larger than the desired atmospheric CO2 reduction by a factor of about 1.7 [63]. Thus, the required CO2 extraction is 2.1 ppm, which is 7.6 GtC. Based on a pilot direct-air carbon capture plant, Keith [202] estimates an extraction cost of $450–920 per tC, as clarified elsewhere [203]. Keith’s cost range yields an extraction cost of $3.4–7.0 trillion. That covers excess emissions in 2022 only; it is an annual cost. Given the difficulty the UN faced in raising $0.1 trillion for climate purposes and the growing emissions gap (Fig. 31), this example shows the need to reduce emissions as rapidly as practical and shows that carbon capture cannot be viewed as the solution, although it may play a role in a portfolio of policies, if its cost is driven down.

Figure 31.

![Annual growth of climate forcing by GHGs [38] including part of O3 forcing not included in CH4 forcing (Supplementary Material). MPTG and OTG are Montreal Protocol and Other Trace Gases.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/oocc/3/1/10.1093_oxfclm_kgad008/1/m_kgad008f31.jpeg?Expires=1702395722&Signature=bg9vaa8XDwYsbw9z2sJHr~ViwscgZWjIoD0P2AVFhfpHYIQkBOZgXlrrEPJZIgodIjWrs61jO0WME53rn0HzSce1hYKz2bXEt6oWiRzsNmlS6rxXcL~AtRuq6gk6W~gdbhnhwr7j0kYbg0sdoDJYiwqmdYi9AKMd~lg~PbvMQoTdmfhZtuIpi6VPuP4uhcIjvmAXcL0DxrH1FP3m96OxiCdPVVrWHLt5z6MZX4ok8oXSpg-3u5oiS85iF6CdrH-ImIpuISBHVbyu3TMcxyGs0QP0tn48i8FAUQ6pLqM-ZilR-UMkZXQFxZZ~gRk9J1oAJesXLWiJSBEUqDrYtveKig__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Open in new tabDownload slide

Annual growth of climate forcing by GHGs [38] including part of O3 forcing not included in CH4 forcing (Supplementary Material). MPTG and OTG are Montreal Protocol and Other Trace Gases.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), the scientific body advising the world on climate, has not bluntly informed the world that the present precatory policy approach will not keep warming below 1.5°C or even 2°C. The ‘tragedy of the commons’ [204] is that, as long as fossil fuel pollution can be dumped in the air free of charge, agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol [205] and Paris Agreement have limited effect on global emissions. Political leaders profess ambitions for dubious net-zero emissions while fossil fuel extraction expands. IPCC scenarios that phase down human-made climate change amount to ‘a miracle will occur’. The IPCC scenario that moves rapidly to negative global emissions (RCP2.6) has vast biomass-burning powerplants that capture and sequester CO2, a nature-ravaging, food-security-threatening [206], proposition without scientific and engineering credibility and without a realistic chance of being deployed at scale and on time to address the climate threat.

Climate and energy policy

Climate science reveals the threat of being too late. ‘Being too late’ refers not only to warning of the climate threat, but also to technical advice on policy implications. Are we scientists not complicit if we allow reticence and comfort to obfuscate our description of the climate situation? Does our training, years of graduate study and decades of experience, not make us well-equipped to advise the public on the climate situation and its policy implications? As professionals with deep understanding of planetary change and as guardians of young people and their future, do we not have an obligation, analogous to the code of ethics of medical professionals, to render to the public our full and unencumbered diagnosis? That is our objective.

The basis for the following opinions of the first author, to the extent not covered in this paper, will be described in a book in preparation [2]. We are in the early phase of a climate emergency. The present huge planetary energy imbalance assures that climate will become less tolerable to humanity, with greater climate extremes, before it is feasible to reverse the trend. Reversing the trend is essential—we must cool the planet—for the sake of preserving shorelines and saving the world’s coastal cities. Cooling will also address other major problems caused by global warming. We should aim to return to a climate like that in which civilization developed, in which the nature that we know and love thrived. As far as is known, it is still feasible to do that without passing through irreversible disasters such as many-meter sea level rise.

