The no-good, the bad and the ugly.So you start a thread that links to a 'nobody' and his 'nobody opinion' and then you go all haywire trying to defend his/your nobody's opinion.

Talk about no good, for nothing nobody thread.

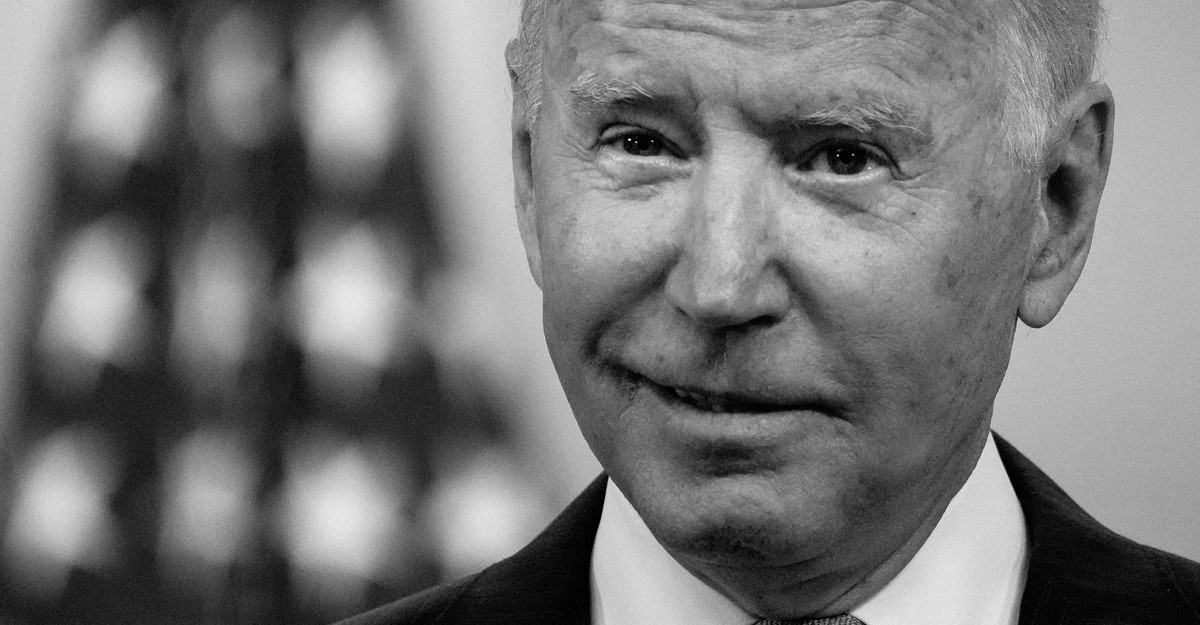

Is Joe Biden after 10 months: Worst president ever?

- Thread starter |2 /-\ | /|/

- Start date

Which of the Nazis talked about if you tell a lie often enough?In the spirit of non-partisanship objectivity so eloquently noted above and also as stated above,

"What we can say is" ..... the above post is the "worst ever" on this topic, a "total train wreck" and "certainly one of the worst posters on this topic in living memory".

And dat my friend, is as you so plaintively stated is "the problem."

the loonie left manual states"In the spirit of non-partisanship objectivity so eloquently noted above and also as stated above,

"What we can say is" ..... the above post is the "worst ever" on this topic, a "total train wreck" and "certainly one of the worst posters on this topic in living memory".

And dat my friend, is as you so plaintively stated is "the problem."

rule # 2a subsection 4, paragraph 0.01

when you have no logical argument to make, opt to attack the character of the messenger. :i.e. shut them down, platform them , silence the opposition

Last edited:

Passed COVID relief, passed infrastructure (this is in a broader sense).What has he done to create unity and bring people together since he started office?

Outside of that he has depoliticized the Department of Justice and various other offices.

He returned government functioning to a more normal position that was less straight-up cronyism.

