Yes…and it’s always the same people who fall for it.You're right. There is no evidence of sext tests or hormone testing done my the IBA. They just made that shit up because she beat the favorite of their Oligarch president and the Gazprom funders.

It's amazing how easily people fall for the most transparent Russian propaganda.

Two Biological Males Allowed to Fight in Female Div. At Paris Olympics

- Thread starter TomFord1980

- Start date

People don't realize that in the real world, testosterone levels in women are a spectrum, just like how some men have more estrogen than others.The Olympic committee do and no rules set against natural high level testosterone. Game on.

LOL they're putting up the X not to stand with women but rather to show their signature Wakanda Forever, they did the same previously at other Olympic Games. https://x.com/Kearns_Richard_/status/1822097456806474137?t=usdx5m8WzFX22OpmM_O3gQ&s=19

''A normal testosterone level for you will depend on your gender and age. Normal total testosterone results in adult men: Ages 19 to 49 -- 249 - 836 nanograms per deciliter (ng/dL) Ages 50 and older -- 193 - 740 ng/dL.''People don't realize that in the real world, testosterone levels in women are a spectrum, just like how some men have more estrogen than others.

''Normal total testosterone results in adult women: Ages 19 to 49 -- 8 - 48 ng/dL. Ages 50 and older -- 2 - 41 ng/dL''

The IOC never tested their female boxers for hormones or sex....They relied on passport which is self reported.

That's funny because if a *man* has elevated testosterone he's immediately banned until further investigation.People don't realize that in the real world, testosterone levels in women are a spectrum, just like how some men have more estrogen than others.

*Due to nonsensical modern day politics, the definition of "man" may vary.

Immense harm done from a cheek swab?

And to make this fair, I think all Olympic athletes should to this test.

It's not about targeting 1 or 2 individuals.

It's not about targeting 1 or 2 individuals.

I haven't read this thread so can anyone let me know if this was a true cockfight or just more arguing?

While I agree biological males have no place in women's sports... you rughties sure are obsessed over cock.Yes, it was a cockfight alright........no pun intended.......LMAO

"While I agree biological males have no place in women's sports... The agenda tells me to shut my mouth and fall in line."

You'd think they'd be all over pole vault instead.While I agree biological males have no place in women's sports... you rughties sure are obsessed over cock.

You poor thing..."While I agree biological males have no place in women's sports... The agenda tells me to shut my mouth and fall in line."

Who is "the agenda"?

Anyone stopping you posting here?

You are free to express your opinions but tbh, most people really don't give as much of a fuck about the opinions of others.

Well that video is going to keep @mitchell76 busy 'doing his own research' for a few hours...You'd think they'd be all over pole vault instead.

You'd think they'd be all over pole vault instead.

A boy goes to the Olympics and and approaches a man with a long stick, and says to him, "Are you a pole vaulter?"

"No, I'm German," says the man, "but how did you know my name?"

While I agree biological males have no place in women's sports... you rughties sure are obsessed over cock.

Not just righties...

Lia Thomas and the long tradition of 'gender policing' female athletes

For as long as women have excelled at sports in the modern era, their gender and sexuality have faced fierce scrutiny, historians say.

By Julie Compton

March 16, 2022, 3:10 PM EDT

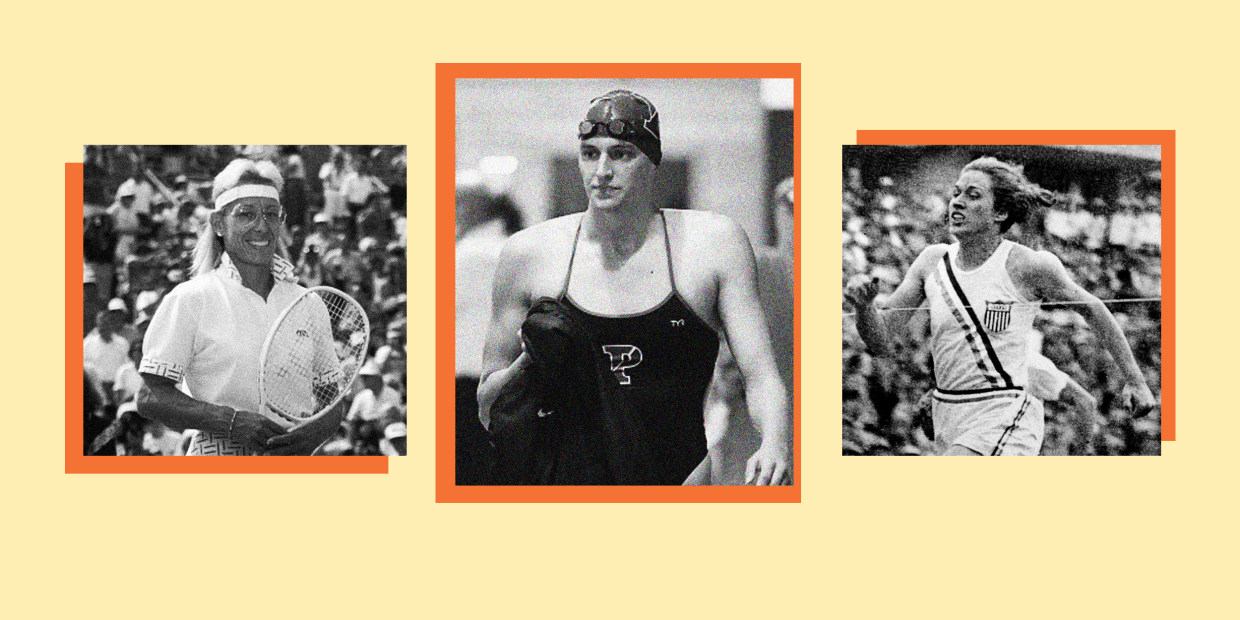

In a February 1937 issue of Look magazine, a photo of American Olympic runner Helen Stephens appeared below the caption “What Do You Think? Is This a Man Or a Woman?” The image and the accompanying query were part of a larger feature titled: “When Is a Woman Actually a Woman? Today’s Chief Worry Among Athletic Officials.”

In the aftermath, Stephens — a two-time Olympic champion who never lost a race — lost valuable career and scholarship opportunities, said Sharon Kinney-Hanson, the author of “The Life of Helen Stephens: The Fulton Flash.”

“You think about what feminine standards were in her era: It was the glamor, you had to be gorgeous, you had to be big-chested and curvaceous, and Helen was not interested in that,” Kinney-Hanson said. “She was interested in sports, making a career of it.”

Helen Stephens at Brown University Field in Providence, R.I., on July 4, 1936.Bettmann Archive / Getty Images

Helen Stephens at Brown University Field in Providence, R.I., on July 4, 1936.Bettmann Archive / Getty Images

While much has changed for female athletes since Stephens’ day, suspicion surrounding their gender and sexuality — from offensive remarks to sex verification tests — remains. Several historians argue that the heated debate surrounding transgender college swimmer Lia Thomas, whose record-breaking season has thrust her unwillingly into the national spotlight, is a continuation of that century-old legacy.

“Historically, there’s just been a concern that sports would masculinize women or that women might either feminize sports or that you would lose gender distinctions that many people valued,” said Susan Cahn, a history professor at the University of Buffalo and the author of “Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Women’s Sport.”

She added that trans and intersex athletes — those who are born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not fit the typical “male” or “female” categories — further blur boundaries and raise questions about how separate and distinct sex and gender really are.

“The dislike of women who appear masculine or seem to compete in ways that are masculine extends to transgender women and intersex people competing as women,” Cahn said.

Sex verification tests

By the 1940s, sporting authorities began conducting ad hoc sex testing on female athletes whose gender was deemed suspicious, according to Human Rights Watch, which said it typically consisted of physical and visual exams by doctors.

During the Cold War era of the 1960s, Soviet track and field stars Irina and Tamara Press together set at least 22 world records, a feat that triggered slews of “negative commentary” from the media, in which the sisters were “constantly compared to male athletes,” said Lindsay Parks Pieper, an associate professor of sport management at the University of Lynchburg in Virginia and the author of “Sex Testing: Gender Policing in Women’s Sports.”

Amid fears that Eastern European teams could be harboring male impostors, sports governing bodies, including the International Association of Athletics Federations (now World Athletics) and the International Olympic Committee started to require chromosomal testing of all female athletes to ensure fair competition, a controversial practice that was eventually banned by the late ’90s.

“They found that it was essentially impossible to use one single cross qualifier to determine an athlete’s sex,” Pieper said, referring to a range of genetic tests used by sporting authorities.

However, sporting authorities still reserve the right to test female athletes suspected of having physical advantages, over concerns that they either could be doping or might be intersex.

By the 2010s, sporting authorities had begun zeroing in on athletes’ testosterone levels, with much of their suspicion falling on high-performing athletes of color from the Global South, Pieper said. South African middle distance runner Caster Semenya and Indian sprinter Dutee Chand, for example, were required to undergo tests over concerns they were too fast.