Abundant, affordable, carbon-free energy is essential to achieve a world with propitious climate, while recognizing the rights and aspirations of all people. The staggering magnitude of the task is implied by global and national carbon intensities: carbon emissions per unit energy use (Fig. 32). Global carbon intensity must decline to near zero over the next several decades. This chart—not vaporous promises of net zero future carbon emissions inserted in integrated assessment models—should guide realistic assessment of progress toward clean energy. Policy must include apolitical targeting of support for development of low-cost carbon-free energy. All nations would do well to study strategic decisions of Sweden, which led past decarbonization efforts (Fig. 32) and is likely to lead in the quest for zero or negative carbon intensity that will be needed to achieve a bright future for today’s young people and future generations.

Figure 32.

Open in new tabDownload slide

Carbon intensity (carbon emissions per unit energy use) of several nations and the world. Mtoe = megatons of oil equivalent. Data sources as in Fig. 27.

Given the global situation that we have allowed to develop, three actions are now essential.

First, underlying economic incentives must be installed globally to promote clean energy and discourage CO2 emissions. Thus, a rising price on GHG emissions is needed, enforced by border duties on products from nations without a carbon fee. Public buy-in and maximum efficacy require the funds to be distributed to the public, which will also address wealth disparity. Economists in the U.S. support carbon fee-and-dividend [207]; college and high school students join in advocacy [208]. A rising carbon price creates a level playing field for energy efficiency, renewable energy, nuclear power, and innovations; it would spur the thousands of ‘miracles’ needed for energy transition. However, instead, fossil fuels and renewable energy are now subsidized. Thus, nuclear energy has been disadvantaged and excluded as a ‘clean development mechanism’ under the Kyoto Protocol, based on myths about nuclear energy unsupported by scientific fact [209]. A rising carbon price is crucial for decarbonization, but not enough. Long-term planning is needed. Sweden provides an example: 50 years ago, its government decided to replace fossil fuel power stations with nuclear energy, which led to its extraordinary and rapid decarbonization (Fig. 32).

Second, global cooperation is needed. De facto cooperation between the West and China drove down the price of renewable energy. Without greater cooperation, developing nations will be the main source of future GHG emissions (Fig. 28). Carbon-free, dispatchable electricity is a crucial need. Nations with emerging economies are eager to have modern nuclear power because of its small environmental footprint. China-U.S. cooperation to develop low-cost nuclear power was proposed, but stymied by U.S. prohibition of technology transfer [210]. Competition is normal, but it can be managed if there is a will, reaping benefits of cooperation over confrontation [211]. Of late, priority has been given instead to economic and military hegemony, despite recognition of the climate threat, and without consultation with young people or seeming consideration of their aspirations. Scientists can support an ecumenical perspective of our shared future by expanding international cooperation. Awareness of the gathering climate storm will grow this decade, so we must increase scientific understanding worldwide as needed for climate restoration.

Third, we must take action to reduce and reverse Earth’s energy imbalance. Highest priority is to phase down emissions, but it is no longer feasible to rapidly restore energy balance via only GHG emission reductions. Additional action is almost surely needed to prevent grievous escalation of climate impacts including lock-in of sea level rise that could destroy coastal cities world-wide. At least several years will be needed to define and gain acceptance of an approach for climate restoration. This effort should not deter action on mitigation of emissions; on the contrary, the concept of human intervention in climate is distasteful to many people, so support for GHG emission reductions will likely increase. Temporary solar radiation management (SRM) will probably be needed, e.g. via purposeful injection of atmospheric aerosols. Risks of such intervention must be defined, as well as risks of no intervention; thus, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences recommends research on SRM [212]. The Mt. Pinatubo eruption of 1991 is a natural experiment [213, 214] with a forcing that reached [30] –3 W/m2. Pinatubo deserves a coordinated study with current models. The most innocuous aerosols may be fine salty droplets extracted from the ocean and sprayed into the air by autonomous sailboats [215]. This approach has been discussed for potential use on a global scale [216], but it needs research into potential unintended effects [217]. This decade may be our last chance to develop the knowledge, technical capability, and political will for actions needed to save global coastal regions from long-term inundation.

