Arlington Cemetery website drops links for Black, Hispanic, and women veterans

The Arlington National Cemetery website "unpublished" links to material about Black, Hispanic and women veterans.

Arlington National Cemetery is the most venerated final resting ground in the nation, overseen by silent soldiers in immaculate uniforms with ramrod-straight discipline. Across its hundreds of acres in Virginia, they watch over 400,000 graves of U.S. service members dating back to the Civil War, including two presidents, and more than 400 Medal of Honor recipients.

But in recent weeks, the cemetery’s public website has scrubbed dozens of pages on gravesites and educational materials that include histories of prominent Black, Hispanic and female service members buried in the cemetery, along with educational material on dozens of Medal of Honor recipients and maps of prominent gravesites of Marine Corps veterans and other services.

Cemetery officials confirmed to Task & Purpose that the pages were “unpublished” to meet recent orders by President Donald Trump and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth targeting race and gender-related language and policies in the military.

Gone from public view are links to lists of dozens of “Notable Graves” at Arlington of women and Black and Hispanic service members who are buried in the cemetery. About a dozen other “Notable Graves” lists remain highlighted on the website, including lists of politicians, athletes and even foreign nationals.

Also gone are dozens of academic lesson plans — some built for classroom use, others as self-guided walking tours — on Arlington’s history and those interred there. Among the documents removed or hidden from the cemetery’s “Education” section are maps and notes for self-guided walking tours to the graves of dozens of Medal of Honor recipients and other maps to notable gravesites for war heroes from each military service. Why information on recipients of the Medal of Honor — the nation’s highest award for combat valor — would be removed is unclear, but three of the service members whose graves were noted in the lessons were awarded the Medal of Honor decades after their combat actions following formal Pentagon reviews that determined they had been denied the award on racial grounds.

Like the “Notable Graves” lists, some of the lesson plans remain live but ‘walled-off’ on the cemetery’s website, with no way to reach them through links on the site. Task & Purpose located the de-linked pages by copying the original URL addresses from archived pages at Archive.org or by searching specifically for the pages on Google, which still lists them.

On at least one page that can still be accessed on search engines, language referring to civil rights or racial issues in the military appears to have been altered. A page on Black soldiers in World War II read in December that they had “served their country and fought for racial justice” but now only notes that memorials in the cemetery “honor their dedication and service.”

A spokesperson at Arlington National Cemetery — which is operated by the Army under the Army Office of Cemeteries — confirmed that the pages had been delisted or “unpublished” but insisted that the academic modules would be republished after they are “reviewed and updated.” The spokesperson said no schedule for their return could be provided.

“The Army has taken immediate steps to comply with all executive orders related to diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) personnel, programs, and policies,” an Army spokesperson at Arlington told Task & Purpose. “The Army will continue to review its personnel, policies, and programs to ensure it remains in compliance with law and presidential orders. Social media and web pages were removed, archived, or changed to avoid noncompliance with executive orders.”

As of March 12, the three original “Notable Graves” lists and the dozens of educational pages appear to still be posted on Arlington’s military domain — arlingtoncemetery.mil — as webpages. Some can be accessed on the cemetery’s website by tracing a multi-click trail of embedded links on other still-public pages. It was unclear if those ‘backdoor’ paths to the pages were left intentionally or were overlooked when the main links to the unpublished pages were removed.

A censorship ‘shitshow’

The removal of the academic lessons hit hard for Civil War historian Kevin Levin, who first noted that Arlington had removed the pages on his substack newsletter. Levin lectures and writes on Civil War history and each year leads trips of history teachers — mostly high school and middle school teachers — through Arlington, so they can better teach students about the cemetery.

Levin noticed that the lessons were missing, he told Task & Purpose, when a teacher he works with tried to prepare a lesson for her students.

“One of the teachers went online and couldn’t find the pages, so that’s when she contacted me,” Levin said. He compared the wholesale removal of entire lesson plans to the recent revelation that photos of the first bomber to drop an atomic bomb had reportedly been marked for removal from a Pentagon photo archive. “I don’t know who did it. If we’re talking about one of these, low-level [Department of Government Efficiency] people or whatever, who has just been given a list of key terms, yeah, kind of the Enola Gay situation, right? It’s got ‘gay’ in it, so we have to delete it, right?”