Caster Semenya competes in the women's 1500-meter final at the 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games on April 10, 2018.Saeed Khan / AFP via Getty Images

Semenya, in particular, came under a media storm over her muscular build. After Semenya won the 800 meters at the world track and field championships in Berlin in 2009, a Time magazine storyreminiscent of Look’s 1937 spread on Helen Stephens featured Semenya’s photo and asked, “Could This Women’s World Champ Be a Man?”

After she was barred from competing in 400-meter-to-1-mile races unless she medically reduced her testosterone, Semenya, who is legally female, took her case to the international Court of Arbitration for Sport in 2019, claiming discrimination. According to court documents reported on by TheAssociated Press, World Athletics argued that Semenya is “biologically male,” a claim that she said “hurts more than I can put in words.”

After she lost her case, Semenya was unable to compete in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and is now challenging the ruling in the European Court of Human Rights.

“This fight is not just about me, it’s about taking a stand and fighting for dignity, equality and the human rights of women in sport,” Semenya wrote on Twitter in February 2021. “All we ask is to be able to run free as the strong and fearless women we are!!”

Although normal testosterone levels can vary widely among men (around 300 to 1,000 nanograms per deciliter), only female athletes are subjected to such tests. Pieper said sports in the U.S. have traditionally served as a space for men to cultivate and prove masculinity and that high-performing male athletes have never been viewed as suspicious, regardless of their performances.

“If a woman is good at sports,” she said, people feel a need “to question why that is.”

'Homophobia as a weapon'

Scrutiny surrounding the gender of female athletes has often gone hand in hand with questions about their sexuality.

Mildred “Babe” Didrikson Zaharias, a multisport athlete who won two gold medals in the 1932 Summer Olympics, was subjected to both, Pieper said. Sports journalists, she said, frequently derided Didrikson as a “muscle moll,” a term used to describe women who were considered “sexually deviant” or lesbians.

“Those were accusations lobbed at her as a way, I would argue, to downplay her athleticism or take away from her athleticism, and then you see that continued throughout history,” Pieper said.

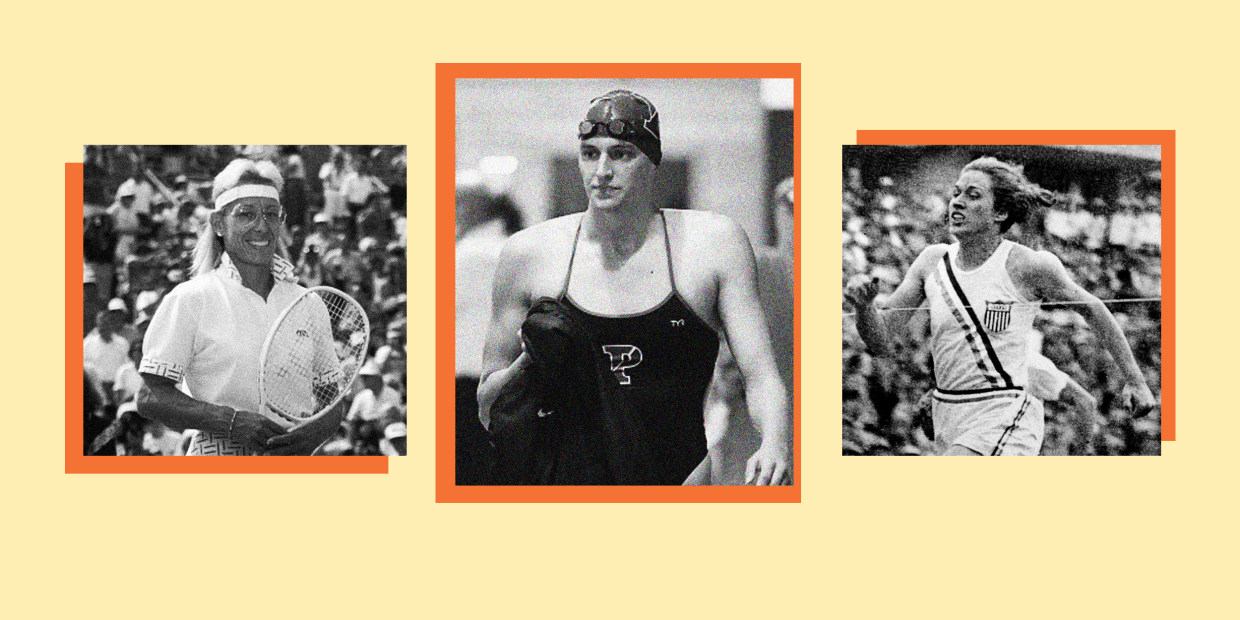

By the 1980s, sports journalists had begun fixating on tennis star Martina Navratilova’s muscular physique, often describing her as “bionic,” with some even claiming she should be competing in the men’s tournaments, Cahn said.

Martina Navratilova plays Chris Evert in the Women's Singles Final at the French Open Tennis Championship in Paris on June 9, 1984.Steve Powell / Getty Images

After the media outed Navratilova and fellow tennis legend Billie Jean King as gay, a fear of lesbianism began to grip the world of women’s sports. King and Navratilova lost valuable sponsorship opportunities and faced the potential ends of their careers.

Even before they were outed, sporting officials had long tried to squash the stereotype that female athletes were lesbians by, among other things, requiring that they wear ladylike uniforms, according to historians. Aside from fighting stereotypes that they simply could not be good athletes, Cahn said, female athletes were also under “real pressure to prove femininity.”

“I think the fear was that women would claim space in women’s sports and would try to compete and would someday compete as equals or near equals” to men, she said. “And so, homophobia was a weapon just to dismiss women and to denigrate women athletes.”

Worries about lesbianism went beyond athletes, Pieper said.

“Coaches, largely in the ’80s, would accuse other coaches of being lesbian as a negative characteristic to kind of scare athletes to come to their schools, to come onto their team,” she said.

Blurring the 'boundaries of gender'

The first transgender female athlete to be thrown into the national spotlight was Renée Richards, who is believed to be the first trans woman to play a professional sport.

Richards sued the U.S. Tennis Association in 1977 over a requirement that women must undergo genetic testing to compete in the U.S. Open. She won the case but lost a number of matches that year, including matches against Navratilova and Britain’s Virginia Wade.

Nevertheless, Richards ignited fears that trans women would “herald the end of women’s sports as we know it,” said Joanna Harper, a medical physicist and the author of “Sporting Gender: The History, Science, and Stories of Transgender and Intersex Athletes.”

“Renée was the pioneer trans woman. She was the first one,” Harper said. “That will always be the most important thing that she has done.”

Decades after Richards became the first, only a handful of trans athletes have managed to break sports barriers. In 2019, track star CeCé Telfer became the first openly trans person to win an NCAA title. And last year, New Zealand weightlifter Laurel Hubbard became the first out trans woman to compete in the Olympics, where she did not win any medals. Fewer than 30 trans athletes have competed openly in the NCAA, according to the LGBTQ sports publication Out Sports, and few have made headlines.