He's cast his rhetoric primarily as that of someone who is president of the whole country and not just responsible to his own voters and supporters.

He didn't do a complete purge of Trump's appointees but followed standard procedure.

He's done a lot.

But there is only so much you can do when the other side views anything other than complete capitulation to them as "being divisive".

Doesn't help that the media is mostly against unity because divisive is better for ratings.

From a Canadian perspective; Joe canceled the pipeline which is bad, he resolved the Meng situation which is good, and we are flush with US-made vaccines which is great.

To this day it boggles my mind how well we did in terms of getting vaccinated for a country that can not produce its own vaccine. Biden took care of US allies with the vaccine and he recognizes that Canada is an ally. Maybe if Trump was still president he would have done the same or even done more for Canada, but most likely he would have done less.

To this day it boggles my mind how well we did in terms of getting vaccinated for a country that can not produce its own vaccine. Biden took care of US allies with the vaccine and he recognizes that Canada is an ally. Maybe if Trump was still president he would have done the same or even done more for Canada, but most likely he would have done less.

either Adolf Hitler or the airhead Catherine McKenna - you know the same climate Barbie who has been spreading "climate emergency" propaganda, and who lost billions of tax payers moneyWhich of the Nazis talked about if you tell a lie often enough?

pick which ever Nazi works for you

Passed COVID relief, passed infrastructure (this is in a broader sense).

Outside of that he has depoliticized the Department of Justice and various other offices.

He returned government functioning to a more normal position that was less straight-up cronyism.

He's cast his rhetoric primarily as that of someone who is president of the whole country and not just responsible to his own voters and supporters.

He didn't do a complete purge of Trump's appointees but followed standard procedure.

He's done a lot.

But there is only so much you can do when the other side views anything other than complete capitulation to them as "being divisive".

Doesn't help that the media is mostly against unity because divisive is better for ratings.

oh no. you are quite mistaken

it is not how the other side views it , rather how the electorate / the general public views it

That is not going well at all for sleepy joe

at least you offered up something part way tangible this time, rather than just attack the posters character

Goebbels described the big lie in an article he wrote in 1941, “Churchill’s Lie Factory,” where he wrote:

"The English follow the principle that when one lies, one should lie big, and stick to it. They keep up their lies, even at the risk of looking ridiculous."

"The English follow the principle that when one lies, one should lie big, and stick to it. They keep up their lies, even at the risk of looking ridiculous."

Six Theories of Joe Biden’s Crumbling Popularity

The president’s approval ratings keep falling. The question is why.

Six Theories of Joe Biden’s Crumbling Popularity

The president’s approval ratings keep falling. The question is why.

The biggest mystery in American politics right now—and perhaps the most consequential one—is how Joe Biden became so unpopular.

Biden began his presidency moderately popular: At the start, Quinnipiac University’s polling found that 53 percent of Americans approved of him and 36 percent did not. Today’s numbers are the mirror image: In a Quinnipiac poll released yesterday, 36 percent approve, while 53 percent disapprove. FiveThirtyEight’s average of polls finds him doing slightly better—42.8 to 51.7—but still in a consistent slide since the end of July. The numbers are very polarized, but Republicans have always disapproved strongly of Biden; the big difference here is erosion among Democrats and independents.

This reversal could have wide-ranging effects. Biden still hopes to pass a massive social-spending program, for which he needs uniform Democratic support. Depending on their understanding of the causes for the slide, members of Congress might defect. Biden’s unpopularity may already have cost Democrats the Virginia governorshipand nearly sunk Governor Phil Murphy of New Jersey too. If Biden is this unpopular in a year, congressional Democrats will be entirely swamped in the midterms.

But although the effects are evident, the causes are not. Even in today’s era of heavily quantified politics, some enigmas remain. Here are a few of the theories in play for why the president keeps losing ground, as well as their flaws.