A photo of Arlington National Cemetery’s Section 27. Army photo.

Levin said Arlington’s own historians often accompany his group’s trips.

“I know the historians and the educators at Arlington, because they meet with our staff every year, and they’ve done a great job of creating lesson plans, they go out of their way to meet with teachers. And I know for a fact that a lot of our teachers are using these lesson plans,” Levin said. “I get the sense that this is being carried out in the sloppiest manner. I get the sense that we’re talking about people who are setting up algorithms and are looking for certain things. I don’t know if this is the end of it. I don’t think it is, I just don’t think these people, whoever is responsible, really knows what they’re doing.”

Levin said he hesitated to post about the missing documents because public exposure could reflect poorly on the professional historians who work at the cemetery and who are “exactly what you want from a federal agency that is responsible for interpreting the past.”

But the slash-and-burn approach to the website, he said, was too much.

“I’ll put it bluntly, this is a shitshow,” he said. “And this one hit home, so I did what I did.”

What’s missing from Arlington’s website

Task & Purpose compared Arlington website pages available on March 12 to copies preserved on Archive.org in December and early January. Between those dates, several web pages appear to have been walled off from public view on the main Army-run Arlington website, though not fully deleted. They are:

- Three lists of “Notable Graves” that highlight several dozen gravesites of notable Black, Hispanic and female service members and public figures buried in Arlington. The pages list the location of graves in the cemetery and provide a one-paragraph biography of each person. The pages that host the three lists are still on the website but have been removed from links and navigation menus on the site. They can still be found using Google or other search engines. They were previously linked to on the main page’s side-bar menu that leads visitors to other “Notable Graves” pages, but have been removed.

- Also gone are any mention of six educational sections — which an Army spokesperson referred to as “modules” and the website calls “themes” — containing dozens of lesson plans, maps, biographies and other educational information created by Arlington, linking to dozens of documents. The lesson plans covered six topics, ranging from Women’s History to Medal of Honor recipients. The six modules have been removed from both a drop-down menu and from the site’s main Education page.