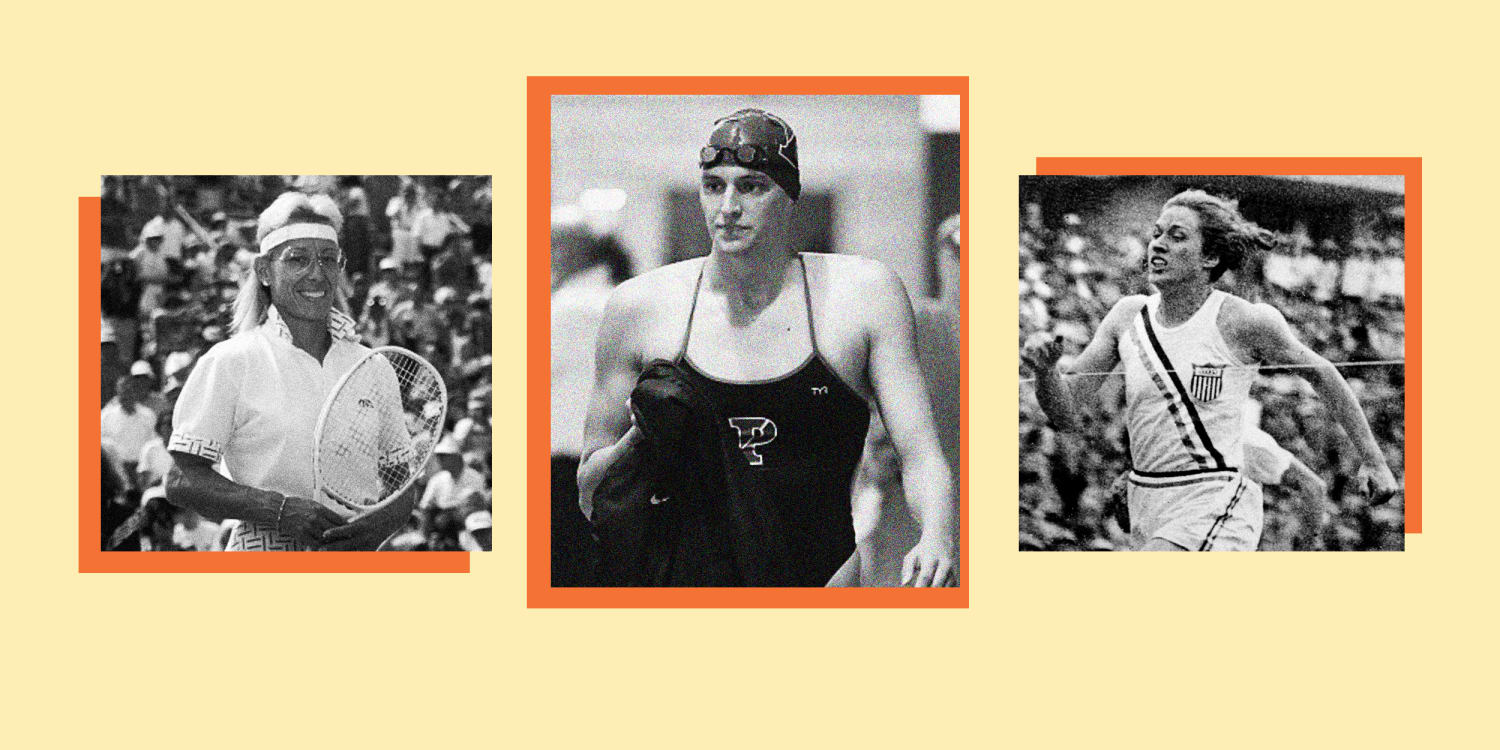

Among the few is trans swimmer Lia Thomas of the University of Pennsylvania, who broke records at the Ivy League Championships last month and is scheduled to compete in the NCAA Women’s Division I Swimming and Diving Championships, which begin Wednesday in Atlanta. Thomas hasattracted intense media scrutiny over her appearance, with conservative news sites, in particular, referring to her as a man, using her former name (also known as “deadnaming”) and featuring photos of her from before her transition.

Though headlines frequently portray her as unbeatable, Thomas has had her share of losses, including at a January meet against Yale University and Dartmouth College where she came in sixth in the 100-yard freestyle, losing to four cisgender women and Yale's Iszac Henig, a transgender man who has not yet started testosterone.

“I’m a woman, just like anybody else on the team,” Thomas, 22, told Sports Illustrated this month in response to the criticism. “I’ve always viewed myself as just a swimmer. It’s what I’ve done for so long; it’s what I love.”

In what was seen largely as a victory for trans athletes, the International Olympic Committee announced a newframework in November that scrapped requirements for “medically unnecessary” procedures and treatment that placed limits on testosterone levels, although it left requirements up to individual sports governing bodies. Last month, amid growing negative media commentary about Thomas, USA Swimming, the sport’s national governing body, switched its policy to require elite trans female athletes to suppress their testosterone for three years, up from the previous one year, a change many of Thomas’ supporters suspected was an attempt to prevent her from competing in the NCAA Championships. The NCAA has not adopted the change, meaning Thomas, who began transitioning in May 2019, will be allowed to compete.

Harper said testosterone-based policies for trans athletes in general do not amount to gender policing. However, she called USA Swimming’s new 36-month policy “problematic,” because a trans woman’s hemoglobin — blood proteins responsible for carrying oxygen to the muscles — drop to similar levels as in cisgender women in under a year of hormone therapy, causing them to lose a significant amount of endurance.

While the science is limited, recent studies have found that trans women tend, on average, to maintain an athletic edge even after a year of hormone therapy, despite losing much of their muscle mass. The subjects of these studies were not elite or professional athletes, but the findings do throw into question how much time, following hormone therapy, trans athletes should have to wait before they compete.

“The question isn’t ‘Do trans women have advantages?’ Because yes, that is so obviously true,” Harper said, adding that it iss normal for athletes to have certain advantages and that any advantages trans women have are not necessarily unfair. “But can trans women and cis women compete against one another in meaningful competition? That’s the important question. That’s the interesting question. And that’s a question that we don’t have a 100 percent firm answer yet.”

'How can you compete if you’re not allowed to win?'

Despite decades of scrutiny, female athletes have seen the world of professional sports change dramatically since Helen Stephens’ infamous Look magazine photo.

For example, this year’s U.S. Olympic team had the most female athletes in the history of the Winter Games, and an increasing number of openly LGBTQ Olympians have participated in the Olympics, with queer women typically far outnumbering their male counterparts. And just last month, the U.S. Women’s National Team won a major legal battle against the U.S. Soccer Federation, reaching a landmark agreement that will ensure equal pay for male and female soccer players.

Despite gains, female athletes still face obstacles, especially when it comes to financing, equal pay and media coverage. And some trans advocates say the focus on this small subset of athletes — which has culminated in 11 states’ passing bills to ban trans women and girls from female sports teams in just the past two years — overshadows those other issues.

Cahn said that while there are legitimate questions to be asked when it comes to trans female athletes and competitive fairness, conservatives are focusing on transgender athletes to “draw the line and defend traditional notions of gender.”

“They’re doing it in the name of fairness for girls, and it’s people who’ve never fought for gender equity or equality or to increase the budget for women’s sports,” she said.

Meanwhile, outrage and speculation over Thomas continue to garner headlines, with many of her critics expecting her to smash records in the NCAA finals this week. Harper said to expect “a huge outcry” if she wins any of her events.

“It’s a truism of trans athletes that we can compete in women’s sports as long as we don’t win,” said Harper, who is trans. “If we win, then it’s problematic. And, of course, how can you compete if you’re not allowed to win?”

www.nbcnews.com

www.nbcnews.com

For as long as women have excelled at sports in the modern era, their gender and sexuality have faced fierce scrutiny, historians say.

By Julie Compton

March 16, 2022, 3:10 PM EDT

In a February 1937 issue of Look magazine, a photo of American Olympic runner Helen Stephens appeared below the caption “What Do You Think? Is This a Man Or a Woman?” The image and the accompanying query were part of a larger feature titled: “When Is a Woman Actually a Woman? Today’s Chief Worry Among Athletic Officials.”

In the aftermath, Stephens — a two-time Olympic champion who never lost a race — lost valuable career and scholarship opportunities, said Sharon Kinney-Hanson, the author of “The Life of Helen Stephens: The Fulton Flash.”

“You think about what feminine standards were in her era: It was the glamor, you had to be gorgeous, you had to be big-chested and curvaceous, and Helen was not interested in that,” Kinney-Hanson said. “She was interested in sports, making a career of it.”

While much has changed for female athletes since Stephens’ day, suspicion surrounding their gender and sexuality — from offensive remarks to sex verification tests — remains. Several historians argue that the heated debate surrounding transgender college swimmer Lia Thomas, whose record-breaking season has thrust her unwillingly into the national spotlight, is a continuation of that century-old legacy.

“Historically, there’s just been a concern that sports would masculinize women or that women might either feminize sports or that you would lose gender distinctions that many people valued,” said Susan Cahn, a history professor at the University of Buffalo and the author of “Coming on Strong: Gender and Sexuality in Women’s Sport.”

She added that trans and intersex athletes — those who are born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not fit the typical “male” or “female” categories — further blur boundaries and raise questions about how separate and distinct sex and gender really are.

“The dislike of women who appear masculine or seem to compete in ways that are masculine extends to transgender women and intersex people competing as women,” Cahn said.

Sex verification tests

By the 1940s, sporting authorities began conducting ad hoc sex testing on female athletes whose gender was deemed suspicious, according to Human Rights Watch, which said it typically consisted of physical and visual exams by doctors.

During the Cold War era of the 1960s, Soviet track and field stars Irina and Tamara Press together set at least 22 world records, a feat that triggered slews of “negative commentary” from the media, in which the sisters were “constantly compared to male athletes,” said Lindsay Parks Pieper, an associate professor of sport management at the University of Lynchburg in Virginia and the author of “Sex Testing: Gender Policing in Women’s Sports.”

Amid fears that Eastern European teams could be harboring male impostors, sports governing bodies, including the International Association of Athletics Federations (now World Athletics) and the International Olympic Committee started to require chromosomal testing of all female athletes to ensure fair competition, a controversial practice that was eventually banned by the late ’90s.

“They found that it was essentially impossible to use one single cross qualifier to determine an athlete’s sex,” Pieper said, referring to a range of genetic tests used by sporting authorities.

However, sporting authorities still reserve the right to test female athletes suspected of having physical advantages, over concerns that they either could be doping or might be intersex.

By the 2010s, sporting authorities had begun zeroing in on athletes’ testosterone levels, with much of their suspicion falling on high-performing athletes of color from the Global South, Pieper said. South African middle distance runner Caster Semenya and Indian sprinter Dutee Chand, for example, were required to undergo tests over concerns they were too fast.