Politics and climate change

Actions needed to drive carbon intensity to zero—most important a rising carbon fee—are feasible, but not happening. The first author gained perspective on the reasons why during trips to Washington, DC, and to other nations at the invitation of governments, environmentalists, and, in one case, oil executives in London. Politicians from right (conservative) and left (progressive) parties are affected by fossil fuel interests. The right denies that fossil fuels cause climate change or says that the effect is exaggerated. The left takes up the climate cause but proposes actions with only modest effect, such as cap-and-trade with offsets, including giveaways to the fossil fuel industry. The left also points to work of Amory Lovins as showing that energy efficiency plus renewables (mainly wind and solar energy) are sufficient to phase out fossil fuels. Lovins says that nuclear power is not needed. It is no wonder that the President of Shell Oil would write a foreword with praise for Lovins’ book, Reinventing Fire [218], and that the oil executives in London did not see Lovins’ work as a threat to their business.

Opportunities for progress often occur in conjunction with crises. Today, the world faces a crisis—political polarization, especially in the United States—that threatens effective governance. Yet the crisis offers an opportunity for young people to help shape the future of the nation and the planet. Ideals professed by the United States at the end of World War II were consummated in formation of the United Nations, the World Bank, the Marshall Plan, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Progress toward equal rights continued, albeit slowly. The ‘American dream’ of economic opportunity was real, as most people willing to work hard could afford college. Immigration policy welcomed the brightest; NASA in the 1960s invited scientists from European countries, Japan, China, India, Canada, and those wanting to stay found immigration to be straightforward. But the power of special interests in Washington grew, government became insular and inefficient, and Congress refused to police itself. Their first priority became reelection and maintenance of elite status, supported by special interests. Thousands of pages of giveaways to special interests lard every funding bill, including the climate bill titled ‘Inflation Reduction Act’—Orwellian double-speak—as the funding is borrowed from young people via deficit spending. The public is fed up with the Washington swamp but hamstrung by rigid two-party elections focused on a polarized cultural war.

A political party that takes no money from special interests is essential to address political polarization, which is necessary if the West is to be capable of helping preserve the planet and a bright future for coming generations. Young people showed their ability to drive an election—via their support of Barack Obama in 2008 and Bernie Sanders in 2016—without any funding from special interests. Groundwork is being laid to allow third party candidates in 2026 and 2028 elections in the U.S. Ranked voting is being advocated in every state to avoid the ‘spoiler’ effect of a third party. It is asking a lot to expect young people to grasp the situation that they have been handed—but a lot is at stake. As they realize that they are being handed a planet in decline, the first reaction may be to stamp their feet and demand that governments do better, but that has little effect. Nor is it sufficient to parrot big environmental organizations, which are now part of the problem, as they are partly supported by the fossil fuel industry and wealthy donors who are comfortable with the status quo. Instead, young people have the opportunity to provide the drive for a revolutionary third party that restores democratic ideals while developing the technical knowledge that is needed to navigate the stormy sea that their world is setting out upon.

Energy, CO2 and the climate threat

The world’s energy and climate path has good reason: fossil fuels powered the industrial revolution and raised living standards. Fossil fuels still provide most of the world’s energy (Fig. 27a) and produce most CO2 emissions (Fig. 27b). Much of the world is still in early or middle stages of economic development. Energy is needed and fossil fuels are a convenient, affordable source of energy. One gallon (3.8 l) of gasoline (petrol) provides the work equivalent of more than 400 h labor by a healthy adult. These benefits are the basic reason for continued high emissions. The Covid pandemic dented emissions in 2020, but 2022 global emissions were a record high level. Fossil fuel emissions from mature economies are beginning to fall due to increasing energy efficiency, introduction of carbon-free energies, and export of manufacturing from mature economies to emerging economies. However, at least so far, those reductions have been more than offset by increasing emissions in developing nations (Fig. 28).