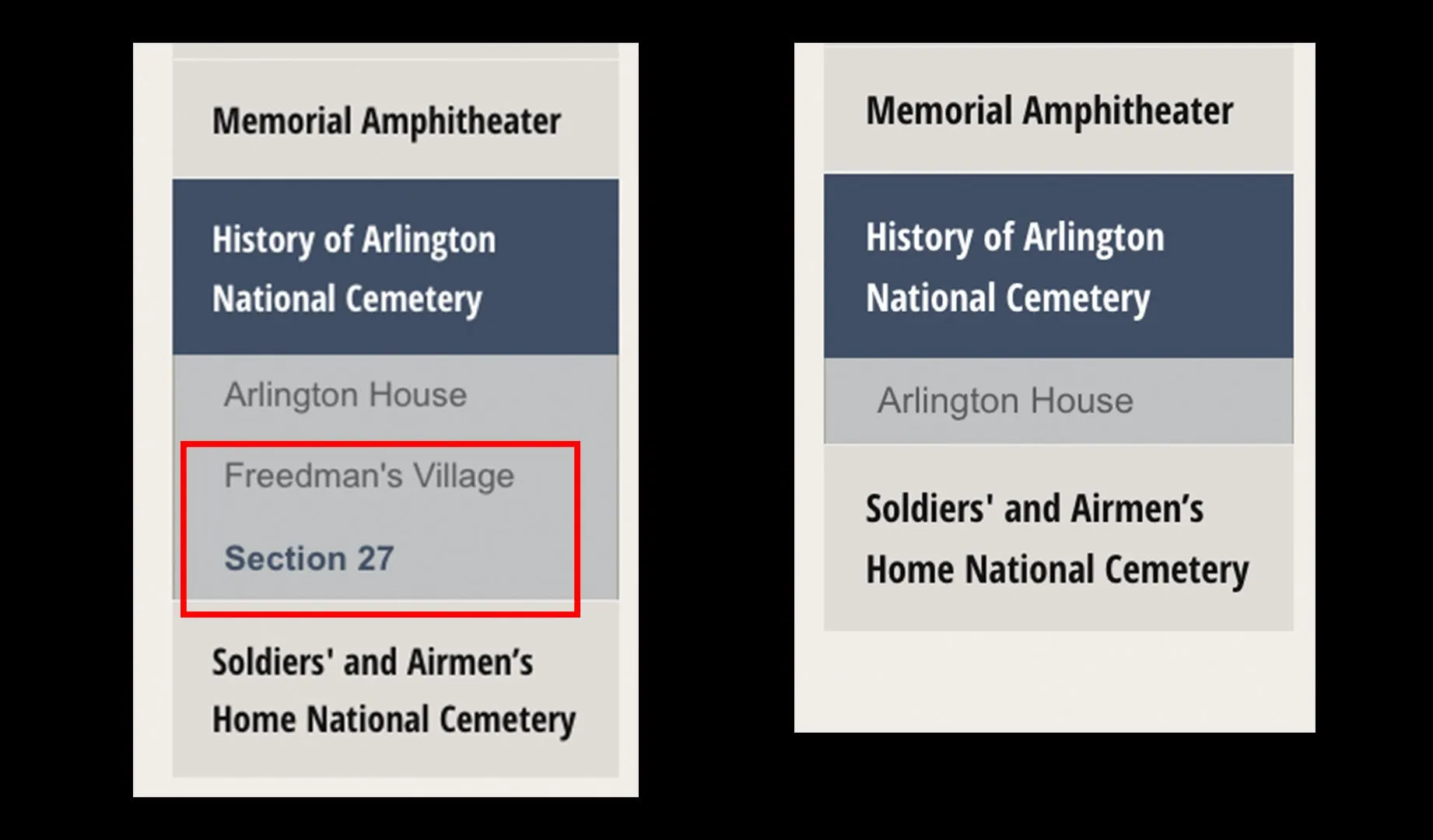

- Under the “History of Arlington National Cemetery” menus, pages on Freedman’s Village (archived version) and Section 27 (archived version) — two fundamental chapters in the cemetery’s post-Civil War history as a home for freed slaves — have been delinked. The pages were still accessible on March 12 among links embedded in the text on the main “History of Arlington” page.

- Some pages appear to have had phrases like “civil rights” and “racial justice” erased in favor of cliches referring to “service.”

Hidden ‘Notable Graves’ webpages

Some pages, while they do still exist on the Arlington National Cemetery website, cannot be navigated to from the website itself, and have essentially been walled off. Below are direct links to the pages as they exist at time of publication, as well as links to archived versions.

- African American History/(archived version): The hidden page of “Notable Graves” of Black service members includes 32 individuals and memorials to five groups, some of which include “co-mingled” remains of members of those groups. The individual graves on the list include dozens of Black veterans and other high-profile Black Americans with ties to the military or high government posts, including Gen. Colin Powell, boxing champion Joe Louis and Supreme Court Chief Justice Thurgood Marshall. The groups on the list include the Contraband militia of freed slaves, the Buffalo Soldiers of the Spanish American War, and the Tuskegee Airmen and 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion of World War II.

- Hispanic American History/(archived version): The unpublished list of “Notable Graves” for Hispanic service members includes nine individuals and a monument to the Borinqueneers, a unit of Puerto Rican soldiers in the Army’s 65th Infantry Regiment, who fought in the Korean War. Among the individual graves on the list is Pvt. Felix Longoria. Born and raised in Texas, Longoria enlisted in the Army in 1944. After he was killed in fighting in Luzon, Philippines on June 16, 1945, his remains were not recovered until 1948. In Texas, a funeral director refused to hold a wake for Longoria because of his Mexican roots. In response, then-Texas Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson authorized Longoria’s remains to be buried at Arlington in February 1949, with Johnson and his wife in attendance. His death and burial at Arlington became known as the “Felix Longoria Affair” and, according to historians, played a significant role in catalyzing Mexican-American political activism.

- Women’s History/(archived version): Among the listed “Notable Graves” of women buried at Arlington are Dr. Ollie Josephine Prescott Baird Bennett, a medical doctor who joined the Army in World War I, Maj. Gen. Marcelite Jordan Harris, the Air Force’s first African American female brigadier general, Lt. Kara Spears Hultgreen, the Navy’s first female carrier-based fighter pilot who flew F-14s, and Maj. Marie Therese Rossi, the first American woman to fly helicopters in combat, when she commanded a CH-47 Chinook helicopter company during Desert Storm (she died on a mission ferrying POWs on March 1, 1991, the day after a ceasefire agreement, which kept her from being awarded a posthumous Purple Heart).