Caster Semenya competes in the women's 1500-meter final at the 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games on April 10, 2018.Saeed Khan / AFP via Getty Images

Semenya, in particular, came under a media storm over her muscular build. After Semenya won the 800 meters at the world track and field championships in Berlin in 2009, a Time magazine storyreminiscent of Look’s 1937 spread on Helen Stephens featured Semenya’s photo and asked, “Could This Women’s World Champ Be a Man?”

After she was barred from competing in 400-meter-to-1-mile races unless she medically reduced her testosterone, Semenya, who is legally female, took her case to the international Court of Arbitration for Sport in 2019, claiming discrimination. According to court documents reported on by TheAssociated Press, World Athletics argued that Semenya is “biologically male,” a claim that she said “hurts more than I can put in words.”

After she lost her case, Semenya was unable to compete in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and is now challenging the ruling in the European Court of Human Rights.

“This fight is not just about me, it’s about taking a stand and fighting for dignity, equality and the human rights of women in sport,” Semenya wrote on Twitter in February 2021. “All we ask is to be able to run free as the strong and fearless women we are!!”

Although normal testosterone levels can vary widely among men (around 300 to 1,000 nanograms per deciliter), only female athletes are subjected to such tests. Pieper said sports in the U.S. have traditionally served as a space for men to cultivate and prove masculinity and that high-performing male athletes have never been viewed as suspicious, regardless of their performances.

“If a woman is good at sports,” she said, people feel a need “to question why that is.”

'Homophobia as a weapon'

Scrutiny surrounding the gender of female athletes has often gone hand in hand with questions about their sexuality.

Mildred “Babe” Didrikson Zaharias, a multisport athlete who won two gold medals in the 1932 Summer Olympics, was subjected to both, Pieper said. Sports journalists, she said, frequently derided Didrikson as a “muscle moll,” a term used to describe women who were considered “sexually deviant” or lesbians.

“Those were accusations lobbed at her as a way, I would argue, to downplay her athleticism or take away from her athleticism, and then you see that continued throughout history,” Pieper said.

By the 1980s, sports journalists had begun fixating on tennis star Martina Navratilova’s muscular physique, often describing her as “bionic,” with some even claiming she should be competing in the men’s tournaments, Cahn said.

Martina Navratilova plays Chris Evert in the Women's Singles Final at the French Open Tennis Championship in Paris on June 9, 1984.Steve Powell / Getty Images

After the media outed Navratilova and fellow tennis legend Billie Jean King as gay, a fear of lesbianism began to grip the world of women’s sports. King and Navratilova lost valuable sponsorship opportunities and faced the potential ends of their careers.

Even before they were outed, sporting officials had long tried to squash the stereotype that female athletes were lesbians by, among other things, requiring that they wear ladylike uniforms, according to historians. Aside from fighting stereotypes that they simply could not be good athletes, Cahn said, female athletes were also under “real pressure to prove femininity.”

“I think the fear was that women would claim space in women’s sports and would try to compete and would someday compete as equals or near equals” to men, she said. “And so, homophobia was a weapon just to dismiss women and to denigrate women athletes.”

Worries about lesbianism went beyond athletes, Pieper said.

“Coaches, largely in the ’80s, would accuse other coaches of being lesbian as a negative characteristic to kind of scare athletes to come to their schools, to come onto their team,” she said.

Blurring the 'boundaries of gender'

The first transgender female athlete to be thrown into the national spotlight was Renée Richards, who is believed to be the first trans woman to play a professional sport.

Richards sued the U.S. Tennis Association in 1977 over a requirement that women must undergo genetic testing to compete in the U.S. Open. She won the case but lost a number of matches that year, including matches against Navratilova and Britain’s Virginia Wade.

Nevertheless, Richards ignited fears that trans women would “herald the end of women’s sports as we know it,” said Joanna Harper, a medical physicist and the author of “Sporting Gender: The History, Science, and Stories of Transgender and Intersex Athletes.”

“Renée was the pioneer trans woman. She was the first one,” Harper said. “That will always be the most important thing that she has done.”

Decades after Richards became the first, only a handful of trans athletes have managed to break sports barriers. In 2019, track star CeCé Telfer became the first openly trans person to win an NCAA title. And last year, New Zealand weightlifter Laurel Hubbard became the first out trans woman to compete in the Olympics, where she did not win any medals. Fewer than 30 trans athletes have competed openly in the NCAA, according to the LGBTQ sports publication Out Sports, and few have made headlines.

Among the few is trans swimmer Lia Thomas of the University of Pennsylvania, who broke records at the Ivy League Championships last month and is scheduled to compete in the NCAA Women’s Division I Swimming and Diving Championships, which begin Wednesday in Atlanta. Thomas hasattracted intense media scrutiny over her appearance, with conservative news sites, in particular, referring to her as a man, using her former name (also known as “deadnaming”) and featuring photos of her from before her transition.

Though headlines frequently portray her as unbeatable, Thomas has had her share of losses, including at a January meet against Yale University and Dartmouth College where she came in sixth in the 100-yard freestyle, losing to four cisgender women and Yale's Iszac Henig, a transgender man who has not yet started testosterone.

“I’m a woman, just like anybody else on the team,” Thomas, 22, told Sports Illustrated this month in response to the criticism. “I’ve always viewed myself as just a swimmer. It’s what I’ve done for so long; it’s what I love.”

In what was seen largely as a victory for trans athletes, the International Olympic Committee announced a newframework in November that scrapped requirements for “medically unnecessary” procedures and treatment that placed limits on testosterone levels, although it left requirements up to individual sports governing bodies. Last month, amid growing negative media commentary about Thomas, USA Swimming, the sport’s national governing body, switched its policy to require elite trans female athletes to suppress their testosterone for three years, up from the previous one year, a change many of Thomas’ supporters suspected was an attempt to prevent her from competing in the NCAA Championships. The NCAA has not adopted the change, meaning Thomas, who began transitioning in May 2019, will be allowed to compete.

Harper said testosterone-based policies for trans athletes in general do not amount to gender policing. However, she called USA Swimming’s new 36-month policy “problematic,” because a trans woman’s hemoglobin — blood proteins responsible for carrying oxygen to the muscles — drop to similar levels as in cisgender women in under a year of hormone therapy, causing them to lose a significant amount of endurance.

While the science is limited, recent studies have found that trans women tend, on average, to maintain an athletic edge even after a year of hormone therapy, despite losing much of their muscle mass. The subjects of these studies were not elite or professional athletes, but the findings do throw into question how much time, following hormone therapy, trans athletes should have to wait before they compete.

“The question isn’t ‘Do trans women have advantages?’ Because yes, that is so obviously true,” Harper said, adding that it iss normal for athletes to have certain advantages and that any advantages trans women have are not necessarily unfair. “But can trans women and cis women compete against one another in meaningful competition? That’s the important question. That’s the interesting question. And that’s a question that we don’t have a 100 percent firm answer yet.”

'How can you compete if you’re not allowed to win?'

Despite decades of scrutiny, female athletes have seen the world of professional sports change dramatically since Helen Stephens’ infamous Look magazine photo.

For example, this year’s U.S. Olympic team had the most female athletes in the history of the Winter Games, and an increasing number of openly LGBTQ Olympians have participated in the Olympics, with queer women typically far outnumbering their male counterparts. And just last month, the U.S. Women’s National Team won a major legal battle against the U.S. Soccer Federation, reaching a landmark agreement that will ensure equal pay for male and female soccer players.

Despite gains, female athletes still face obstacles, especially when it comes to financing, equal pay and media coverage. And some trans advocates say the focus on this small subset of athletes — which has culminated in 11 states’ passing bills to ban trans women and girls from female sports teams in just the past two years — overshadows those other issues.

Cahn said that while there are legitimate questions to be asked when it comes to trans female athletes and competitive fairness, conservatives are focusing on transgender athletes to “draw the line and defend traditional notions of gender.”

“They’re doing it in the name of fairness for girls, and it’s people who’ve never fought for gender equity or equality or to increase the budget for women’s sports,” she said.

Meanwhile, outrage and speculation over Thomas continue to garner headlines, with many of her critics expecting her to smash records in the NCAA finals this week. Harper said to expect “a huge outcry” if she wins any of her events.

“It’s a truism of trans athletes that we can compete in women’s sports as long as we don’t win,” said Harper, who is trans. “If we win, then it’s problematic. And, of course, how can you compete if you’re not allowed to win?”

Lia Thomas and the long tradition of 'gender policing' female athletes

For as long as women have excelled at sports in the modern era, their gender and sexuality have faced fierce scrutiny, historians say.

Last edited:

Imane (and Lin Yu-Ting) is indeed the genotype male (xy chromosome). At birth in many countries including Canada we use the phenotype to assign the sex at birth. Phenotype are observations on the outwards features and characteristic of the person. Imane at birth was incorrectly assigned the sex female based on what doctors (no fault of their own if they are not required to perform chromosome testing) perceived to be a vagina. In fact it was actually a very-undervirilized penis due to the condition known as 5-alpha reductase deficiency (5ARD). Those with the condition 5ARD have male anatomy. They have testicles. And those testicles produce testosterone. This testestone during puberty separates male development from female development. But as well after puberty males walk around with signicantly more testestone than females. Otherwise those with 5ARD do not have any female anatomy (uterus, ovaries, etc).Crazy how people pinned her as male and just ran with the story without doing any due diligence.