Figure 27.

![Global energy consumption and CO2 emissions (Hefner at al. [177] and Energy Institute [178]).](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/oocc/3/1/10.1093_oxfclm_kgad008/1/m_kgad008f27.jpeg?Expires=1702395722&Signature=RQvvyFpD60uQcaizCusGmeVHARkMjczNIBZd1yYyXCIxBfGp0oCZk2oHDeGqZ0UGCCZQzSUsxFiGF3wuyhOeGgNYbgK7WlfgwMikavFv45OM0zdMIwtVsMxdGrsXOYX38OgEhVd-2sz0g096LCq1ZACdhZsVSFc7xfs892S2TMQFREC2EmucsKZAzCD3IUddqApz5cKAUQlYwAgN4q8JwcToleQVxAFYgUo2O8~3N7-Q~DvQb-8Sr7wEFHlqtGU5yJHMksadjVR4GkCu2gkTLVYmgTCxuGcl5PGQcc03yT-wLPqAjfaQsTJhVrYGMYafK1qvvLXOukNLjd1r8gtCPg__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Open in new tabDownload slide

Global energy consumption and CO2 emissions (Hefner at al. [177] and Energy Institute [178]).

Figure 28.

Open in new tabDownload slide

Fossil fuel CO2 emissions from mature and emerging economies. China is counted as an emerging economy. Data sources as in Fig. 27.

The potential for rising CO2 to be a serious threat to humanity was the reason for the 1979 Charney report, which confirmed that climate was likely sensitive to expected CO2 levels in the 21st century. In the 1980s it emerged that high climate sensitivity implied a long delay between changing atmospheric composition and the full climate response. Ice core data revealed the importance of amplifying climate feedbacks. A climate characterized by delayed response and amplifying feedbacks is especially dangerous because the public and policymakers are unlikely to make fundamental changes in world energy systems until they see visible evidence of the threat. Thus, it is incumbent on scientists to make this situation clear to the public as soon as possible. That task is complicated by the phenomenon of scientific reticence.

Scientific reticence

Bernard Barber decried the absence of attention to scientific reticence, a tendency of scientists to resist scientific discovery or new ideas [139]. Richard Feynman needled fellow physicists about their reticence to challenge authority [181], specifically to correct the electron charge that Millikan derived in his famous oil drop experiment. Later researchers moved Millikan’s result bit by bit—experimental uncertainties allow judgment—reaching an accurate result only after years. Their reticence embarrassed the physics community but caused no harm to society. A factor that may contribute to reticence among climate scientists is ‘delay discounting:’ preference for immediate over delayed rewards [182]. The penalty for ‘crying wolf’ is immediate, while the danger of being blamed for ‘fiddling while Rome was burning’ is distant. One of us has noted [183] that larding of papers and proposals with caveats and uncertainties increases chances of obtaining research support. ‘Gradualism’ that results from reticence is comfortable and well-suited for maintaining long-term support. Gradualism is apparent in IPCC’s history in evaluating climate sensitivity as summarized in our present paper. Barber identifies professional specialization—which causes ‘outsiders’ to be ignored by ‘insiders’—as one cause of reticence; specialization is relevant to ocean and ice sheet dynamics, matters upon which the future of young people hangs.

