Zionism cannot produce a just peace. Only external pressure can end the Israeli apartheid.

I grew up in a Zionist household, spent 12 years in

a Zionist youth movement, lived for four years in Israel, and have friends and family who served in the Israeli Defense Forces. When that is your world, it’s hard to see apartheid as it’s happening in front of you.

I grew up in France, in a Jewish community where unconditional love and support for Israel were the norm. The term Zionism, the movement for the establishment and support of a Jewish state in present-day Palestine, wasn’t even used because that’s all we knew. Jews had been nearly wiped out by pogroms and repeated holocausts, and a Jewish state was the only way to keep us safe. Antisemitism wasn’t just a fact of history; we all experienced it in our daily lives.

Zionism is rooted in trauma and fear. It’s about survival and love for the Jewish people. But like any other ethnic nationalism, Zionism establishes a hierarchy: It’s about prioritizing our safety and well-being, even at the expense of others. It relies on an alternate historical narrative that justifies the occupation and rationalizes the status quo. And it cannot produce a just peace on its own.

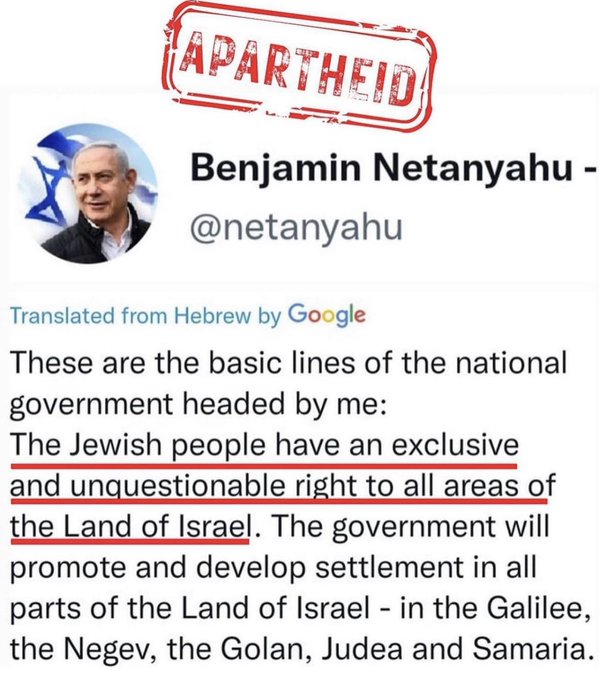

The Israeli occupation of the West Bank is,

by every definition, apartheid: two legal systems for two ethnic groups. If a Jew and an Arab commit the exact same crime in the West Bank, the Jew will face a civil court; the Arab, a military court. But most Israelis can’t fathom this as unjust. They fight the term “apartheid” because they genuinely believe that the discrimination is legitimate and a matter of self-defense.

My Jewish community was fed a historical narrative divorced from reality: That Palestine was a largely uninhabited piece of desert before we settled it. That during what we call Israel’s War of Independence, Palestinians were not expelled by Jewish militias but instead willingly left their homes to make room for Arab armies to “

push all the Jews into the sea, dead or alive.” That Arab leaders were never interested in compromising, turning down peace offers from Israel and the United States one after the other. The list goes on.

Those assertions have long been debunked — for example, by a former Israeli prime minister

recounting his rolein expelling Palestinians during the 1948 war, and by historians showing that most of the land in Palestine was cultivated by Arab farmers before Zionist migration. But when your entire world buys into that narrative — friends and family, the media you consume, the organizations you join and, if you grow up in Israel, your educational system — that is your reality. It’s a false one, disconnected from historical facts, but it is yours.

Compounding this alternate reality are

more than a hundred years of conflict that have dehumanized Palestinians in the eyes of Israeli Jews. When the IDF

bombs Gaza and kills large numbers of civilians, including children, Israelis think that Palestinians should blame themselves: because they didn’t accept past peace offers, because they tolerate armed groups in their midst, because they “teach their children to hate Jews.” We tell ourselves that at the end of the day, Israel is merely defending itself and that there is simply no alternative.

The same thought process justifies the Gaza blockade, the military checkpoints in the West Bank, the separation wall and the bulldozing of homes in Palestinian communities. Palestinians’ pain is either fake or self-inflicted; it is not as real as ours.

Of course, some Israelis reject these narratives and actively campaign for Palestinian liberation. But those make up a minority. The average Israeli doesn’t contend with what it means to live out an occupation on a daily basis: having to submit to foreign troops at checkpoints, requiring a permit for any and all matters from a government that doesn’t represent you, knowing that soldiers can invade your home or seize your property with no accountability.

The only thing that can bring about Palestinian liberation is if the cost of the occupation begins to outweigh its benefits to Israel. That would require, as it did for other apartheids and occupations, massive external pressure. In South Africa, international sanctions, an arms embargo and a global boycott forced the collapse of the racist regime. The brutal occupation of East Timor by Indonesia was ended by a global solidarity movement and international pressure. In the American South, it was legislation and Supreme Court decisions that imposed equal rights and ended the racial segregation of Jim Crow.

In all those cases, the dominant group was so entrenched in its own historical narrative and so disconnected from the humanity of their “enemies” that only outside coercion could move them to a just solution. This is true of Israel as well.

To end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, that coercion could take the form of consumer boycott of Israeli goods, corporate boycotts of Israeli technology, and sanctions by Israel’s main trade partners and political supporters, the United States and the European Union.

An apartheid state will not willingly change itself. Outside measures are the only ones that can meaningfully push Israel toward ending the occupation.