This is why in sports we have the Male and Female category. However seeing we use the language "Men" and "Woman" category, we have allowed gender ideology politics to ruin the integrity of sports.

You are in denial that there is a IOC coverup. So far the IOC has used their powers to discredit the IBA. All the experts in the field of Science are speaking up.

Testing sex and gender in sports; reinventing, reimagining and reconstructing histories

As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health.

Learn more: |

2010 Dec; 34(4): 157–163.

Abstract

Most international sports organisations work on the premise that human beings come in one of two genders: male or female. Consequently, all athletes, including intersex and transgender individuals, must be assigned to compete in one or other category. Since the 1930s (not, as is popularly suggested, the 1960s) these organisations have relied on scientific and medical professionals to provide an ‘objective’ judgement of an athlete's eligibility to compete in women's national and international sporting events. The changing nature of these judgements reflects a great deal about our cultural, social and national prejudices, while the matter of testing itself has become a site of conflict for feminists and human rights activists. Because of the sensitive nature of this subject, histories of sex testing are difficult to write and research; this has lead to the repetition of inaccurate information and false assertions about gender fraud, particularly in relation to the ‘classic’ cases of Stella Walsh and Heinrich/Hermann/Dora Ratjen. As historians, we need to be extremely careful to differentiate between mythologies and histories.

The athletic girl not unfeminine1

The relationship between femininity and physical exercise is well studied by historians; in fact, it is probably better analysed and certainly more problematised than the relationship between masculinity and sport.2 It comes as no surprise that as major international sporting events were developed in the very late nineteenth century issues of physical display, modesty, muscularity, competition and the perpetual risk of sterility were all used to exclude women from many sporting activities.

Virtually the only way women could participate in competitive sport was through sexually segregated events.

The standard account of this process is as follows: the early years of the twentieth century are generally represented as a period of struggle and triumph for women's sports, with the eventual acceptance of a significant women's programme in the Olympics in 1924 and the proliferation of national organisations for women's sport.3

But as international sport took its place as ‘sublimated war’ at mid-century, the desire to win apparently became so pressing for some nations that deliberate and systematic cheating took place in both the men's and women's events. Consequently, doping and gender fraud became central concerns in the late 1950s and 60s, resulting in the eventual introduction of systematic testing for both at international sporting events in the late 1960s. The usual explanation given for the introduction of sex testing is a list of gender frauds (or suspected frauds) most of whom fulfil a specific stereotype: physically muscular, deep-voiced competitors living under totalitarian, fascist or communist regimes.

Amongst the ‘canon’ of gender frauds are normally the well-built and extremely successful Ukrainian sisters, Irina and Tamara Press, who dropped out of international competition when gender tests were introduced.4 For an earlier example, the usual name listed is Hermann Ratjen, who, we are told, through loyalty to the Hitler Youth, bound his genitals and competed as a woman – Dora Ratjen – at the 1936 Berlin Games. Ratjen may have been discovered as a fraud at a sporting event in the late 1930s, and was definitively revealed by a journalist in the 1950s, to whom he told his story.5Ratjen's case has even been made into a feature-length, award-winning movie.

There are three problems with this account. Firstly, it ignores the fact that systematic sex testing, of a sort, existed at least as early as the 1940s. Secondly it obscures the fact that the first well-known gender ‘frauds’ in international sport were not Nazi sympathisers, or Communist state athletes, but a British shot putter, and a Czechoslovakian runner. Finally, Hermann Ratjen's name was not Hermann, but Heinrich, and documents (including medical records) released after his death in 2008 suggest that rather than being a conspiracy, his place on the 1936 German women's high-jump team is explained by a more mundane and human case of gender uncertainty, medical error, fear and embarrassment.

The story of sex testing, and histories of sex testing, in international sport tell us a great deal about social attitudes to gender, and how the co-option of science in sport (however it is resisted by scientists and human rights campaigners) can act to essentialize social categories.6 Sex testing, after all, is a tautological (or at least circular) process: the activities which we recognise as sports are overwhelmingly those which favour a physiology which we consider ‘masculine’. As a general rule, the competitor who is taller, has a higher muscle-to-fat ratio, and the larger heart and lungs (plus some other cardio-respiratory factors) will have the sporting advantage. It is therefore inevitable that any woman who is good at sport will tend to demonstrate a more ‘masculine’ physique than women who are not good at sport. What the sex test effectively does, therefore, is provide an upper limit for women's sporting performance; there is a point at which your masculine-style body is declared ‘too masculine’, and you are disqualified, regardless of your personal gender identity.

For men there is no equivalent upper physiological limit – no kind of genetic, or hormonal, or physiological advantage is tested for, even if these would give a ‘super masculine’ athlete a distinct advantage over the merely very athletic ‘normal’ male. (Of course, both men and women are liable to the same testing regimes when it comes to external sources of advantage, i.e. doping.) There are probably hundreds of genetic variations which lead to ‘unfair’ advantages in sport; only those associated with gender are used to exclude or disqualify athletes.

This article will explore how this unequal situation came about, and discuss in brief the various technologies of gender and sex testing in sports. ‘Gender’, ‘sex’ and ‘femininity’ are often used interchangeably when referring to testing in sports despite having quite different meanings; in this article I will quote directly from the primary sources or use the phrase ‘sex testing’.7 More importantly I will also attempt to disrupt the comfortable narratives we have in place of sex-frauds being over-competitive athletes from non-democratic regimes.8

The canon of gender frauds

There is a straightforward narrative path through the history of gender testing, which takes as its earliest starting point the Berlin Olympics of 1936. This is where Ratjen competed as a woman in the high-jump, but our attention is more often directed at the 100 m race. Here the American runner Helen Stephens (the ‘Fulton Flash’) was accused of being a man when she narrowly beat the favourite, Polish runner Stanisława Walasiewicz. Stephens underwent an unspecified test and was declared a woman by the Berlin authorities, taking gold.9 Nearly four and a half decades later, in 1980, Walasiewicz (now known by her Anglicized name, Stella Walsh, which will be used through the rest of this article) was shot dead in a department store car park in Ohio. She had emigrated to the USA in 1947, and retired from competitive sport in 1951, continuing to do charitable work for young athletes. As her death was a violent one, the consequence of an armed robbery, her body was autopsied. At this point ‘ambiguous’ sexual features were made public.

The revelation of an Eastern European ‘sex fraud’ came at a sensitive time for international sports, as the Summer Olympics that year had been held, controversially, in Moscow. Despite demands that her medals and accolades should be revoked, the International Olympic Committee (hence: IOC) finally issued a statement saying that Walsh had competed in good faith, and had not broken the rules of the day.10 Nonetheless Walsh has joined Ratjen in the canon of gender frauds, as the poster girl and poster boy for ‘sex cheats’. They occur in almost every historical account, text book of sports medicine, or newspaper article about the latest successful female athlete whose physique has provoked suspicion. Both Walsh and Ratjen fit the conventional narrative about the history of sex testing; one a tool of a fascist regime, the other Eastern European, if not strictly a Communist athlete. In Walsh's case the ‘irony’ of the accusation against the all-American Stephens makes her story irresistible to most authors, whether they’re journalists, historians or scientists.

Of course, neither Walsh nor Ratjen had anything whatsoever to do with the introduction of sex testing. Both their stories were revealed years, in one case nearly thirty years, after they had stopped competing, and neither were made broadly public until after systematic sex testing had already been introduced into international sports. Shortly after the accusation that Stephens was a man her team coach, Avery Brundage, called for more systematic screening of suspicious cases. But when he chose to point the finger at ‘suspicious’ cases, it was neither Ratjen nor Walsh that he named. Instead Brundage named the Czechoslovakian runner Zdenka Koubkova who had changed sex from female to male (becoming Zdenek Koubek) in 1936, and the British shot putter and javelin thrower Mary/Mark Weston. Ratjen and Walsh's stories have been reinvented to fit narratives about the Cold War and the politicisation of sport; in so doing, the stories of Koubek and Weston have been lost.