Six educational modules have been removed from the website’s educational section (archived version here). The modules vary from walking tour maps and fact-sheets to classroom worksheets, PowerPoint presentations and lesson plans. A missing module on Nurses in the Spanish American War included six PowerPoint presentations tailored for elementary, middle school and high school classes.

Many bear only tangential relations to DEIA-related topics. An Arlington spokesperson confirmed the missing modules cover:

- “Civil War” (archived version) – 7 educational modules removed.

- “Environment at ANC” (archived version) – page renamed and 1 educational module removed.

- “Medal of Honor” (archived version) – 1 module removed with three walking tour guides.

- “Service Branches” (archived version) – 5 walking tour modules for notables graves of veterans of the Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps and Coast Guard.

- “Women’s History” (archived version) – 7 educational modules removed.

- “African-American History” (archived version) – 14 educational modules removed.

According to Archive.org pages, the Civil War section had 5 documents:

- A lesson plan designed for high school students that would “prompt analysis of different perspectives on the Civil War” using biographical sketches of those interred at Arlington.

- Maps and fact-sheets of a 5-mile self-guided walking tour covering “thousands of Civil War service members,” discussions of why the U.S. Army first occupied the property in 1861 and the “histories of enslavement and emancipation that this land also embodies.”

- A half-mile walking tour of Freedman’s Village, a “community of formerly enslaved African Americans, established in 1863” that lies on Arlington property and became the first largely black town in the Washington, D.C. area.

- Two modules on Section 27, where thousands of former slaves were buried in the years after the Civil War, often with “citizen” or “civilian” on their tombstone.

Though the lesson plans have been removed from the cemetery’s education page, a few of the documents can still be accessed indirectly. If a visitor navigates to the main “History of Arlington” page, links to the Freedman’s Village page are clickable in the text of the page. On that Freedman’s Village page, links to some of the still-live walking tours and other fact sheets are listed under “Additional Resources.” It’s unclear if these paths were left intentionally or overlooked in the unpublishing process.

‘Unpublished’ Medal of Honor material

But the missing lesson plans also cover topics with no obvious ties to the mandate to remove DEIA-related material, including three self-guided walking tours for the graves of Medal of Honor recipients. Each tour covers about 10 Medal of Honor recipients with directions to their graves and biographical fact-sheets.

Also missing are links to material Arlington dubbed “Honoring the Service Branches,” which until recently listed links to maps and fact-sheets for tours aimed at gravesites of specific notable members of the Marine Corps, Army, Navy, Air Force and Coast Guard. The page that previously held that material has been delinked and is blank.

None of the fact-sheets previously linked in the Medal of Honor or Service Branches pages mentioned the terms “diversity,” “equity,” or “inclusion,” according to archived copies reviewed by Task & Purpose.