Simple Gravity

Familiarity, like politics, breeds contempt. Combine the two and you get a toxic result. Although nearly every president (Donald Trump is a notable exception) takes office with good feelings and some approval from the public, they also almost always lose it soon. Campaign promises hit the rough reality of governance, voters forget the happy vibes of the campaign, and they sour on the guy they elected. In recent times, Americans tend to just hate whoever’s in power. If you think Biden’s numbers are bad, look at how Congress is doing, according to Quinnipiac: Democrats are at 31–59, and Republicans are at an even worse 25–62.

This theory is undoubtedly true, but it doesn’t seem to account for all the facets of the Biden slide. In particular, it doesn’t explain what happened in August, when Biden’s numbers flipped and his approval went underwater.

Afghanistan

That inversion happened just as the Biden administration was fumbling the withdrawal from Afghanistan. At the time, many tempered observers (including me) guessed that although the withdrawal might be a tactical or moral catastrophe, it would not be a political one—or at least not an enduring political one. Big events like the withdrawal, which drew extensive media coverage, can temporarily depress a president’s standing, but this one seemed unlikely to endure. First, voters don’t really tend to weight foreign policy heavily in their assessments; second, majorities of Americans had supported leaving Afghanistan for years, Trump among them.

Read: When bipartisanship risks undermining democracy

With nearly three months’ perspective, we appear to have been wrong. Biden’s numbers never recovered, and have continued to slide—even though Afghanistan has largely disappeared from the headlines once more. Perhaps the effects endured because the withdrawal called Biden’s competence—one of his core campaign selling points—into question, and because the debacle encouraged a general pessimism about the country’s standing overall.

COVID

Something else happened right around the time of the Afghanistan withdrawal: COVID staged a distressing comeback, even though vaccines had become widely available. The summer had seemed to be a moment of freedom, but then it became clear that the disease hadn’t gone away. Biden’s approval on COVID handling in an NBC News poll, as high as 69 percent in April, fell to 53 percent. What exactly that means is a little unclear. Some disapproval could be from liberal COVID hawks upset that the disease was on the rise; some could be from conservative doves annoyed about vaccine mandates and other lingering measures. Either way, it seems to have dragged Biden down.

David A. Graham: The right’s total loss of proportion

During the campaign, Biden promised to do better than Trump on COVID. His ability to connect to voters through grief seemed matched to the moment, but that moment seems over. The national COVID toll recently passed 750,000 and was met with a shrug. Voters don’t want consolation—they want normalcy, and delivering that is likely beyond the ability of any president. Anger about schools being closed for long stretches of the pandemic seems to have been a major factor in Republican victories in Virginia this month. Since August, COVID has waned—by the end of September, the liberal pollster Navigator found that the portion of Americans who thought the worst of the pandemic was yet to come was shrinking fast—and is now waxing again. Biden’s approval has kept sliding through the waves.

Inflation, Especially Gas Prices

COVID continues to ail the economy too—especially in the form of inflation. By many measures, Americans are better off than they have been in some time (though of course averages elide uneven distribution of gains), and employment is growing quickly. Yet opinions on the economy remain negative. A likely culprit is inflation, which is devouring wage increases. Supply-chain problems, shifts in demand, and the effects of major government stimulus earlier this year all feed rising prices. Biden’s credibility here is also hobbled by the fact that he and his advisers promised that any inflation would be ephemeral, but it has stuck around.

Some progressives have argued, citing historical evidence, that the public’s bleak views of inflation are almost entirely a factor of gas prices. Almost all Americans have to buy gas regularly, and the prices are advertised in large font or LED lights on the street, making rising costs for each gallon very visible. The left-wing firm Data for Progress contends that while the Afghanistan withdrawal hurt Biden, controlling for it produces a clean relationship between gas prices and Biden approval, though it’s not clear whether causation exists here or merely correlation.