The Devonshire Wonder

Mary Louise Edith Weston (b. ∼1906) competed nationally for the Middlesex Ladies’ Athletics Club and internationally with the British Olympic Team earning the nickname ‘the Devonshire Wonder’ due to exceptional performances in the javelin and shot put. Weston took the Women's Amateur Athletic Association shot put title in 1925 and 1928, winning all three throwing events (shot, javelin and discus) in 1929. Weston also won the international women's shot put title in 1934.11 Shortly after this achievement, Mary Weston had ‘a series of operations in Charing Cross hospital’, after which he abandoned competitive sport to take up a career as a masseur, and changed his name to Mark.12

Weston's story gained media attention in the USA as well as the UK, with close coverage in the British Daily Mirror, and special features in North American in Physical Culture and Time. It's noticeable how positive, generally, this coverage is (especially compared to later media treatment of ‘unfeminine’ athletes). The Daily Mirror carefully pointed out that Weston had won the international shot putting title while unaware that he was ‘competing unfairly against other women competitors’ – it was an honest mistake, not a case of fraud.13 Similar sentiments were repeated whenever Weston made the news; in 1938 when he married his long-term best friend Miss Alberta Bray, a ‘shy blonde in her early twenties’, and tragically in 1942 when his older brother Harry (previously known as ‘Hilda’), hung himself after becoming ‘depressed following [his] operations for change of sex’ (see Figure 1).14

A page from an article in Physical Culture about transsexual individuals in sport. Pictured from left to right are Mark Weston and his partner; Mark Weston competing as Mary Weston; and Zdenek Koubek. D.F. Wickets, Can Sex in Humans Be Changed, Physical Culture (January 1937) pp. 16–7 & 83–5. Unsuccessful attempts were made to trace the rights holders to this image. See also note 11.

Zdenek Koubek's story was similar: he had set national records for long jump, high jump and some track events in Czechoslovakia, and a women's world record for the 800 m in 1934, before requesting in 1935 or 36 that the state should recognise him as a man. He retired from sport to pursue a career in cabaret, which took him to the USA, where he was interviewed by Timemagazine which ran two stories relating to sex fraud and the 1936 Berlin Olympics. These articles discussed the fears of ‘worry-ridden Avery Brundage’ who ‘demanded examination for sex ambiguities in all women competitors’.15Brundage was not the only one advocating that segregation in sports needed to be more vigorously policed, and it was suggested at this time that sex tests should become compulsory at the next Olympic Games, due to take place in 1940.

Although the Second World War disrupted the Olympic schedule international sports organisations rapidly took up the suggestion that some legislation on gender ought to be introduced. By 1946 the International Amateur Athletics Federation (hence: IAAF) had introduced a rule requiring female competitors to bring a medical certificate to prove they were eligible to compete (IAAF rule 17 paragraph 3). From 1948 (London), the IOC also required female competitors to comply with the IAAF's requirements.16 So, it is clear that this concern about gender fraud is a phenomenon of the 1930s and ‘40s, and not solely one of the 1950s or ‘60s.

That said, although certificates were required, these were not evidence of a standardized, internationally recognized gender test. Since neither the IOC nor the IAAF actually defined ‘femininity’ the assumption was that the social or cultural definition in any nation was acceptable for sports, and that any nation's judgement could be trusted. It is this that changed in the 1960s.

Standardizing femininity

The dramatic successes of female athletes from the USSR and GDR in the middle decades of the twentieth century certainly caused the sports organisations of the West some concern. That some of these women had physiques which transgressed traditional Western notions of femininity was obvious, and other historians have written about the ways in which appropriate and inappropriate physicality were discussed in the popular media.

Epitomising this trend were Irina (1939–2004) and Tamara (b.1937) Press, sisters from Ukraine who competed in hurdles and pentathlon, and shot put and discuss respectively. The decision of the Press sisters, along with several of their co-competitors, to drop out of international sport coincidental with the introduction of formal sex tests only added fuel to the rumours about their gender. That the sex tests were necessary seemed to be confirmed by the absence of ‘suspicious’ athletes after their introduction. (The fact that two British athletes in the 1960 Rome Olympic team were accused by some newspapers of being men seems rarely to be reported by historians).17

So systematic, at-event, standardized, ‘scientific’ sex tests were introduced in the 1960s because the process of femininity certification by team and family doctors that already existed could no longer be trusted. The first tests took place at the 1966 European Athletics Championship in Budapest, where female athletes were asked to undergo a visual examination of the genitals and secondary sexual features, carried out by a panel of three female doctors.18 Other sports events instigated similar investigations, and a ‘naked parade’ was used at the 1967 Pan-American Games in Winnipeg. Even more invasive approaches were also trialled; at the 1966 Commonwealth Games in Jamaica female athletes were challenged by a manual examination, likened by one athlete to ‘a grope’.19Unsurprisingly, these tests were deeply unpopular with many athletes, who saw them as invasive, and often functionless or unfair – as the American shot putter Maren Sidler said of the tests in Winnepeg:

The test the IOC chose was the Barr Body test, which involves screening cells taken from the inside of the cheek (a buccal smear). Barr Bodies are cellular artefacts that are easily stained and visualised under a microscope, and a positive test was taken – for the purposes of sports sex testing – to indicate that a cell's sex chromosome complement is XX rather than XY. The Barr Body itself is an inactivated X chromosome; since only one X chromosome is necessary for biological function (otherwise XY human beings would be fatally compromised) the ‘spare’ chromosome folds in on itself forming a dense chromatin body. As critics, both at the time and subsequently, have pointed out, this test for chromosomal sex does not necessarily map on to physiological or phenotypic sex, which are the only kinds of sexual identity that confer a sporting advantage (and there are many confounding conditions, as people can be born with just one or three or more sex chromosomes, so that combinations like XXY or XO are quite possible).23

Nonetheless this was the test used at the Olympic Games through the 1970s and into the 1980s, and although thousands of athletes were tested, none were (officially) reported to have failed after 1968. This low detection rate may, of course, be due to the fact that home nations could easily test their athletes themselves – in the UK the British Association of Sport and (Exercise) Medicine made a ‘sex test’ and a ‘chromatin count service’, available to British governing bodies of sport in 1970.24

In the mid-1980s the high profile case of Spanish hurdler Maria Martinez-Patino, who fought a three-year campaign for reinstatement after being disqualified, was used to pressure the IOC and other organisations into changing (or eliminating) their sex tests. Patino failed a Barr Body test at the World University Games held in Kobe, Japan, in 1985, and was instructed by her coach to retire from sport with an ‘injury’; she refused to do so, and when she started competing in Spain again she was formally disqualified and had her medals and records revoked.25Patino eventually succeeded in overturning the ruling, based on the principle that a specific medical condition (androgen insensitivity syndrome) meant that she ‘failed’ a Barr body test, while gaining no physiological sporting advantage – so the argument was not that testing for sex was problematic in and of itself, but rather than this specific test, using chromosomes as a proxy for sporting ability, was inappropriate. This successful appeal was almost certainly due to the fact that human rights activists and geneticists who did not believe the test was fair took up her cause as a test case through which they could make their points about equality, scientific objectivity, and the complexity of human gender identity (see Figure 2).

The IAAF was the first to drop the sex testing requirement for international competitions (somewhat ironically, as it was also the first organisation to introduce femininity checks via its requirement for certificates in the 1940s, as discussed above). In 1988 it dropped chromosomal and genetic testing in favour of a manual/visual ‘health check’ by the team doctor, and then abandoned all forms of systematic sex testing in 1992. The IAAF argued that these were no longer necessary because doping regulations required athletes to pass urine in front of witnesses, and that modern sportswear was now so revealing that it seemed unfeasible that a man could masquerade as a woman.

The IOC was more resistant to change, instead introducing a new sort of test in 1992, a genetic test which identifies a specific region of code usually found on the Y chromosome and known as the ‘sex determining region Y’. It was considered that the presence or absence of this single gene (which in turn controls the expression of another gene that codes for a protein vital to testicular formation) was a better marker of gender than the presence of X or Y chromosomes.26 Even this test continued to throw what, for the purposes of sex segregation, seem to have been false positives, as although in Atlanta in 1996 eight women ‘failed’ this test all were allowed to compete after further examinations were carried out.

Finally, in 1999 the IOC agreed to follow the IAAF and remove the requirement for blanket sex testing, so that the Millennium Games in Sydney, 2000, were the first Games in three decades where the genetic make-up of female athletes were not scrutinised. Of course, as we have seen recently in the case of Caster Semenya, if the gender of an athlete is actually challenged, she can still be required to undergo a full gamut of tests: physiological, genetic, hormonal, psychological.

Ratjen revisited: reinventing gender fraud

For nearly a year, from her success in the 800 m at the World Championships in Athletics, August 2009, to the final declaration of her femininity from the IAAF in July 2010, the story of Caster Semenya has provoked journalists and academics to explore the history of sex testing in international sports. In the process these stories have helped to consolidate a mythology of gender fraud, which has not been shaken even by the revelation of new archive materials. In fact, this coverage has led to what I believe is a brand new myth about gender fraud, this time reinventing Stella Walsh as a ‘suspect’ athlete in the 1930s, when in fact her femininity was (comparatively) unproblematic until her death in 1980.

Gender is an extraordinarily difficult topic for historical analysis; it is an intrinsically embodied, lived experience which we can find hard to reconstruct, and it is also a personal and private matter which is often deliberately concealed from official records, both medical and sporting. By relying instead on a closed ‘canon’ of publically available information, often newspaper reports and early articles about sex testing, writers, including historians (and including myself), have restated and reinforced stories about gender fraud which are not based on first-hand primary material or archive research. Originally, and most obviously, the strong association between the tensions of the Cold War and sex testing has obscured the stories of earlier transsexual athletes which do not fit the pattern of post-war gender ‘frauds’.