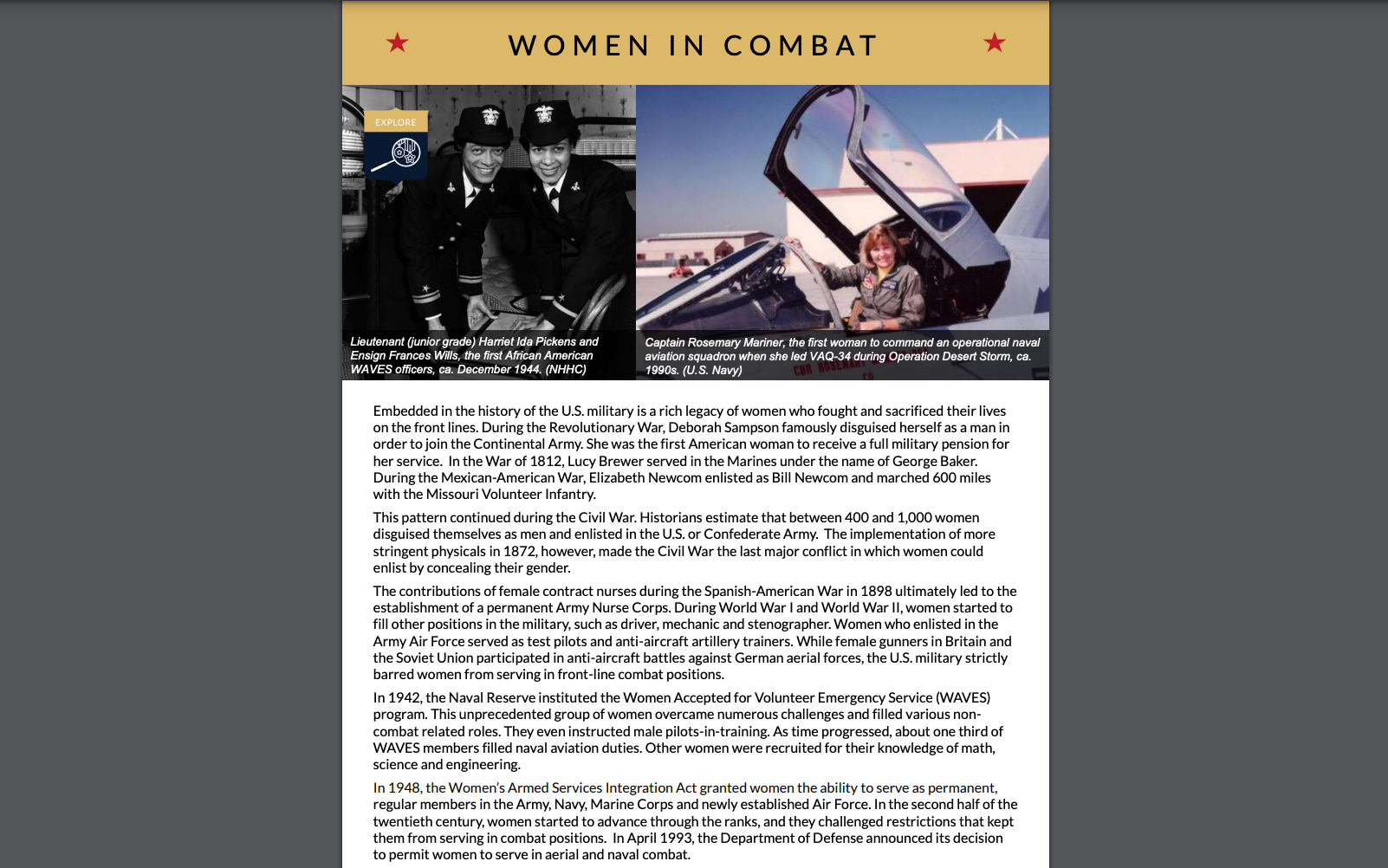

The Service Branches fact-sheets appear to contain a glancing reference to racial and gender disparities in military history. For example, the walking tour fact-sheet focused on notable Navy graves covers about a dozen, including Rear Adm. Richard Byrd, Fleet Adm. William “Bull” Halsey and a monument to the USS Maine. The pamphlet also includes three women, including Rear Adm. Grace Hopper, and one half-page essay entitled “Women in Combat” that reviews the history of women in naval service.

It may be a similar story for the material struck from the cemetery’s Medal of Honor educational page.

For example, the walking guide of the central part of the cemetery highlights four of the best-known graves in the cemetery: the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, 1st Lt. Audie Murphy, Gen. James “Jimmy” Doolittle and Marine Gunnery Sgt. John Basilone, along with Lt. Vernon Baker.

Baker, a World War II soldier, saw his Medal upgraded in later reviews, along with Sgt. Henry Johnson from World War II and Sgt. Cornelius Charlton, who fought in the Korean War. Johnson and Charlton are highlighted on two other walking tours that have been hidden from view on the website.

Baker was, according to his citation and the now-unpublished Arlington fact sheet, a one-man wrecking crew as a platoon commander during an assault on a German artillery post in Castle Aghinolfi, Italy in April 1945. Facing heavy fire, he shot his way past lines of defenders, survived a dud grenade landing next to him, and — moving forward alone — used his own grenades to blow open hatches to artillery bunkers. With 19 of his platoon’s 25 soldiers wounded or dead in the attack, he kept up his assault on machine gun nests to cover the platoon’s withdrawal.

In 1997, Baker’s Distinguished Service Cross for the fighting was upgraded to the Medal of Honor after the 1997 review, along with six other Black soldiers. Baker was the only of the seven still alive.

Vernon died in 2010, the walking tour fact-sheet says, and is interred at Arlington, Section 59, Grave 4408.