Discussion [184] with field glaciologists13 20 years ago revealed frustration with IPCC’s ice sheet assessment. One glaciologist said—about a photo [185] of a moulin (a vertical shaft that carries meltwater to the base of the Greenland ice sheet)—‘the whole ice sheet is going down that damned hole!’ Concern was based on observed ice sheet changes and paleoclimate evidence of sea level rise by several meters in a century, implying that ice sheet collapse is an exponential process. Thus, as an alternative to ice sheet models, we carried out a study described in Ice Melt [13]. In a GCM simulation, we added a growing freshwater flux to the ocean surface mixed layer around Greenland and Antarctica, with the flux in the early 21st century based on estimates from in situ glaciological studies [186] and satellite data on sea level trends near Antarctica [187]. Doubling times of 10 and 20 years were used for the growth of freshwater flux. One merit of our GCM was reduced, more realistic, small-scale ocean mixing, with a result that Antarctic Bottom Water formed close to the Antarctic coast [13], as in the real world. Growth of meltwater and GHG emissions led to shutdown of the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean overturning circulations, amplified warming at the foot of the ice shelves that buttress the ice sheets, and other feedbacks consistent with ‘nonlinearly growing sea level rise, reaching several meters in 50–150 years’ [13]. Shutdown of ocean overturning circulation occurs this century, as early as midcentury. The 50–150-year time scale for multimeter sea level rise is consistent with the 10–20-year range for ice melt doubling time. Real-world ice melt will not follow a smooth curve, but its growth rate is likely to accelerate in coming years due to increasing heat flux into the ocean (Fig. 25).

We submitted Ice Melt to a journal that makes reviews publicly available [188]. One reviewer, an IPCC lead author, seemed intent on blocking publication, while the other reviewer described the paper as a ‘masterwork of scholarly synthesis, modeling virtuosity, and insight, with profound implications’. Thus, the editor obtained additional reviewers, who recommended publication. Promptly, an indictment was published [189] of our conclusion that continued high GHG emissions would cause shutdown of the AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation) this century. The 15 authors, representing leading GCM groups, used 21 climate projections from eight ‘…state-of-the-science, IPCC class…’ GCMs to conclude that ‘…the probability of an AMOC collapse is negligible. This is contrary to a recent modeling study [Hansen et al., 2016] that used a much larger, and in our assessment unrealistic, Northern Hemisphere freshwater forcing… According to our probabilistic assessment, the likelihood of an AMOC collapse remains very small (<1% probability) if global warming is below ∼ 5K…’[189]. They treated the ensemble of their model results as if it were the probability distribution for the real world.

In contrast, we used paleoclimate evidence, global modeling, and ongoing climate observations. Paleoclimate data [190] showed that AMOC shutdown is not unusual and occurred in the Eemian (when global temperature was similar to today), and also that sea level in the Eemian rose a few meters within a century [191] with the likely source being collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet. Although we would not assert that our model corrected all excessive ocean mixing, the higher vertical resolution and improved mixing increased the sensitivity to freshwater flux, as confirmed in later tests [192]. Modern observations showed and continue to add evidence that the overturning Southern Ocean [193, 194] and North Atlantic [195] are already slowing. Growth of meltwater injection onto the Southern [196] and North Atlantic Oceans [197] is consistent with a doubling time of 10–20 years. High climate sensitivity inferred in our present paper also implies there will be a greater increase of precipitation on polar oceans than that in most climate models.

The indictment of Ice Melt by Bakker et al. [189] was accepted by the research community. Papers on the same topics ignored our paper or referred to it parenthetically with a note that we used unrealistic melt rates, even though these were based on observations. Ice Melt was blackballed in IPCC’s AR6 report, which is a form of censorship [14]. Science usually acknowledges alternative views and grants ultimate authority to nature. In the opinion of our first author, IPCC does not want its authority challenged and is comfortable with gradualism. Caution has merits, but the delayed response and amplifying feedbacks of climate make excessive reticence a danger. Our present paper—via revelation that the equilibrium response to current atmospheric composition is a nearly ice-free Antarctica—amplifies concern about locking in nonlinearly growing sea level rise. Also, our conclusion that CO2 was about 450 ppm at Antarctic glaciation disparages ice sheet models. Portions of the ice sheets may be recalcitrant to rapid change, but enough ice is in contact with the ocean to provide of the order of 25 m (80 feet) of sea level rise. Thus, if we allow a few meters of sea level rise, we may lock in much larger sea level rise.