But more worryingly, as some stories have been lost, others have explicitly been reinvented or re-imagined to fit this Cold War storyline. Stella Walsh's story is such a case, and is one that is currently in the active process of being re-created to fit with the narrative of gender testing which starts with the ‘Press Brothers’, and in which gender frauds are explicitly ‘other’ to the white western world: communist, fascist, Black. Walsh's reinvention started at least as early as the 1990s, as the following quote, from a paper in the Journal of the Medical Association of Georgia demonstrates:

More recently the case has been explicitly made that Walsh was a suspected fraud as early as the 1930s. In its obituary of Irina Press on 31 May 2004, the UK newspaper the Telegraphclaimed that Walsh was one of the athletes who, like the Press sisters, had incited speculation about gender. Suggesting that Walsh was ‘a man’ the paper claims that before the Press sisters retired from sport

A recent article in the South African Journal of Sports Medicine repeats the suggestion that Walsh's gender was a subject of public questioning in the 1930s, and claims that newspapers referred to her as ‘Stella the Fella’.29The reference for this claim is an article in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, which does not in turn give a source for its belief that not only was Walsh's gender suspect and that she generated ‘Stella the Fella’ headlines, but also that it was actually Walsh who personally challenged Stephen's eligibility in 1936 (most earlier accounts have a Polish journalist as the accuser).30 The claim that there were contemporary ‘Stella the Fella’ headlines is even repeated in sociology texts.31 But such reports of specific, printed suspicions about Walsh's gender in the 1930s would seem to have appeared in articles only since 2004, i.e. after the claim was made in the Telegraph obituary.

It is of course possible that Walsh's gender was questioned in some circles, and her manly physique was certainly noted in newspaper articles. But Helen Stephen's strapping figure was also commented on, and the bodies of two British athletes were athletic enough to have them accused of being men in 1960 (see above); there are dozens (probably hundreds) of other cases where the successful, physically powerful woman athlete has been subject to suspicions, rumour and innuendo. If we selectively remember only rumours that were ‘revealed to be right’, suspicion would appear a disproportionately powerful predictor of gender ambiguity. This is a dangerous ‘lesson from history’ if it is to be applied to female athletes today.

Even more recent, however, is the revisitation of Heinrich Ratjen (still often called ‘Hermann’). Ratjen, after all, is the archetypal story of gender fraud – to date in fact the only ‘genuine’ case of a man masquerading as a woman. The movie, Berlin 36, which was released in Germany in the Autumn of 2009 dramatises Ratjen's case, using the pseudonym ‘Marie Ketteler’ in order tell the story of another excluded athlete, Gretel Bergmann. Bergmann was a Jewish athlete, and her exclusion from the German Olympic team (ostensibly on grounds of underperformance) was almost certainly because of her ethnicity. She was replaced by Ratjen, which again fulfils a neat narrative of the totally corrupt, transgressive fascist body and sport (see Figures 3 and 4).

Heinrich Ratjen competing as ‘Dora’ at a track and field event in Berlin in 1937. Bild-183C10336. Reproduced with permission from the The Digital Picture Archive of the Press- and Information Office of the [German] Federal Government: http://www.bundesbildstelle.de/.

Heinrich Ratjen and another high-jump team member, Elfriede Kaun, in 1937. Bild-183C10336: Reproduced with permission from the The Digital Picture Archive of the Press- and Information Office of the [German] Federal Government: http://www.bundesbildstelle.de/.

But in response to the film, an investigative journalist from Der Spiegelpursued the question of Ratjen's gender, and retrieved original material from the Department for Sexual Medicine at Kiel University Hospital, which reinterprets Ratjen's story in a way entirely consistent with contemporary gender controversies, and which undermines our typical story of fascist/communist transgression.

According to these records, Ratjen's gender ambiguity was not discovered at a sporting event, or revealed to a journalist in the 1950s, but was due to an ID-card challenge made by a German police officer at a train station. While Ratjen's identity card said he was female, the police officer believed him to be male; a medical examination declared him a man. Although the Reich Sports Ministry objected, and requested further tests and a stay in a sanatorium, eventually Ratjen was accepted as a man, officially re-designated, and given a new name and papers. Ratjen's circumstances appear to have been a consequence of confusion shortly after his birth, which neither he nor his parents seemed able to rectify when his identity became conflicted during adolescence, after a childhood raised unquestioningly as a girl. Ratjen was after all only 17 in 1936 when asked to compete for the Fatherland. Although the story of deliberate Nazi fraud makes better headlines, Ratjen's story is probably a more homely and familiar one of medical error, gender uncertainty, and embarrassed silences.32

Reconstructing gender

There is a difference between history and the uses of history. Without doubt the media coverage of gender frauds has laid them into particular narrative patterns.

They are often stories of direct conflicts between good and evil, the wonders of modern science in a battle against frauds, or the dangers of a medicalised, over-competitive sports ideology where even gender identity and sexual health can be sacrificed in the cause of national sporting success. There is considerable slippage between anti-drug rhetoric and discussions of sex testing – indeed, in some cases there is clear confusion between the androgenisation caused by steroids and conditions which might cause a woman to fail a sex test (it is unlikely that any sex test, now or in the past, would fail a competitor merely for the side-effects of steroid use). However, in most sources in the popular media, and many in the medical and scientific press, there is little critique of the fundamental concept that there are two types of athlete – and only two types – who can in theory be objectively, scientifically distinguished. (The question of whether genders, even if they exist, should be distinguished, or whether other measures would better ensure fairness in sport is usually left to academic work in philosophy and sociology.) It is therefore also the case that stories of gender fraud can reinforce a range of cultural and social understandings of femininity.

So we need to be careful about how we participate in the reinvention and reimagining of history; while the representational politics of gender testing are worth exploring, there is a risk that unless carefully written, our accounts of the representation of Ratjen or Walsh can be used by other writers to reinvent these historical actors’ stories (e.g. causing a newspaper's printed suspicions to become the lived reality). At the same time, we have clearly under-written other aspects of gender testing. There are very few articles by historians on the development of the technology of sex testing for sports, or on the conscientious objectors, the scientists who refused to take part and who advised and campaigned against the use of tests. There is no account explaining why the IOC chose the Barr Body test in the 1960s, or the sex determining region Y test in the 1990s. There is no thorough explanation for the difference between the IAAF and the IOC in the 1990s (and little to nothing on other sporting organisations’ gender testing).

Finally, we do not have a good account of sex testing and gender uncertainty before the Cold War. Athletes such as Weston are virtually written out of the current story, but need to be understood in their own context – i.e. within the revived fascination with sexual differentiation, hormones, steroids and organ therapy of the 1920s and ‘30s.33

Cultural fears that sport and exercise might be medically dangerous to women are well studied, but when exactly did concerns that exercise might virilise women turn into a fear that being virile and being a woman was ‘cheating’?

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

.

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

.

@oracle

Long article but worth reading.

As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health.

Learn more: |

2010 Dec; 34(4): 157–163.

Abstract

Most international sports organisations work on the premise that human beings come in one of two genders: male or female. Consequently, all athletes, including intersex and transgender individuals, must be assigned to compete in one or other category. Since the 1930s (not, as is popularly suggested, the 1960s) these organisations have relied on scientific and medical professionals to provide an ‘objective’ judgement of an athlete's eligibility to compete in women's national and international sporting events. The changing nature of these judgements reflects a great deal about our cultural, social and national prejudices, while the matter of testing itself has become a site of conflict for feminists and human rights activists. Because of the sensitive nature of this subject, histories of sex testing are difficult to write and research; this has lead to the repetition of inaccurate information and false assertions about gender fraud, particularly in relation to the ‘classic’ cases of Stella Walsh and Heinrich/Hermann/Dora Ratjen. As historians, we need to be extremely careful to differentiate between mythologies and histories.

The athletic girl not unfeminine1

The relationship between femininity and physical exercise is well studied by historians; in fact, it is probably better analysed and certainly more problematised than the relationship between masculinity and sport.2 It comes as no surprise that as major international sporting events were developed in the very late nineteenth century issues of physical display, modesty, muscularity, competition and the perpetual risk of sterility were all used to exclude women from many sporting activities.

Virtually the only way women could participate in competitive sport was through sexually segregated events.

The standard account of this process is as follows: the early years of the twentieth century are generally represented as a period of struggle and triumph for women's sports, with the eventual acceptance of a significant women's programme in the Olympics in 1924 and the proliferation of national organisations for women's sport.3

But as international sport took its place as ‘sublimated war’ at mid-century, the desire to win apparently became so pressing for some nations that deliberate and systematic cheating took place in both the men's and women's events. Consequently, doping and gender fraud became central concerns in the late 1950s and 60s, resulting in the eventual introduction of systematic testing for both at international sporting events in the late 1960s. The usual explanation given for the introduction of sex testing is a list of gender frauds (or suspected frauds) most of whom fulfil a specific stereotype: physically muscular, deep-voiced competitors living under totalitarian, fascist or communist regimes.