Democrats in Disarray

Biden’s campaign was all about likability and light on policy, which makes the current situation all the more unusual: Biden is unpopular, while his policies are in vogue. That’s inconvenient for critics who say the problem is that liberal Democrats have overreached, but it still presents a conundrum of why a president with such well-liked ideas is so disliked. Part of the blame has to fall on the nightmarish process by which his party is attempting to enact those policies. Democrats have been at war with one another for months in Washington, and even if voters like the results, the spectacle is deeply unpleasant. You can’t turn on a cable-news channel these days without hearing a Democrat explaining why his or her least-favorite part of the Biden agenda is bad, which may be more persuasive than the predictable parade of Republicans saying the same thing.

If that’s true, it helps explain why Biden’s slide has been particularly driven by eroding support among Democrats and independents. Disaffection could entail several different, conflicting impulses. Some Democrats are upset that the party hasn’t moved fast enough, others that it hasn’t prioritized their personal preferences, and still others that it’s pursuing ideas they dislike. The end result is the same: The party’s a mess, and people who voted for it are annoyed.

Know Your Enemy

One way to keep restive Dems in the fold is to give them something to be opposed to—and that’s sorely missing for Biden. From about two weeks into his presidency, Trump’s approval was low and his disapproval high, but those numbers remained largely stable. That’s because unlike Biden, Trump was good at keeping his base riled up. He always gave them someone to be angry at. Biden isn’t a rabble-rouser, though the same dynamic helped him in 2020. When he was least visible, he was most popular, and many Democrats said they were more energized to beat Trump than elect Biden.

This is an age of affective partisanship, where politics is driven to a dangerous degree by antipathy for the other team. But Biden doesn’t have a convenient villain now. Democrats tried to make the Virginia gubernatorial race about Trump but still lost. Republicans, now on the margins, feel persecuted and riled up, but when a party controls the White House, House, and Senate, its supporters tend to get complacent. If Biden doesn’t turn around his approval quickly, Democrats will soon have plenty of opportunities to feel their own sense of disaster and persecution, though by then, that will be small consolation.

It is impossible to unite people that refuse to be united...I am not interested in that. It’s unfortunate that many people keep taking Biden criticism personal and can’t defend their point objectively without being personal. I feel that he is a bad president and am free to express my opinions.

Its disappointing that he is not serving the American people like he promised and creating divisions instead of unity like he promised.

Eventually the bad decisions and governance there could spill over here.

It’s also a good discussion to learn not what to do in this role.

I don’t think he is a good president and don’t think he represents the people’s best interest as a collective. The approval rating are presently showing this.

This is not helping either...Biden should be condemning this stuff and speaking out against it.It is impossible to unite people that refuse to be united...

Illinois Dem blasted for calling Wisconsin Christmas rampage ‘karma’

Mary Lemanski, a social media director for the Democratic Party in DuPage County, began her heartless online tirade by snarkily dismissing the tragedy as “just self-defense.”

Illinois Dem blasted for calling Wisconsin Christmas rampage ‘karma’

Started a war that killed over 700,000 Americans and had no post-war plan.Um, no he isn't the worst. We have one that oversaw the actual breaking up of the union.

You think he needs to condemn it because people are confused that he might approve of it?This is not helping either...Biden should be condemning this stuff and speaking out against it.

View attachment 102796

“

Illinois Dem blasted for calling Wisconsin Christmas rampage ‘karma’

Mary Lemanski, a social media director for the Democratic Party in DuPage County, began her heartless online tirade by snarkily dismissing the tragedy as “just self-defense.”nypost.com

Illinois Dem blasted for calling Wisconsin Christmas rampage ‘karma’

The person is a professional member representing the democrats in that area. You know an official public representative.You think he needs to condemn it because people are confused that he might approve of it?

Rittenhouse acquittal tightens the political vise for Biden

A difficult political atmosphere for President Joe Biden may have become even more treacherous after the acquittal of Kyle Rittenhouse