Climate change responsibilities

The industrial revolution began in the U.K., which was the largest source of fossil fuel emissions in the 19th century (Fig. 29a), but development soon moved to Germany, the rest of Europe, and the U.S. Nearly half of global emissions were from the U.S. in the early 20th century, and the U.S. is presently the largest source of cumulative emissions (Fig. 29b) that drive climate change [198, 199]. Mature economies, mainly in the West, are responsible for most cumulative emissions, especially on a per capita basis (Fig. 30). Growth of emissions is now occurring in emerging economies (Figs 28 and 29a). China’s cumulative emissions will eventually pass those of the U.S. in the absence of a successful effort to replace coal with carbon-free energy.

Figure 29.

Open in new tabDownload slide

Fossil fuel CO2 emissions by nation or region as a fraction of global emissions. Data sources as in Fig. 27.

Figure 30.

![Cumulative per capita national fossil fuel emissions [200].](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/oocc/3/1/10.1093_oxfclm_kgad008/1/m_kgad008f30.jpeg?Expires=1702395722&Signature=I2FUbiaZ~zbmpYeJV3wlLiF6PiOFeYpnX5mR-P58dUxQ3ZL5GQGXnTFrvM0Rpp8JpiAYgsDjpM8LuSALY5k1WpyhODm-LujHt7ACkINvrLN7lpbM6lo3U24gSE1gEolDh32BU9-mDW-jhumGcjP67~XUaaDR7-c4-kyKxQ6u8MqcV-X2EY8yPxuc0f0SgQdNNgBJ5qMfr7mzGuyTI-jWxOV~rkJd5HLFSWIfYafM2NMNi21bhqY68Qze39Ncdk7lmotzX6r0GsA7YqKAUSrUmF7E3nXn5Ddj0LU2kY1PIb3F~g9Fk04Dkj2HIGq6r3Yx-b4FwWb81-veGKibShWV9A__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Open in new tabDownload slide

Cumulative per capita national fossil fuel emissions [200].

Greenhouse gas emissions situation

The United Nations uses a target for maximum global warming to cajole progress in limiting climate change. The 2015 Paris Agreement [201] aimed to hold ‘the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above the pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above the pre-industrial levels.’ The IPCC AR5 report added a climate forcing scenario, RCP2.6, with a rapid decrease of GHG climate forcings, as needed to prevent global warming from exceeding 2°C. Since then, a gap between that scenario and reality opened and is growing (Fig. 31). The 0.03 W/m2 gap in 2022 could be closed by extracting CO2 from the air. However, required negative emissions (CO2 extracted from the air and stored permanently) must be larger than the desired atmospheric CO2 reduction by a factor of about 1.7 [63]. Thus, the required CO2 extraction is 2.1 ppm, which is 7.6 GtC. Based on a pilot direct-air carbon capture plant, Keith [202] estimates an extraction cost of $450–920 per tC, as clarified elsewhere [203]. Keith’s cost range yields an extraction cost of $3.4–7.0 trillion. That covers excess emissions in 2022 only; it is an annual cost. Given the difficulty the UN faced in raising $0.1 trillion for climate purposes and the growing emissions gap (Fig. 31), this example shows the need to reduce emissions as rapidly as practical and shows that carbon capture cannot be viewed as the solution, although it may play a role in a portfolio of policies, if its cost is driven down.

Figure 31.