Amongst the ‘canon’ of gender frauds are normally the well-built and extremely successful Ukrainian sisters, Irina and Tamara Press, who dropped out of international competition when gender tests were introduced.4 For an earlier example, the usual name listed is Hermann Ratjen, who, we are told, through loyalty to the Hitler Youth, bound his genitals and competed as a woman – Dora Ratjen – at the 1936 Berlin Games. Ratjen may have been discovered as a fraud at a sporting event in the late 1930s, and was definitively revealed by a journalist in the 1950s, to whom he told his story.5Ratjen's case has even been made into a feature-length, award-winning movie.

There are three problems with this account. Firstly, it ignores the fact that systematic sex testing, of a sort, existed at least as early as the 1940s. Secondly it obscures the fact that the first well-known gender ‘frauds’ in international sport were not Nazi sympathisers, or Communist state athletes, but a British shot putter, and a Czechoslovakian runner. Finally, Hermann Ratjen's name was not Hermann, but Heinrich, and documents (including medical records) released after his death in 2008 suggest that rather than being a conspiracy, his place on the 1936 German women's high-jump team is explained by a more mundane and human case of gender uncertainty, medical error, fear and embarrassment.

The story of sex testing, and histories of sex testing, in international sport tell us a great deal about social attitudes to gender, and how the co-option of science in sport (however it is resisted by scientists and human rights campaigners) can act to essentialize social categories.6 Sex testing, after all, is a tautological (or at least circular) process: the activities which we recognise as sports are overwhelmingly those which favour a physiology which we consider ‘masculine’. As a general rule, the competitor who is taller, has a higher muscle-to-fat ratio, and the larger heart and lungs (plus some other cardio-respiratory factors) will have the sporting advantage. It is therefore inevitable that any woman who is good at sport will tend to demonstrate a more ‘masculine’ physique than women who are not good at sport. What the sex test effectively does, therefore, is provide an upper limit for women's sporting performance; there is a point at which your masculine-style body is declared ‘too masculine’, and you are disqualified, regardless of your personal gender identity.

For men there is no equivalent upper physiological limit – no kind of genetic, or hormonal, or physiological advantage is tested for, even if these would give a ‘super masculine’ athlete a distinct advantage over the merely very athletic ‘normal’ male. (Of course, both men and women are liable to the same testing regimes when it comes to external sources of advantage, i.e. doping.) There are probably hundreds of genetic variations which lead to ‘unfair’ advantages in sport; only those associated with gender are used to exclude or disqualify athletes.

This article will explore how this unequal situation came about, and discuss in brief the various technologies of gender and sex testing in sports. ‘Gender’, ‘sex’ and ‘femininity’ are often used interchangeably when referring to testing in sports despite having quite different meanings; in this article I will quote directly from the primary sources or use the phrase ‘sex testing’.7 More importantly I will also attempt to disrupt the comfortable narratives we have in place of sex-frauds being over-competitive athletes from non-democratic regimes.8

The canon of gender frauds

There is a straightforward narrative path through the history of gender testing, which takes as its earliest starting point the Berlin Olympics of 1936. This is where Ratjen competed as a woman in the high-jump, but our attention is more often directed at the 100 m race. Here the American runner Helen Stephens (the ‘Fulton Flash’) was accused of being a man when she narrowly beat the favourite, Polish runner Stanisława Walasiewicz. Stephens underwent an unspecified test and was declared a woman by the Berlin authorities, taking gold.9 Nearly four and a half decades later, in 1980, Walasiewicz (now known by her Anglicized name, Stella Walsh, which will be used through the rest of this article) was shot dead in a department store car park in Ohio. She had emigrated to the USA in 1947, and retired from competitive sport in 1951, continuing to do charitable work for young athletes. As her death was a violent one, the consequence of an armed robbery, her body was autopsied. At this point ‘ambiguous’ sexual features were made public.

The revelation of an Eastern European ‘sex fraud’ came at a sensitive time for international sports, as the Summer Olympics that year had been held, controversially, in Moscow. Despite demands that her medals and accolades should be revoked, the International Olympic Committee (hence: IOC) finally issued a statement saying that Walsh had competed in good faith, and had not broken the rules of the day.10 Nonetheless Walsh has joined Ratjen in the canon of gender frauds, as the poster girl and poster boy for ‘sex cheats’. They occur in almost every historical account, text book of sports medicine, or newspaper article about the latest successful female athlete whose physique has provoked suspicion. Both Walsh and Ratjen fit the conventional narrative about the history of sex testing; one a tool of a fascist regime, the other Eastern European, if not strictly a Communist athlete. In Walsh's case the ‘irony’ of the accusation against the all-American Stephens makes her story irresistible to most authors, whether they’re journalists, historians or scientists.

Of course, neither Walsh nor Ratjen had anything whatsoever to do with the introduction of sex testing. Both their stories were revealed years, in one case nearly thirty years, after they had stopped competing, and neither were made broadly public until after systematic sex testing had already been introduced into international sports. Shortly after the accusation that Stephens was a man her team coach, Avery Brundage, called for more systematic screening of suspicious cases. But when he chose to point the finger at ‘suspicious’ cases, it was neither Ratjen nor Walsh that he named. Instead Brundage named the Czechoslovakian runner Zdenka Koubkova who had changed sex from female to male (becoming Zdenek Koubek) in 1936, and the British shot putter and javelin thrower Mary/Mark Weston. Ratjen and Walsh's stories have been reinvented to fit narratives about the Cold War and the politicisation of sport; in so doing, the stories of Koubek and Weston have been lost.

The Devonshire Wonder

Mary Louise Edith Weston (b. ∼1906) competed nationally for the Middlesex Ladies’ Athletics Club and internationally with the British Olympic Team earning the nickname ‘the Devonshire Wonder’ due to exceptional performances in the javelin and shot put. Weston took the Women's Amateur Athletic Association shot put title in 1925 and 1928, winning all three throwing events (shot, javelin and discus) in 1929. Weston also won the international women's shot put title in 1934.11 Shortly after this achievement, Mary Weston had ‘a series of operations in Charing Cross hospital’, after which he abandoned competitive sport to take up a career as a masseur, and changed his name to Mark.12

Weston's story gained media attention in the USA as well as the UK, with close coverage in the British Daily Mirror, and special features in North American in Physical Culture and Time. It's noticeable how positive, generally, this coverage is (especially compared to later media treatment of ‘unfeminine’ athletes). The Daily Mirror carefully pointed out that Weston had won the international shot putting title while unaware that he was ‘competing unfairly against other women competitors’ – it was an honest mistake, not a case of fraud.13 Similar sentiments were repeated whenever Weston made the news; in 1938 when he married his long-term best friend Miss Alberta Bray, a ‘shy blonde in her early twenties’, and tragically in 1942 when his older brother Harry (previously known as ‘Hilda’), hung himself after becoming ‘depressed following [his] operations for change of sex’ (see Figure 1).14

A page from an article in Physical Culture about transsexual individuals in sport. Pictured from left to right are Mark Weston and his partner; Mark Weston competing as Mary Weston; and Zdenek Koubek. D.F. Wickets, Can Sex in Humans Be Changed, Physical Culture (January 1937) pp. 16–7 & 83–5. Unsuccessful attempts were made to trace the rights holders to this image. See also note 11.

Zdenek Koubek's story was similar: he had set national records for long jump, high jump and some track events in Czechoslovakia, and a women's world record for the 800 m in 1934, before requesting in 1935 or 36 that the state should recognise him as a man. He retired from sport to pursue a career in cabaret, which took him to the USA, where he was interviewed by Timemagazine which ran two stories relating to sex fraud and the 1936 Berlin Olympics. These articles discussed the fears of ‘worry-ridden Avery Brundage’ who ‘demanded examination for sex ambiguities in all women competitors’.15Brundage was not the only one advocating that segregation in sports needed to be more vigorously policed, and it was suggested at this time that sex tests should become compulsory at the next Olympic Games, due to take place in 1940.

Although the Second World War disrupted the Olympic schedule international sports organisations rapidly took up the suggestion that some legislation on gender ought to be introduced. By 1946 the International Amateur Athletics Federation (hence: IAAF) had introduced a rule requiring female competitors to bring a medical certificate to prove they were eligible to compete (IAAF rule 17 paragraph 3). From 1948 (London), the IOC also required female competitors to comply with the IAAF's requirements.16 So, it is clear that this concern about gender fraud is a phenomenon of the 1930s and ‘40s, and not solely one of the 1950s or ‘60s.

That said, although certificates were required, these were not evidence of a standardized, internationally recognized gender test. Since neither the IOC nor the IAAF actually defined ‘femininity’ the assumption was that the social or cultural definition in any nation was acceptable for sports, and that any nation's judgement could be trusted. It is this that changed in the 1960s.

Standardizing femininity