![Annual growth of climate forcing by GHGs [38] including part of O3 forcing not included in CH4 forcing (Supplementary Material). MPTG and OTG are Montreal Protocol and Other Trace Gases.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/oocc/3/1/10.1093_oxfclm_kgad008/1/m_kgad008f31.jpeg?Expires=1702395722&Signature=bg9vaa8XDwYsbw9z2sJHr~ViwscgZWjIoD0P2AVFhfpHYIQkBOZgXlrrEPJZIgodIjWrs61jO0WME53rn0HzSce1hYKz2bXEt6oWiRzsNmlS6rxXcL~AtRuq6gk6W~gdbhnhwr7j0kYbg0sdoDJYiwqmdYi9AKMd~lg~PbvMQoTdmfhZtuIpi6VPuP4uhcIjvmAXcL0DxrH1FP3m96OxiCdPVVrWHLt5z6MZX4ok8oXSpg-3u5oiS85iF6CdrH-ImIpuISBHVbyu3TMcxyGs0QP0tn48i8FAUQ6pLqM-ZilR-UMkZXQFxZZ~gRk9J1oAJesXLWiJSBEUqDrYtveKig__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

Open in new tabDownload slide

Annual growth of climate forcing by GHGs [38] including part of O3 forcing not included in CH4 forcing (Supplementary Material). MPTG and OTG are Montreal Protocol and Other Trace Gases.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), the scientific body advising the world on climate, has not bluntly informed the world that the present precatory policy approach will not keep warming below 1.5°C or even 2°C. The ‘tragedy of the commons’ [204] is that, as long as fossil fuel pollution can be dumped in the air free of charge, agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol [205] and Paris Agreement have limited effect on global emissions. Political leaders profess ambitions for dubious net-zero emissions while fossil fuel extraction expands. IPCC scenarios that phase down human-made climate change amount to ‘a miracle will occur’. The IPCC scenario that moves rapidly to negative global emissions (RCP2.6) has vast biomass-burning powerplants that capture and sequester CO2, a nature-ravaging, food-security-threatening [206], proposition without scientific and engineering credibility and without a realistic chance of being deployed at scale and on time to address the climate threat.

Climate and energy policy

Climate science reveals the threat of being too late. ‘Being too late’ refers not only to warning of the climate threat, but also to technical advice on policy implications. Are we scientists not complicit if we allow reticence and comfort to obfuscate our description of the climate situation? Does our training, years of graduate study and decades of experience, not make us well-equipped to advise the public on the climate situation and its policy implications? As professionals with deep understanding of planetary change and as guardians of young people and their future, do we not have an obligation, analogous to the code of ethics of medical professionals, to render to the public our full and unencumbered diagnosis? That is our objective.

The basis for the following opinions of the first author, to the extent not covered in this paper, will be described in a book in preparation [2]. We are in the early phase of a climate emergency. The present huge planetary energy imbalance assures that climate will become less tolerable to humanity, with greater climate extremes, before it is feasible to reverse the trend. Reversing the trend is essential—we must cool the planet—for the sake of preserving shorelines and saving the world’s coastal cities. Cooling will also address other major problems caused by global warming. We should aim to return to a climate like that in which civilization developed, in which the nature that we know and love thrived. As far as is known, it is still feasible to do that without passing through irreversible disasters such as many-meter sea level rise.

Abundant, affordable, carbon-free energy is essential to achieve a world with propitious climate, while recognizing the rights and aspirations of all people. The staggering magnitude of the task is implied by global and national carbon intensities: carbon emissions per unit energy use (Fig. 32). Global carbon intensity must decline to near zero over the next several decades. This chart—not vaporous promises of net zero future carbon emissions inserted in integrated assessment models—should guide realistic assessment of progress toward clean energy. Policy must include apolitical targeting of support for development of low-cost carbon-free energy. All nations would do well to study strategic decisions of Sweden, which led past decarbonization efforts (Fig. 32) and is likely to lead in the quest for zero or negative carbon intensity that will be needed to achieve a bright future for today’s young people and future generations.

Figure 32.

Open in new tabDownload slide

Carbon intensity (carbon emissions per unit energy use) of several nations and the world. Mtoe = megatons of oil equivalent. Data sources as in Fig. 27.

Given the global situation that we have allowed to develop, three actions are now essential.

First, underlying economic incentives must be installed globally to promote clean energy and discourage CO2 emissions. Thus, a rising price on GHG emissions is needed, enforced by border duties on products from nations without a carbon fee. Public buy-in and maximum efficacy require the funds to be distributed to the public, which will also address wealth disparity. Economists in the U.S. support carbon fee-and-dividend [207]; college and high school students join in advocacy [208]. A rising carbon price creates a level playing field for energy efficiency, renewable energy, nuclear power, and innovations; it would spur the thousands of ‘miracles’ needed for energy transition. However, instead, fossil fuels and renewable energy are now subsidized. Thus, nuclear energy has been disadvantaged and excluded as a ‘clean development mechanism’ under the Kyoto Protocol, based on myths about nuclear energy unsupported by scientific fact [209]. A rising carbon price is crucial for decarbonization, but not enough. Long-term planning is needed. Sweden provides an example: 50 years ago, its government decided to replace fossil fuel power stations with nuclear energy, which led to its extraordinary and rapid decarbonization (Fig. 32).

Second, global cooperation is needed. De facto cooperation between the West and China drove down the price of renewable energy. Without greater cooperation, developing nations will be the main source of future GHG emissions (Fig. 28). Carbon-free, dispatchable electricity is a crucial need. Nations with emerging economies are eager to have modern nuclear power because of its small environmental footprint. China-U.S. cooperation to develop low-cost nuclear power was proposed, but stymied by U.S. prohibition of technology transfer [210]. Competition is normal, but it can be managed if there is a will, reaping benefits of cooperation over confrontation [211]. Of late, priority has been given instead to economic and military hegemony, despite recognition of the climate threat, and without consultation with young people or seeming consideration of their aspirations. Scientists can support an ecumenical perspective of our shared future by expanding international cooperation. Awareness of the gathering climate storm will grow this decade, so we must increase scientific understanding worldwide as needed for climate restoration.

Third, we must take action to reduce and reverse Earth’s energy imbalance. Highest priority is to phase down emissions, but it is no longer feasible to rapidly restore energy balance via only GHG emission reductions. Additional action is almost surely needed to prevent grievous escalation of climate impacts including lock-in of sea level rise that could destroy coastal cities world-wide. At least several years will be needed to define and gain acceptance of an approach for climate restoration. This effort should not deter action on mitigation of emissions; on the contrary, the concept of human intervention in climate is distasteful to many people, so support for GHG emission reductions will likely increase. Temporary solar radiation management (SRM) will probably be needed, e.g. via purposeful injection of atmospheric aerosols. Risks of such intervention must be defined, as well as risks of no intervention; thus, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences recommends research on SRM [212]. The Mt. Pinatubo eruption of 1991 is a natural experiment [213, 214] with a forcing that reached [30] –3 W/m2. Pinatubo deserves a coordinated study with current models. The most innocuous aerosols may be fine salty droplets extracted from the ocean and sprayed into the air by autonomous sailboats [215]. This approach has been discussed for potential use on a global scale [216], but it needs research into potential unintended effects [217]. This decade may be our last chance to develop the knowledge, technical capability, and political will for actions needed to save global coastal regions from long-term inundation.

Politics and climate change

Actions needed to drive carbon intensity to zero—most important a rising carbon fee—are feasible, but not happening. The first author gained perspective on the reasons why during trips to Washington, DC, and to other nations at the invitation of governments, environmentalists, and, in one case, oil executives in London. Politicians from right (conservative) and left (progressive) parties are affected by fossil fuel interests. The right denies that fossil fuels cause climate change or says that the effect is exaggerated. The left takes up the climate cause but proposes actions with only modest effect, such as cap-and-trade with offsets, including giveaways to the fossil fuel industry. The left also points to work of Amory Lovins as showing that energy efficiency plus renewables (mainly wind and solar energy) are sufficient to phase out fossil fuels. Lovins says that nuclear power is not needed. It is no wonder that the President of Shell Oil would write a foreword with praise for Lovins’ book, Reinventing Fire [218], and that the oil executives in London did not see Lovins’ work as a threat to their business.